Video: Vietnam Veterans: America’s Other Vietnam Failure

Vietnam Veterans: America’s Other Vietnam Failure

By Sam Kistler

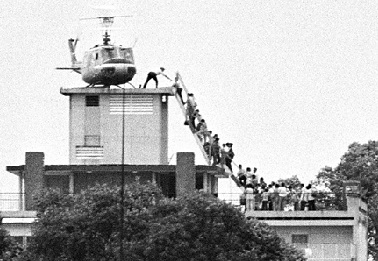

“The communist conquest completed America’s Vietnam debacle,” wrote H.W. Brands in his, American Dreams, referencing the Fall of Saigon and the ultimate end of American involvement in the Vietnam War. [1] The conflict, during which direct American military action lasted from 1965-1973, was highly controversial and contentious, and claimed the lives of nearly 60,000 American servicemen. [2] Set against the backdrop of America’s Cold War policy of globally containing communism, the unsuccessful and domestically unpopular conflict saw the United States militarily intervene in support of South Vietnam in their war against neighboring communist North Vietnam. After eight years of harsh fighting, and little, if any, true military success, US forces withdrew from Vietnam completely in 1973, and in April of 1975, the North Vietnamese captured the South’s capital city of Saigon, effectively concluding the war. However, while the fighting itself may have ended in the South Vietnamese capital on 30 April 1975, “America’s Vietnam debacle,” was far from complete.

While America’s geopolitical aspect of the Vietnam War ended with the cessation of hostilities in 1975, a domestic development of the war would continue for decades, one that many, including H.W. Brands, neglect to include in their analysis of the conflict: the plight of Vietnam Veterans. Upon returning from the failed war, often brining with them physical disabilities and mental struggles, American servicemen faced persistent hardships, with many finding both inadequate assistance in dealing with those hardships, and a seemingly ungrateful nation. Robert Van Loon had a front row seat to the predicaments of these Veterans. In 1971, after serving in the Army Reserves during the early years of the war, Van Loon began a career at the Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.), first working as a Benefits Claims Examiner in Buffalo, NY, and then as a Benefits Counselor and Officer-in-Charge in Rochester, NY until retiring in 2001. [3] As a Benefits Counselor, Van Loon dealt personally with Veterans, and he recalls being “inundated” with those who served in Vietnam. [4] “I interviewed and filed claims for many thousands of Vietnam Veterans,” he remembered. [5] As witnessed by Van Loon, throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, the men who had served in what was at the time America’s longest conflict would face struggles of an intensity greater than those faced by any Veterans who had come before. While the war was over for the rest of America, their fight was just beginning.

Unlike in previous conflicts, improved medical capabilities of the American military in Vietnam allowed for the survival of hundreds of thousands of wounded servicemen. However, this increased survival rate of the wounded also meant a much higher percentage of soldiers with physical disabilities after the war. In all, nearly 800,000 disabled came out of Vietnam, with almost 400,000 having been moderately to severely impaired. [6] These disabilities often prevented Veterans from living normal lives, and a great deal found their ability to participate in society quite limited. Most turned to government agencies such as the V.A. for help, receiving benefits and medical care. Many received the much needed assistance from the V.A., as Van Loon remembers, “a lot of people (Veterans) did like the V.A., and they liked getting medical benefits.” [7] However, the US Federal Government and the V.A. did come up short on some important fronts.

Most returning disabled Veterans came to the Department of Veterans Affairs to receive badly needed medical care, often administered at V.A. Hospitals. With hundreds of thousands of wounded and disabled servicemen, the V.A. would have needed to provide highly efficient and effective care to meet the needs of these men. This was, however, sadly not the case. V.A. hospitals were often overcrowded, and often lacked the ability to provide adequate care to their patients. “They should have spent more money on the medical part of the V.A.,” recalls Van Loon, in one of his critiques of his employer. [8] “There always seemed to be a shortage of doctors, and perhaps a shortage of nurses too.” [9] These shortfalls of the medical services of the V.A. are vividly illustrated in wounded Lieutenant Bobby Muller’s account of a V.A. Hospital in the Bronx, NY. “It was overcrowded. It was smelly. It was filthy. It was disgusting,” he recalled, while also going on to recount how the understaffed nurses were often too busy to assist him, and that the hospital even ran out of wheelchairs. [10]

