Karen Edler was a recently transferred college student at Dickinson College when the Three Mile Island Incident occurred on March 28, 1979. Although the American Yawp Textbook mentions that Jimmy Carter was “a nuclear physicist and peanut farmer who represented the rising generation of younger, racially liberal “New South” Democrats,” it does little to display his expertise on nuclear energy when considering the Three Mile Island Incident of 1979, failing to mention the man-made catastrophes of the decade. [1] Edler’s story serves to fulfill its gaps, giving historical context to the crisis that sparked the debate over nuclear energy from the late 1970s to the present day.

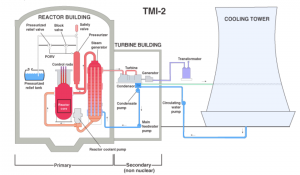

Thursday, March 28, 1979, marked the first day of the crisis. According to Dickinson College archives, at 4:00 am, “a false valve went open unnoticed and allowed thousands of gallons of coolant water to flow from one of the plant’s reactors.[2] This caused temperatures within the unit (Reactor 2) to rise to over 5000 degrees, causing the fuel core to begin to melt.”[3] As conflicting information by the Metropolitan Edison utilities and plant officials ran rampant, Edler recounts the lack of information concerning the Three Mile Incident when it occurred. “I think it took at least a day for it to spread around campus. When you were in class, professors would briefly mention it, but we didn’t have a lot of information about exactly what happened or how it would affect us.”[4] Edler reflected how many Dickinson students had little understanding of the direness of the situation or the existence of the plant itself. “I knew that there was some kind of a plant. I did not know it harnessed nuclear energy at the time. It was clear since we used to see it when my parents drove me to or from Dickinson because of the huge stacks and the smoke coming out from them.”[5] It would lead to a score of confusion within the student body, as many awaited the response of the college president and local governmental officials.

Edler recounts Dickinson’s response to the crisis on the following day of the incident. “Dickinson asked us to voluntarily leave campus if possible on the first weekend after three-mile island. They asked people to leave by that Friday because they were going to be an evacuation center. No one was quite sure when these things were going to happen or how international students would be affected.” [6] She also mentions that “the school didn’t shut down until the end of that weekend. Still, college President Samuel Banks decided to close the college for a full week.” [7] She notes how the swift action of the college reflected the growing concerns of parents at the time, who had been listening to the conflicting reports of the situation in both the local and national media. The power of television in adding to nuclear hysteria was also clear in the student body. “It was common to see students in their respective dorms gathered around a single silver screen. It brought fast information on the rising crisis, especially through the local ABC Action News 27.” [8] Newspaper articles like the Dickinsonian further disseminated the details of the crisis in the days following. Reflecting on the heightened emotions on campus in the face of a rising student exodus, “parental inquiries flooded the College switchboard, necessitating that it remains open round the clock throughout the weekend,” as a United Telephone Company shift supervisor reported that “it’s a mess.” [9]

The rising crisis at Three Mile Island soon enveloped the White House and the national media. According to the American Experience site at PBS, President Jimmy Carter ordered that “phone lines be connected between the White House, the NRC, and the State House at Harrisburg” with Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburgh.[10] A former nuclear engineer for the Navy, Carter inspected the embattled plant on April 1, 1979. In a show of presidential support for Pennsylvanians and the surrounding Harrisburg area, Carter’s visit gave a “much-needed morale boost,” according to former Mayor Robert Reid of Middletown, Pennsylvania.” People weren’t talking to one another. They were cooped up in their homes, and when he came, it seemed like everyone came out to see the president, and it was really a shot in the arm.” [11] The wave of optimism Carter brought to the growing crisis reflected a change in tone from the national media, as the highly influential CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite stressed that the incident was “a “horror” that “could get much worse.” [12]

CBS News coverage of the crisis

The ongoing effects of the Three Mile Island Incident met that Dickinson College would have to serve a more significant role in the Cumberland and Dauphin County area. Edler reflects how Dickinson College would serve as an evacuation site and a command center on the crisis for the local area. “I understood that Dickinson was going to be used for evacuated residents of a nursing home and for a staging area for what we would call first responders today, fire companies, and others that were there to assist” as “It was a time of real uncertainty, and no one really understood what would happen exactly.”[13] According to the Three Mile Island archives at Dickinson College, “physicists on campus, including John Luetzelschwab and Priscilla Laws, brought together a student group to

monitor radiation levels, and found that there was no detectable radiation from the TMI accident in the Carlisle,” advising “local emergency management authorities on radiation monitoring and safety.[14]” Edler notes that “I did not learn later that Dickinson used some of the professors and international students who could not leave campus at the time to interview and create archives of information about people’s experiences surrounding the incident,” but pointed to the role of the WDCV radio station amid the crisis.[15] According to an article by the Dickinsonian on April 12, 1979, the “WDCV provided special news shows every hour and released statements from the college. The station also provided the community with reports from the Physics department, and broadcast live the informational meetings that were held evenings.”[16] The WDCV broadcastings that would spark a debate on nuclear energy when students returned to campus reflected a national anti-nuclear energy movement that was quickly rising.

