by Dmitri Gvozdev

From 1961 to 1964, Marland J. Burckhardt served as a junior enlisted soldier in the U.S. Army, working in administration and logistics at Camp Darby in Italy.

Sophia Loren visits U.S. soldiers at Camp Darby near Leghorn (Livorno), Italy (Source: Getty Images)

H. W. Brands described this period of the Cold War in Europe as “comparatively stable.” According to him, “Berlin still caused tension, but for the most part NATO secured the western half of the continent on America’s side, while the Warsaw Pact, an alliance established by Moscow in response to NATO, held sway over the eastern half.”[1] However, this apparent stability was fragile and could have been disrupted by ongoing events. Burckhardt recalls his major warning, “This might be it. This might be the big one,” reflecting the shared fear that a single incident could trigger a full-scale war.[2] Based on a personal interview with Burckhardt and other primary and secondary sources, this essay focuses specifically on military personnel—on both sides, across different ranks—who experienced the rising tensions hidden beneath the “stability” that Brands describes. Each event had the potential to provoke a larger conflict between the two superpowers, keeping soldiers perpetually on edge.

In August 1961, construction of the Berlin Wall began. Brands characterizes this episode as “a settlement that might have allowed both sides in the Cold War to catch their breath if not for troubles elsewhere.”[3]

However, according to soldiers’ recollections, the experience was far from smooth. In Burckhardt account, constructing the Wall heightened tensions—especially among those in command, who were determined that existing military plans remain executable under such conditions.[4] Soviet troops felt similarly unsettled. Petr Levchenko, Chief of Air Defense for the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany from 1960 to 1967, recalled in a personal interview the so-called “tank silence” during the brief standoff at Checkpoint Charlie: “This tense stand-off lasted several days. Neither side fired a shot—there was not a single movement.”[5] Thus, there was no respite from these strains, and the Wall itself became the quintessential symbol of the Cold War, underlining the contrast that was noted: “West Berlin was busy, vibrant, and colorful; East Berlin was drab and gray.”[6]

During this period, the Soviet response to the deployment of U.S. nuclear missiles in Turkey was to place their own nuclear missiles in Cuba.

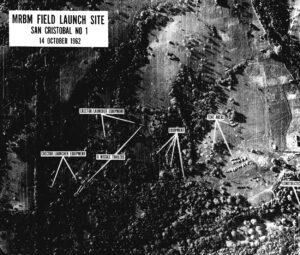

One of the first U-2 reconnaissance images of missile bases under construction shown to President Kennedy on the morning of 16 October 1962 (Source: Wikipedia)

In his October 22, 1962 speech, John F. Kennedy characterized the decision as “intended to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.”[7] However, views on the potential use of nuclear weapons among soldiers were mixed. According to David Stone’s article, soldiers on both sides of the conflict, on the one hand, believed that nuclear bombs could secure a swift victory, but, on the other hand, regarded their use as “horrifying” and “dishonorable for the military profession.”[8] The Cuban Missile Crisis created intense tensions between the two nuclear superpowers and provoked a similarly urgent reaction within the military. Burckhardt recalled it as “a big one” that could have led to war, noting that everyone was preparing for the worst:

All the officers and leaders were fully engaged in updating every contingency plan so they could carry out their duties if conflict broke out. I recall the major flying to France for a couple of days to synchronize our plans with those of other installations. During the crisis, our maintenance area was filled with tanks and heavy equipment one day and completely empty the next as everything was loaded onto trains bound north. Although I never saw the convoys depart, their sudden disappearance made their destination clear. [9]

Russian soldiers, too, experienced considerable tension and uncertainty during this period and were prepared to act. Levchenko recalled his service in Berlin as marked by near-constant suspense. Air regulations were exceptionally rigid, and the Soviet Air Force enforced airspace control with the utmost strictness under the Potsdam Agreement.[10] For example, he remembered a 1962 incident in which a Czechoslovak Il-18 transport aircraft was almost forced down for violating GDR airspace.[11] He noted that the protocol for border violations was uncompromising,

which ultimately led to the downing of an American B-66 combat reconnaissance aircraft that had illegally entered GDR airspace. Levchenko recalled that the situation was resolved peacefully because the Americans—adhering to the old Eastern proverb, “It’s better to see something once than to hear about it a thousand times”—acknowledged that it was indeed a combat aircraft.[12] This example underscores that both sides were prepared to act when necessary, yet the situation did not escalate.