Apart from the physical injuries that plagued many Vietnam Veterans, mental afflictions also followed the returning soldiers back home. Of the many former servicemen he dealt with, Van Loon recalls, “A lot of them had Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” [11] Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), an ailment seen in Veterans of most wars, is a mental illness resulting from memories of traumatic events such as combat, and was especially prevalent among Veterans of Vietnam, afflicting up to 15% of all the men who served in the war. [12] What’s more, as Van Loon remembers, it took years until these mental illnesses were identified, as PTSD itself only became a diagnosed mental disorder in 1980, leaving many Veterans to struggle with these afflictions on their own. [13] As a result, a good number of these Veterans were also increasingly unstable, highlighted by an encounter in which Van Loon was threatened by a Vietnam Veteran over a loan payment. “He saw it, he blamed me for it, and said he was going to shoot me with a shotgun,” he recalled, and while the man never went through with his threat, the encounter is a stark reminder of the mental difficulties faced by Veterans of Vietnam. [14]

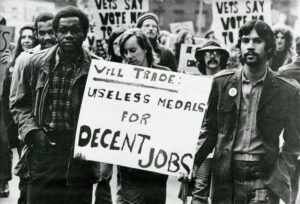

In addition to their medical difficulties, many Vietnam Veterans also heavily struggled financially. Developments in the mid-late 1970s caused energy prices and inflation to rise drastically in America, leading to increasing unemployment and ultimately a recession. [15] While their mental and physical injuries would have already caused them difficulty in finding work, returning home to a broken economy made it especially hard for many Vietnam Vets to secure employment. Furthermore, many of those who fought in Vietnam were prevented from finishing their educations, wether it be college or high school. Because of this, a large portion of Veterans found themselves working in low paying, low-skill level, unfulfilling occupations. [16] So, even for those who would find employment, the opportunities were quite slim and grim.

In light of their economic hardships, many Vietnam Vets would again turn to organizations like the V.A., this time for badly needed financial assistance. While the benefits provided by the federal government did help a good number of Veterans, there also those who felt that, once again, the systems in place to aid them had let them down. Many Vietnam servicemen found that the G.I. benefits that had greatly assisted World War II Vets in establishing post-war lives just three decades earlier were quite lacking, and even “nonexistent,” in the words of Veteran Peter Langenus. [17] In addition to the perceived weakness of the benefits, a number of tricky tacky V.A. regulations prevented some Vietnam Veterans from even receiving necessary aid at all. Van Loon highlights one of these regulations, “The V.A. had a regulation where they (Veterans) had to have gotten a medical determination within one year of leaving service, showing a disability.” [18] Many Veterans were unaware of the bylaw he refers to, and were consequently unable to receive their badly needed disability benefits, “Many of these guys just left service. There was no particular medical examination that they got and they complained, and you know, rightly so.”[19] An instance of this predicament can further be seen in the testimony of Peter Langenus, as he recounts contracting a severe disease specifically connected to Vietnam, after having returned to the U.S.. [20] Langenus recalls that he was unable to receive V.A. benefits or health insurance simply because he was unable to connect the affliction to his war-time service without an in-service medical examination. [21] With many already disabled, impoverished, and out of job, Vietnam Vets now also found themselves unable to receive their promised assistance.

In addition to their medical and financial plights, perhaps worst of all was they way many Vietnam Veterans felt they were treated by American society after the war. Throughout its course, Vietnam was an increasingly unpopular conflict in the United States, with anti-war protests erupting in cities and on college campuses across the country. [22] Because of this, a lot of Vietnam Veterans returned home to a much different kind of reception than they expected. While in most American wars of the past, Veterans were treated to great jubilee and celebration, Veterans of Vietnam were given much the opposite. [23] Many felt unappreciated for their service in the unsuccessful war, with some receiving outright hostility. While being transferred to the hospital upon returning to the United States, wounded Veteran Steven Wowwk recalls passing civilians and throwing up to them the two-fingered peace sign. [24] Wowwk claims that “instead of getting return peace fingers, I got the middle finger.” [25] Because of this kind of perceived resentment, many Vets felt ostracized from society, with the Oklahoma Historical Society even describing their treatment as that of “traitors.” [26] This perception of mistreatment towards Vietnam Veterans was, however, not shared by all. Van Loon himself believes that many of these stories of Veteran debasement, such as the one told by Wowwk, were often “apocryphal”, and that the people of America treated them more or less quite well. [27] While American society’s conduct towards Vietnam Veterans after the war is indeed up for debate, it is clear that at least some Veterans felt unappreciated and disrespected by their fellow countrymen after coming home.