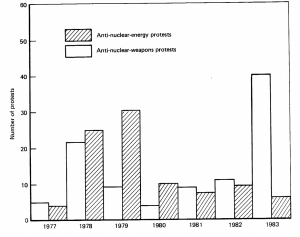

The Three Mile Island Incident made many Americans aware of the dangers of nuclear energy, leading to the explosion of anti-nuclear energy movements across the country. In a comparing anti-nuclear energy and anti-nuclear weapons protests, anti-nuclear energy protests rose from 25 protests in 1978 to around 32 protests in 1979 after the Three Mile Incident, a 28% increase.[17] Anti-nuclear energy movements found solace on college campuses like Dickinson. Edler portrays, “There were definitely more people on campus who became more interested in the anti-nuclear movement, as the accident at Three-Mile Island really kicked conversations about the safety of nuclear energy into gear. Many people were worried, predicting there could be another nuclear accident in the future that could affect even more people in the country.”[18] Edler remembers her own uneasiness returning to campus, reflecting on the mood of the student body at the time. “I remember my mother driving along the Pennsylvania Turnpike when we returned to Dickinson College the following week, and you could still see quite an ominous cloud over the three-mile island. It left me with a sense of uneasiness initially, as I gauged my trust with local authorities who felt they contained the situation.”[19]

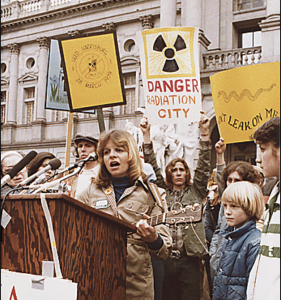

In the immediate aftermath of the Three Mile Island Incident, there was an anti-nuclear energy protest in Harrisburg on April 8, 1979, that called for the plant’s closure. Only “1,000 people marched on the Pennsylvania State Capitol to protest the weekend after the crisis.”[20] However, according to student Jenny Jordan of The Dickinsonian, “3000 people showed up for a rally in Groton, Connecticut and 5000 showed up for one in San Francisco. In Germany, demonstrators yelled, “We all live in Pennsylvania.”[21]According to the Atlanta Constitution, it foreshadows the “largest anti-nuclear-energy crowd to assemble in the United States – upwards of 70,000 by official estimates” on May 7, 1979.[22] Demonstrators marched on the Capitol building to “protest the nation’s growing dependence on nuclear energy,” chanting “No more nukes- No more Harrisburgs.”[23] Many began to realize the long-term health and environmental effects of the incident on the Harrisburg area.

According to the York Daily Record, in 1980, it “may be 12-15 years” before the TMI cleanup happens, as almost “700,000 gallons of accident water” had seeped into the soil surrounding the Susquehanna River.[24] The Pane (People Against Nuclear Energy) Report of 1979 sought a departure from nuclear power. “To use coal we must demand the safest, cleanest coal possible, even though it means lower profits for the coal industry. With proper mine safety and miners rights, with adequate pollution controls and a strict program of land restoration, coal can continue to serve as an interim source of energy.”[25] Coal plants produced pollution that was easier to manage through desulfurization units that trapped the particles away from the atmosphere, versus nuclear plants that used uranium, resulting in “hundreds of dangerous radioactive elements with half-lives,” being stored at TMI.[26] As the protests became more widespread, the nation debated the Pane Report’s suggestions, suffering in the midst of a growing energy crisis.

Although the American Yawp textbook failed to include the Three Mile Island Incident of 1979, it leaves behind a complicated history that served as “a spark that ignited the funeral pyre for a once-promising energy source.” [27] It is important for history textbooks to mention the historical debate over nuclear energy that is rooted in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island Incident, holding corporations and government officials accountable for man-made disasters. The American public must be informed of nuclear energy’s long-term health and environmental effects on their fellow citizens to mark a return to more conventional nonrenewable energy resources in the future.

________________

[1] Seth Anziska et al., “The Unraveling,” Edwin Breeden, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

[2] “Three Mile Island,” Dickinson.edu, 2019, http://tmi.dickinson.edu/.

[3] “Three Mile Island,” Dickinson.edu, 2019, http://tmi.dickinson.edu/.