In general, one cause of uncertainty during this period was the limited sources of information. Burckhardt recalls that coverage of events in Europe was constrained: one could only consult U.S. military newspapers, local newspapers, or radio broadcasts in local languages.[13] This uncertainty was especially acute after JFK’s assassination on November 22, 1963. No one was certain what would happen next, and the prevailing question was, “Would the Soviets benefit from this or not?”[14]

However, aside from the constant tension during his duty, Burckhardt recalls the freedom of movement throughout Italy when off duty: a military pass allowed overnight stays, and leave permitted several days away. With permission, it was also possible to travel freely across Western Europe, crossing into Switzerland and Germany with our ID cards.[15] According to Alair MacLean’s research—based on interviews with Cold War veterans—for peacetime cohorts, military service most often functioned as a neutral transitional role.[16] Thus, it could be seen as far less stressful and dangerous than participation in combat operations.

Although Brands considers 1960s Europe as stable, crises—from the Berlin Wall tensions and strict air-space enforcement in Germany to the Cuban Missile Crisis and JFK’s assassination—kept both superpowers on constant alert. Yet soldiers’ off-duty lives remained surprisingly routine. These findings suggest that, while Brands’s thesis is not entirely inaccurate—no open conflict erupted in Europe, compared with other regions—it requires clarification, since tensions were so high on both sides that any misstep could have escalated into a full-scale war.

References

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2010), pp. 91-92.

[2] Personal Interview with Marland J. Burckhardt, April 11, 2025, Carlisle, PA

[3] Brands, American Dreams, p. 104.

[4] Personal Interview with Marland J. Burckhardt,, April 25, 2025, Carlisle, PA

[5] “Lessons of the Cold War in the Peaceful Sky of the GDR: Memories of Service during the ‘Cold War’ Period (1960–1967) of General P. G. Levchenko,” Air Navigation Without Borders, December 23, 2020 // “Уроки холодной войны в мирном небе ГДР: Воспоминания о службе в период ‘холодной войны’ (1960–1967 гг.) начальника войск ПВО Группы советских войск в Германии генерала Левченко П.Г.,” Аэронавигация без границ, 23 декабря 2020, URL: https://ecovd.ru/uroki-holodnoj-vojny-v-mirnom-nebe-gdr/ (accessed May 7, 2025).

[6] Personal Interview with Marland J. Burckhardt, April 25, 2025, Carlisle, PA.

[7] Brands, American Dreams, p. 106.

[8] Personal Interview with Marland J. Burckhardt, April 25, 2025, Carlisle, PA.

[9] D. Stone. ‘The Military,’ in Richard H. Immerman, and Petra Goedde (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Cold War (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 28 Jan. 2013), pp. 352-353.

[10]-[12] Memories of Levchenko.

[12]-[15] Personal Interview with Marland J. Burckhardt, April 25, 2025, Carlisle, PA.

[16] A. MacLean. “The Cold War and Modern Memory: Veterans Reflect on Military Service.” Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 2008, 36(1), 103-130.

Appendix A. Selected Interview Transcripts

“Europe, where the Cold War began, had been divided and was comparatively stable [durning mid-1950s – early-1960s]. The anomalous condition of Berlin still caused tension, but for the most part NATO secured the western half of the continent to the American side, while the Warsaw Pact, an alliance stablished by Moscow as a riposte to NATO, held down the eastern half.” (Brands, American Dreams, pp. 91-92)

Interviews were conducted in person in Carlisle, PA, on April 11 and April 25, 2025.

Interview subject. Marland J. Burckhardt (born March 22, 1941; 84 years old). From 1961 to 1964, he served as a junior enlisted man in the U.S. Army, working in administration and logistics in Italy, Camp Darby.

Q: Could you tell me more about your first Army period in Europe during the Cold War?

A: My first tour in Europe was from summer 1961 to spring 1964 as an enlisted soldier in a logistical maintenance unit in Italy. We had our own Mediterranean port where German tanks came for overhaul—cleaned, parts replaced, returned nearly as good as new—and stored weapons and equipment for a potential conflict. I was stationed there when the Berlin Wall went up, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and when President Kennedy was assassinated. The Cold War required the U.S. to maintain hundreds of thousands of troops in Europe, and all eligible young men faced the draft unless they enlisted—by enlisting for three years, I chose Europe as my assignment. The ever‑present threat of war lingered at the back of our minds.

Q: Could you recall how major events affected it, if possible?

A: During that period, we had the wall go up in Berlin, the missile crisis, and Kennedy’s assassination. Those were the three big events.

During that time, each rise in tension brought concern about whether the Soviet Union would try to take advantage or push beyond where they were. When the wall went up, our tensions rose. The people in charge—of which I wasn’t one—were concerned, and there was a good deal of activity to ensure that military plans were current and that everybody knew what they would have to do if it went beyond just the wall.

Later on, I went on leave and flew into Berlin in a military aircraft, passing through Checkpoint Charlie, where Americans could enter the East German zone. I don’t remember the date, but it was obviously after the wall was up. What I remember most was the contrast: West Berlin was busy, vibrant, and colorful; East Berlin was drab and gray. We had to stay alert, wear our American uniforms, and later visited various places in the city.