While the War in Vietnam may have ended with the Fall of Saigon in 1975, “America’s Vietnam debacle” as H.W. Brands puts it, was far from over. The returning Veterans of the war who had risked their lives for their country, often faced disability and poverty, as well as a sense of contempt and stigmatization from the American people. And while employees of America’s Veteran-assistance institutions, like Robert Van Loon, did their best to aid these former servicemen, there were many Veterans who felt let down by their government when they needed them most. When asked if many of the thousands of Vietnam Vets he dealt with were happy with their lives, Van Loon replied simply, “No.” [28] Thankfully, it was not doom and gloom for all Vietnam Veterans. There were a good number who did manage to complete their education after the war, and some eventually established steady lives during the period of relative economic prosperity in the country during the late 1980s and 1990s. One such Veteran, John McCain, even became the Republican Nominee for President of the United States in 2008. However, despite the eventual success of some of these servicemen, many of the veterans of this unwanted and seemingly unwinnable conflict faced persistent struggles, whether it was destitution, or mental illness, or physical disability, and the end of their plight will be the true end of “America’s Vietnam debacle.”

Citations

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 175.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 175.

[3] Email Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 8, 2023

[4] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[5] Email Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 8, 2023

[7] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[8] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[9] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[11] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[13] U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PTSD and Vietnam Veterans: A Lasting Issue 40 Years Later (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Public Health, 2016); Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[14] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[15] H.W. Brands, 192-196, 203.

[18] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[19] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[20] Langenus Quote to The History Channel

[21] Langenus Quote to The History Channel

[22] H.W. Brands, 153-154.

[23] Dante Ciampaglia

[25] Wowwk Quote to The History Channel

[27] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

[28] Zoom Interview With Robert Van Loon, December 5, 2023

Interview Subject: Robert Van Loon, age 84, retired Officer-in-Charge, Department of Veterans Affairs, Rochester District. Former member of U.S. Army Reserves, 1962-1968.

Interview Transcript, December 5, 2023

Speaker 3 Hi, Sam.

Speaker 2 Hi. So I guess I’ll start off with. You were at one point in the Army yourself, right?

Speaker 3 I was in the Army Reserves for six years.

Speaker 2 And from what years were you in the Reserves?

Speaker 3 Um. From 1962 to 1968. And nicer. Yeah, I served six, six months regular active duty for training down at Fort Dix, New Jersey. And then I went back to Rochester and then I just went to meetings every Sunday. And then every year we would go to a 2 week summer camp for six years. So that’s what I did. Yeah.

Speaker 2 And then after your service, you worked at the VA, right? The Veterans Affairs?

Speaker 3 No, I worked. I work with the DHS, the Defense Contract Administration services for work there, maybe about a year. I left and then I went into teaching there. So I taught for about a year at West High School, and then I taught for a year, well, it was later on at Monroe High School, which was my old high school. I had my own homeroom. Then I went to the V.A..

Speaker 2 So Which office did you work at? Was it the Rochester office for the V.A.?

Speaker 3 No, I worked at the Chicago Chicago Regional Office of the VA in Chicago, Illinois. And I was there for almost two years.

Speaker 2 Okay. And what was your job at the VA.

Speaker 3 Um, I worked as a veterans benefit claims examiner. So I, you know, did a lot of paperwork for veterans educational benefits, disability benefits, either non service connected disabilities or service connected disabilities. And so that’s what I did at the Chicago VA. And I did that at Buffalo, too. And I finally ended up in Rochester, New York.

Speaker 2 So while you were there, did you come across a lot of veterans of Vietnam?

Speaker 3 Oh, yes. Yeah, quite a few. We were inundated, and I had a lot of claims that I looked over from Vietnam veterans. I had one guy, strangely enough, who got attacked by a tiger. Tiger jumped into his foxhole and dragged him out by the neck and his buddy shot the tiger and it turned up in The Army Times, they’re holding tiger. You know, they hung it up and so forth. The guy had gone out. He got a disability. So, yeah, but wasn’t hurt too badly.

Speaker 2 So when you interacted with these veterans of Vietnam, did they seem happy with the VA and did they seem that they felt they were being treated properly by the federal government?