[4] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[5] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[6] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[7] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[8] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[9] Jefferey Blinn and Sarah Snyder, “College Responds to Three Mile Island Nuke Accident: Coping Student Exodus,” Three Mile Island Website (The Dickinsonian, April 12, 1979), http://tmi.dickinson.edu/index.php/category/item-type/newspapers/.

[10] “President Carter: Meltdown at Three Mile Island,” | American Experience | PBS (WGBH Educational Foundation), accessed May 4, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/three-president-carter/.

[11] “March 28, 1979: Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant Accident,” cbsnews.com (CBS Interactive Inc, March 28, 2019), https://www.cbsnews.com/video/march-28-1979-three-mile-island-nuclear-power-plant-accident/.

[12] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[13] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[14] “Three Mile Island,” Dickinson.edu, 2019, http://tmi.dickinson.edu/.

[15] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[16] Peggy Collins, “Small Crew Keeps WDCV Broadcasting,” Three Mile Island Website (The Dickinsonian, April 12, 1979), http://tmi.dickinson.edu/index.php/category/item-type/newspapers/.

[17] Victoria Daubert and Sue Moran, “Origins, Goals, and Tactics of the U.S. Anti-Nuclear Protest Movement,” March 1985, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2005/N2192.pdf.

[18] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[19] Audio recording with Karen Edler, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

[20] Thomas Fortuna, “U.S. Anti-Nuclear Activists Campaign against Restarting Three Mile Island Nuclear Generator, 1979-1985,” The Global Nonviolent Action Database (Swarthmore College, September 18, 2011), https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/us-anti-nuclear-activists-campaign-against-restarting-three-mile-island-nuclear-generator-19.

[21] Jenny Jordan, “Student Participates in Protest,” Three Mile Island Website (The Dickinsonian, April 12, 1979), http://tmi.dickinson.edu/index.php/category/item-type/newspapers/.

[22] “70,000 Stage Anti-Nuclear Rally in D.C,” The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), May 07, 1979, 2. https://envoy.dickinson.edu/loginqurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2F70-000-stage-anti-nuclear-rally-d-c%2Fdocview%2F1614163941%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

[23] “70,000 Stage Anti-Nuclear Rally in D.C,” 2. https://envoy.dickinson.edu/loginqurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers

[24] Patrice Flinchbaugh, “Nuclear Wastes from TMI2 Could Stay on Island for 25 Yeaes,” York Daily Record, August 26, 1980, http://tmi.dickinson.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2017/04/Article7.pdf.

[25] “PANE Newsletters,” (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections, 1979), http://archives.dickinson.edu/sites/all/files/files_tmi/PANE_1979.pdf.

[26] “PANE Newsletters.”

[27] Kiyosh Kurokawai and Meshkati Najmedin, “10 Years After Fukushima, Safety is Still Nuclear Power’s Greatest Challenge,” The Conversation : Environment + Energy, March 5, 2021, 1https://envoy.dickinson.edu/loginqurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2F10-years-after-fukushima-safety-is-still-nuclear%2Fdocview%2F2497315252%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D10506.

Selected Transcript

- Audio recording, Mahwah, NJ, April 20, 2021

Question: Where were you when you heard of the Three Mile Island incident? What was the reaction when the news first broke out?

Answer: When I first heard about the incident, I was in the now Global Community house, sometimes referred to as Todd House. It was early dawn on March, 28th 1979, and I had transferred into Dickinson College as a sophomore from the University of Delaware freshman honors program.

Q: Since social media, referring to Twitter, Instagram, and other various outlets, did not exist at the time, how fast did information spread around campus?

A: I think it took at least a day for it to spread around campus. When you were in class, professors would briefly mention it, but we didn’t have a lot of information about exactly what happened or how it would affect us.

Q: Did you have any previous conception of nuclear energy and its uses? Or were you mostly indifferent?

A: While I certainly knew nuclear energy existed, I didn’t have any negative feelings about it. To me, it was just a source of energy for the country. It was only after the three mile island accident occurred that I learned the dangers of nuclear energy and strict safety protocols that need to be in place. However, even with the safety protocols, I realized it could still endanger a large portion of our country.

Q: Were most students even aware of the existence of 3 Mile Island at the time? Did you have any prior knowledge?

A: I knew that there was some kind of a plant. I did not know it harnessed nuclear energy at the time. It was clear since we used to see it when my parents drove me to or from Dickinson because of the huge stacks and the smoke coming out from them. In fact, visiting Harrisburg with a friend, I drove right by the plant not long before this happened. Most people didn’t realize that it was a big nuclear plant unless you were studying in a physics field at the time. This accident was really what made us the most conscious that its existence wasn’t far from campus.

