Technology on Wall Street Since 1987: for Better or Worse

By: Charlie Luparello

Courtesy of Investment U

In 1987, Steve Luparello was working as a junior lawyer for the SEC, in its Division of Market Regulation. The group was responsible for overseeing and regulating a number of different participants in the markets, including brokers and exchanges. The months leading up to October 19, 1987 were comparable to the other stock market crashes in United States history. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was at a high and the market continued to rise steadily. Traders were experiencing great success, prompting even people with little market experience to test their chances.

One of the main factors behind the markets success was program trading. Program trading was a method used by traders in which an automated system bought and sold stocks once the value reached a certain level, and was usually used by larger companies.[1] Although at the time, many traders considered program trading a flawless system, eventually issues began to become evident. Originally, program trading worked as intended. The problem with program trading was the program assumed the person controlling it was the only one buying and selling, when in fact many traders were using the same method. Although there were warning signs of the possible shift of the stock market, traders and investors carried on with their routine. Eventually, on Friday October 16, 1987 the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted. The DJIA dropped 108 points on that day, making it the first hundred-point loss in a twenty-four-hour period. People involved with the stock market were frustrated by the drop, but knew 108 points was manageable. The next trading day, Monday the 19th, the market went from bad to worse. On the morning of Monday October 19, 1987, the DJIA had an initial drop of 200 points.[2] When asked about his reaction to the initial drop Luparello responded, “In some ways there was fear, because there really was no telling how far the market would fall and what that might do to the overall economy.”[3] The fear was justified, as by the end of the day the DIJA dropped a total of 508 points, the largest loss on a single day in stock market history. October 19th, which later became known as Black Monday, was worse than any single day during the Great Depression and had many fearing a profound effect on the economy.[4] In addition, the United States was not the only stock market that experienced difficulties. After the October 16th drop other major foreign stock markets crashed including Tokyo, London and Frankfurt.[5]

During 1987 Stock Market crash regulators suffered from a lack of technology. When asked about how an absence of technology affected Luparello’s situation, he responded, “…the lack of sophisticated technology also added to the level of surprise that we experienced during the event. If our monitoring tools were as ‘modern’ as the trading systems, there was a chance we could have put certain protections in place to minimize the size of the crash.”[6] The SEC did not have the advanced technology to easily deal with the events that were unfolding, because advancements that occurred on Wall Street were more complex and sophisticated.

A common theme in the stock market is that new technology will be developed and regulators will create new rules and advancements to counter the traders. The issue regarding the Crash of 1987 was the newest technology on Wall Street ultimately contributed to the crash. Many traders considered program trading the future of Wall Street. For a period of time, program trading was making people a large sum of money and everybody thought they had solved the puzzle of stock trading. The regulator’s response to the issue program trading brought was to implement circuit breakers.[7] Circuit breakers prevent panic selling and ensure the DJIA will never move too far too fast. With circuit breakers in place there is little fear of another crash based of program trading.

Since the crash of 1987, the stock market has constantly evolved and developed new technology. Although the stock market crash was only thirty years ago, the stock market today is completely different than in the past. A major change in the past thirty years is the diminished roles of New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. During 1987 the NYSE and NASDAQ were titans of the stock trading industry. Today, the NYSE and NASDAQ are still the two biggest exchanges in the country, but control significantly less activity due to more competition.[8] Technology has given traders an easier and more efficient way to trade. In the late 1980’s, stock trading involved a significant amount of human interaction. Now everything is online and the entire process is easier. The internet is a major reason why trading has become a faster process. Present day traders can do research, buy, and sell stock from anywhere. Luparello discussed the downfall of the role of people involved with the stock market by stating,“Pre-1987, human beings still played a big role, always deciding what to buy, but also pretty much using human instinct on how to buy. Now, human touch is still a big part of what to buy, but computer algorithms control the how, and if humans tried to compete, they would lose.”[9]

Courtesy of CNBC

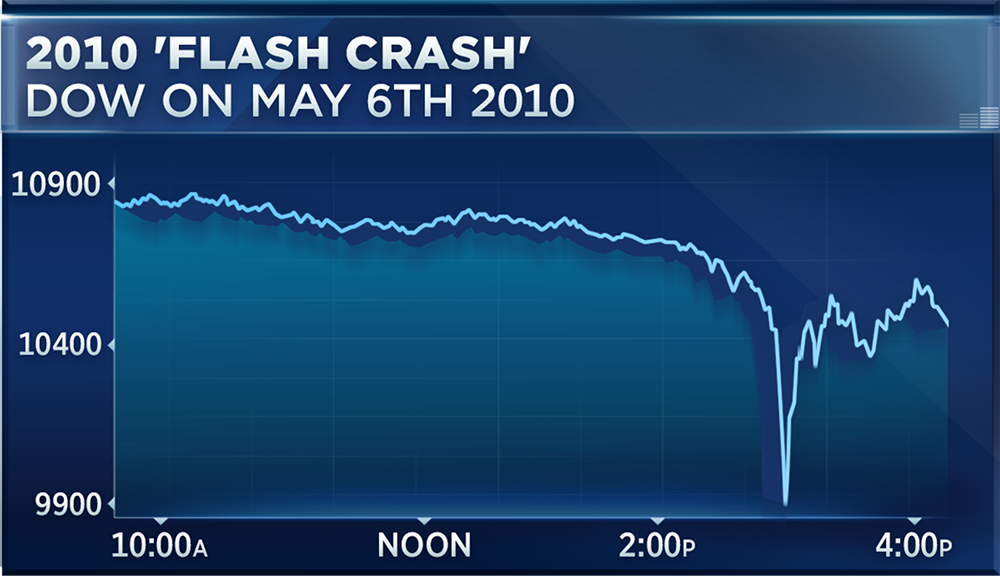

When traders develop new technology, it is usually in an attempt to make trading stocks easier and quicker, and sometimes that creates problems in the stock market. Regulators will then need to create a solution to the problem the traders have created, and this often calls for the creation of new rules or new technology. In 2010 the S&P 500, the DJIA, and the Nasdaq suddenly dropped and quickly recovered with little know reason. The quick collapse of the exchanges became known as the Flash Crash.[10] As a response to the Flash Crash regulators forced markets to create market access controls. Market access controls limit the total amount of orders sent out on the market at a single time, which makes another flash crash much less likely. In an ideal world, regulators could develop strategies that would stop market disasters before they happened, but that type of forward thinking is very challenging.