Speaker 3 I’d say pretty much so. Pretty much so. I had. Mostly when I left Buffalo, I got a job as a veteran’s benefits counselor so that I dealt with veterans personally, either on the phone or in person filing claims for them to send them to our Buffalo Regional office, which that’s where the claim where I worked as a claims examiner also or had worked there before. But pretty much, you know, you do have complaints every now and then. But pretty much, you know, I think most people did like the VA, okay. And they liked getting benefits, you know, a lot of them were getting benefits. Or I should say medical benefits from the VA clinic, which was at the federal building and in Rochester for a long time before they moved out to a suburban location. And. And I moved out there with them. So yeah, I’d say most of them were pretty happy. You get occasional ones that complain about things. And you know, World War Two veterans sometimes complain. Most of the time it was complaints about hearing loss. And the VA had a, you know, had a regulation where they had to have gotten a medical determination, at least within one year of leaving service, showing a disability. And many of these guys, you know, they just left service. I mean, there was no particular medical examination that they got out or so forth and they complained and, you know, rightly so. But that was probably one of the major complaints that we used to get.

Speaker 2 Were there any specific interactions at the V.A. that came to mind? Or any people that you remember?

Speaker 3 Yeah, I’d say one time I was actually threatened. I heard this. I heard this from the nurses that from one of the veterans whom I had dealt with. He was getting a non service connected disability benefit which is based on income. That’s an income based benefit. And for some reason, he did not. He did not list that he owned property and that he was collecting rent from his property. And when he told me that, I had to put it down and I sent it in to Buffalo, to our regional office. And then they sent him a notice of a tremendous amount of overpayment. And he didn’t like that at all. And he blamed me for it. And he saw it and said he was going to shoot me with a shotgun. So. I actually had gone to the police there. And but they never they never did anything. They talked to me about it and, you know, so what. Oh. And nothing ever happened behind that. So.

Speaker 2 Do you think that there was anything that the V.A. or the federal government could have done differently to help veterans after the war?

Speaker 3 They could have spent more money. I think on the medical part of the V.A., I think they could have. You know, there always seemed like a shortage of doctors and. Perhaps too a shortage of nurses. There are always nurses around, but doctors seem to come and go. And some stayed and many were very good. Some of the ones who left, they probably should have left because they weren’t very good. But they could have spent more money on getting more doctors. I think for the VA clinics. And the hospitals, for that matter.

Speaker 2 Now, outside of the VA, did you know personally any people who fought in Vietnam?

Speaker 3 Who fought in Vietnam? Yes. Yes, I did. A friend of my brother’s had gotten drafted. And he was sent over to Vietnam and he was there. He was there for one day. And the enemy had mortared him and he ended up falling on his arm on a tent steak or something. So that was the end of the war for him. And he was all right after that. But he got a decent disability compensation. That’s not a large amount, but it’s, you know, minimal. That’s the only person that I really knew outside the VA who was in Vietnam.

Speaker 2 So did you. I know you say that all of these veterans were more or less happy with the VA. Did they seem happy with their lives?

Speaker 3 No. A lot of them had post-traumatic stress disorder. But this wasn’t really, this didn’t become a big thing until maybe years later when they really knew. And it was affecting a lot of these veterans. And there was, you know, and it’s just something that I think happens because of the fact that they’re engaged in such really awful, awful warfare. Yeah. I mean, they saw a lot of terrible things. And, you know, that’s just something that happens, I think, to anybody who’s probably caught in a traumatic or frightening event. And you can’t get more frightening than combat.

Speaker 2 And apart from the VA and overall, how would you say that the American people treated people coming back from Vietnam?

Speaker 3 I think that they treated them well. I think a lot of the stories that you read are apocryphal stories like people spitting on veterans and so forth in the back or we didn’t nobody, nobody really felt that way. I mean, it’s possible there were a few people who did something like that. I can’t imagine it. But it’s something that just spread. And a lot of some veterans like to spread those things. Mm hmm. That makes them feel more important or whatever. So, yeah. But I don’t think that that happened very much. If at all, even.

Email Interview, December 8, 2023

Q. Do you remember the exact years you worked at the V.A.?

A. I started as a VA Claims Examiner at the Buffalo, NY Regional Office of the VA in September 1971. Worked in Rochester, NY as a VA Benefits Counselor, and then as VA Benefits Officer-in-Charge of the Rochester region until I retired in July, 2001.

Q. Do remember if most of the Vietnam Veterans you dealt with were doing well financially?

A. It depended on the benefit the veteran sought. I issues VA loan guarantee certificates for home purchases, applications for college, and trade schools. If the veteran had a low disability percentage, they were perhaps doing well. However, most of the veterans who applied for benefits were not doing well financially. As to numbers, I couldn’t brake it down. I interviewed many thousands of Vietnam veterans.