Q: What were the main modes of communication students used to gain information about the crisis at its initial breaking?

A: The main mode of communication about the three-mile island crisis was initially through television. It was common to see students in their respective dorms gathered around a single silver screen. It brought fast information on the rising crisis, especially through the local ABC Action News 27. It was due to the concerns of a reactor two meltdown, which would have put thousands at risk within the Carlisle area.

Q: When did you mention the incident to family members back home? Was it that Wednesday, or at a later date?

A: I did not initially tell my mother about the incident or the college asking people to voluntarily leave. I had a conversation with her days later when she became aware of it. She demanded that I come home because she was afraid I would not be safe. I called once a week on Sunday, so she became more fully aware of the situation on April 1st.

Q: What was the president’s initial response to the crisis? What did Dickinson do about the international students on campus?

A: I recollect that Dickinson asked us to voluntarily leave campus if possible on the first weekend after three-mile island. They asked people to leave by that Friday because they were going to be an evacuation center. No one was quite sure when these things were going to happen or how international students would be affected. Many international students did not have someplace to go easily, so they were permitted to stay if they lived too far from campus. The school didn’t shut down until the end of that weekend, but college President Samuel Banks decided to close the college for a full week. This was to keep the students safe, as many parents were worried and upset, leading to much nuclear hysteria.

Q: What role did Dickinson serve to those evacuated from the suburbs of Harrisburg and Cumberland County?

A: I understood that Dickinson was going to be used for residents of a nursing home that were evacuated and for a staging area for what we would call first responders today, fire companies, and others that were there to assist. It was a time of real uncertainty, and no one really understood what would happen exactly. Evacuation zones kept expanding as more information was learned about what was actually going on at the plant. I did not learn later that Dickinson used some of the professors and international students who could not leave campus at the time to interview and create archives of information about people’s experiences surrounding the incident.

Q: What part of the 3-mile incident was the average Dickinson student deeply concerned about? Did students think about its potential long-term effects?

A: People were really concerned about health problems as a result of the incident. Once we were past the point where people were concerned about a potential explosion, students knew radioactive gas had been admitted but didn’t understand how far it would go or whether it could reach dangerous levels at the campus. Many were worried about having long health side effects as a result. As a result, there were definitely more people on campus who became more interested in the anti-nuclear movement, as the accident at three-mile island really kicked conversations about the safety of nuclear energy into gear. Many people were worried, predicting there could be another nuclear accident in the future that could affect even more people in the country. What resulted in the aftermath of Three Mile Island was a big anti-nuclear energy protest in Harrisburg on April 8th, 1979, which called for the immediate closure of the plant.

Q: Where did you go when you were first evacuated? And how long did Dickinson keep students off-campus?

A: Initially, I left campus thinking it was just for the weekend. I went to my boyfriend’s dorm at the University of Maryland to stay for the weekend. But then, come Sunday, they announced that the school would be shut down for a week. At that point, my mother was furious that I decided to stay with my boyfriend for the weekend and ordered me to drive home back to northern New Jersey. I remember my mother driving along the Pennsylvania Turnpike when we returned to Dickinson College the following week, and you could still see quite an ominous cloud over the three-mile island. It left me with a sense of uneasiness initially, as I gauged my trust with local authorities who felt they contained the situation.

Q: As I am in the midst of an off-campus learning experience during the COVID-19 crisis, I am wondering did Dickinson students have any communication with professors during the week-long shutdown? Did you get a chance to get ahead on schoolwork?

A: We did not have any communication with our professors while the school was closed, and I recollect that the school made up the classes that we missed throughout the rest of the semester. It is not like today, where you could email and submit assignments through a computer or school portal.

Q: Since Dickinson has been the cornerstone of sustainable education, even in the 1970s, what was the reaction of Dickinson students to the incident when they returned to campus? Was there a shift in tone over nuclear energy?

A: Certainly, everyone was talking about nuclear energy and whether it was safe. The three-mile island incident kind of became a piece of the culture of our time at Dickinson, and many people began to at least look into any nuclear movement and learn more about what nuclear energy was. Many would speak out at the capitol in Harrisburg, questioning why the plant was close to residential neighborhoods.

Q: Reflecting on your time at Dickinson, do you feel the fallout from the Three Mile Incident was one of your most influential experiences? If so, why?

A: The aftermath from the Three Mile Island Incident definitely defined my time in Dickinson. It was certainly the most exciting thing that happened, exciting in a terrifying way. I think it also helped students bond some over a collective sense of fear for the future, similar to what current Dickinson Students are experiencing with the COVID-19 crisis. It opened a debate for how nuclear energy was being used at the time and how it might affect us going forward in our lives.