Throughout American Dreams, the author, H.W. Brands, references the theme that America will continuously advance and technology will help drive it. New technology creates a quick change in people’s lives. A quick change may be beneficial, but can also be harmful. New technology will be developed and this creation will make everyday life easier, but because technology can create risk, legislators may have to create certain rules regarding these advancements. Wall Street is similar to the real world because whenever traders develop a new system or method, usually regulators will have to construct rules in response. Ideally, regulators would be able to control the stock market and prevent any difficult situations with the technology that they have acquired. For example, regulators create new responses based off what the market has already experienced. Luparello described the situation as, “But the reality is that regulator’s tools always lag behind the tools the market uses.”[11]

Technology on Wall Street and in the real world have certain parallels. A cell phone ten years ago would be a large piece of plastic with the sole purpose of calling. In the present day, a smartphone is not only a phone, but also a computer, a watch, and a camera, among other things. But progress brings risk. New technology may lead to stress, distraction, or a higher level of deception. Although technology backfires, often new advancements are beneficial.

Just like on Wall Street, new legislation is necessary in order to control new technology. Certain laws have been placed on new technology, such as the internet, regarding what can and cannot be done. must be progressive. For both Wall Street and the real world, new technology is essential because the world must progress. It is important however because new technology can be either harmful or beneficial, for regulators to monitor and control it.

[1] Dean Furbush. “Program Trading.” Library of Economics and Liberty. (2002)

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 265

[3] Email interview with Steve Luparello, November 5, 2017

[4] Ronald H. Filler, “When All Else Fails.” Financial History, no. 188 (2016): 32

[5] Ulrike Schaede, “Black Monday in New York, Blue Tuesday in Tokyo: The October 1987 Crash in Japan.” California Management Review 33, no. 2: 42

[6] Email interview with Steve Luparello, December 3, 2017

[7] Schaede, 39

[8] “U.S. Equities Market Volume Summary.” Cboe Global Markets. Accessed December 07, 2017. http://markets.cboe.com/us/equities/market_share/.

[9] Email interview with Steve Luparello, December 3, 2017

[10] Edgar Ortega Barrales, “Lessons From the Flash Crash for the Regulation of High-Frequency Traders.” Fordham Journal Of Corporate & Financial Law 17, no. 4: 1196

[11] Email interview with Steve Luparello, December 3, 2017

SELECTIONS FROM INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS

-Email, November 5, 2017

-Email, December 3, 2017

Selected Transcript

Q. “What was your initial reaction upon learning of the drop of the Dow Jones Industrial average, and what was the overall mood of the work place?Did you have any fears after realizing the situation, if so, what were they?”

A. “Some different emotions, as you would expect. In some ways there was fear, because there really was no telling how far the market would fall and what that might do to the overall economy. But in other ways, there was excitement. I know this doesn’t sound all that great, but my colleagues and friends were mostly young, relatively recently out of college or law school, and much more likely to have student loan debt than to have big stock portfolios, so there wasn’t really a direct personal concern. And I think we sensed that the event was going to change our jobs, and so that seemed kind of exciting.”

Q. “What effect did the lack of technology have on your specific situation?”

A. “In the immediate aftermath, it meant that we had to try to understand a market that had a large technology component using shockingly manual tools, like eyeballing pages and pages of old fashioned computer printouts and doing calculations by hand. But the lack of sophisticated technology also added to the level of surprise that we experienced during the event. If our monitoring tools were as “modern” as the trading systems, there was a chance we could have put certain protections in place to minimize the size of the crash. But just a chance.”

Q. “What major changes has the Stock Market seen since 1987?”

A. “It is a completely different place than it was 30 years ago. Back then, NYSE and Nasdaq completely dominated the market, handling 90+% of activity in the stocks listed on their markets. Today that number is closer to 20%, as they face competition unlike anything they have seen before. Then, people running around on the floor of the NYSE was a major way trading got done. Now the floor of the NYSE barely matters at all. The amount of trading that occurs on an average day is about 25 times larger than it was at the time. What would have been a record day in 1987, would now be done in a slow hour. But obviously, the biggest change is technology. Pre-1987, human beings still played a big role, always deciding what to buy, but also pretty much using human instinct on how to buy. Now, human touch is still a big part of what to buy, but computer algorithms control the how, and if humans tried to compete, they would lose.”

Q. “What important technological changes has the market adopted since 1987, and has the addition of newer technology helped prevent possible disasters?”

A. “It’s a bit of an endless race. The market develops new technologies and strategies, and the regulators respond with new technologies, and with new rules. That works pretty well in terms of making sure that we don’t have a market crisis that looks like a previous market crisis. For example, I think we figured out immediately after 1987 how to prevent program trading from sending a market into free fall, mostly through the creation of rules called circuit breakers, so we knew how to prevent a repeat. Likewise, after the Flash Crash, regulators required the markets to create what are called “market access controls, “which puts a limit on the number of orders that can be sent to the market at one time. Those rules, and the technologies to implement the rules, makes another Flash Crash highly unlikely. What’s harder is trying to figure out how to prevent a completely new disaster.”