As far as the wall was concerned, tensions went up and then eased for a while. Then came the missile crisis. Tensions ran very high because we were a logistical base with a lot of equipment in Italy, much of which went north into Northern Europe—Germany in particular—to be used if war broke out.

Throughout that entire period, the Cold War threat from the Soviet Union was constant. One of the reasons I was in the Army was because of the draft: able-bodied young men knew they would have to serve. In the missile crisis, tensions were extremely high. The people I worked for were deeply concerned. I remember a major saying, “This might be it. This might be the big one,” meaning it could start a war. They ran through all their plans to make sure they were current and that, if initiated, everyone knew what to do.

Our coverage of those events was limited. We didn’t have social media—only newspapers, radio, and a little TV. When Kennedy was assassinated, tensions rose again, and we worried about whether the Soviet Union would take advantage. In all three instances, tensions spiked and then subsided once things cooled off. The higher someone’s rank, the more concerned they were and the more they understood the conflict’s potential.

I understood the potential for conflict, but I don’t recall thinking there was much I could do. I was there and had to follow orders. A complicating factor was the strong Communist influence in Italy at the time. As young soldiers, we were warned to avoid any Communist gatherings. When not on duty, we had free movement throughout Italy: a pass allowed overnight stays; a leave allowed several days away. With permission, we could travel freely across Western Europe, crossing into Switzerland and Germany with our ID cards.

There was a huge American presence in Europe—communities of wives and children, hundreds of thousands of military personnel and their families. Tours were generally three years, and families moved with the service member. They lived in quarters—houses within local Italian, German, or French communities—and we had our own recreation areas. It was a subculture of Americans in Europe, especially in West Germany.

Q: Could you remember something special about the Cuban Missile Crisis?

A: Remember the missile crisis: the major I worked for warned this could be “the big one” that might start a war. All the officers and leaders were fully engaged in updating every contingency plan so they could carry out their duties if conflict broke out. I recall the major flying to France for a couple of days to synchronize our plans with those of other installations. During the crisis, our maintenance area was filled with tanks and heavy equipment one day and completely empty the next as everything was loaded onto trains bound north. Although I never saw the convoys depart, their sudden disappearance made their destination clear. Duty was generally good, but tensions occasionally ran high—everyone felt the strain. Otherwise, it was excellent duty for a twenty-one-year-old; I actually turned twenty-one while stationed in Italy.

Appendix B. Selected Episodes from Levchenko’s Memories (Translated)

Petr Gavrilovich Levchenko served as Chief of Air Defense Forces for the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany from 1960 to 1967, during the Cold War.

“Tank Silence” on the Berlin Border (October, 1961)

“…On the night of August 13 [1961], by decision of the GDR government, the borders with West Berlin—and indeed with West Germany as a whole—were closed. In a provocative move, U.S. forces deployed M-60 tanks along the boundary of West Berlin. In response to these provocations, the command of the Soviet Forces in Germany positioned its own tanks, fully combat-ready, at a distance of 30–50 m from the American tanks. This tense “standoff” lasted several days. Neither side fired a shot—there was not a single movement—and journalists later dubbed it the “tank silence.” Ultimately, the American tanks withdrew first; only then did our tanks pull back.

On August 13, 1962, construction of the Berlin Wall was completed along the entire border with West Berlin.”

Near-Tragedy of the Il-18 Border Violation (Autumn, 1962)

“…In the autumn of 1962, another curious—and almost tragically ending—incident occurred involving a Czechoslovak transport aircraft, an Il-18, on its routine scheduled flight from Copenhagen to Prague.

The weather in southern GDR was cold, with almost continuous cloud cover and powerful storm formations. Under these conditions, the pilots chose to skirt a cumulonimbus bank on the left and thereby violated the GDR’s state border—though we only learned of it afterward. At first, the aircraft was treated as a Western intruder. Scrambled interceptors engaged it, and I reported this to General Yakubovsky, who immediately ordered: “Destroy the intruding aircraft.”

Just then, our interceptor pilots positively identified the Il-18 by its Czechoslovak markings and relayed this to their own command post. Simultaneously, the commander of the interceptor squadron received from our combined command the order to shoot down the intruder. I at once informed General Yakubovsky that this was a Czechoslovak plane.

He drew a deep breath and said, “Thank goodness they didn’t shoot it down.”

In that way, the innocent lives aboard the Il-18—no fewer than a hundred people—were saved.”

B-66 Incident (March 10, 1964)

“…One sunny day, when almost the entire leadership of the Ministry of Defense was gathered on Hill “Kruzhka” at the Magdeburg training ground, General I. F. Modyaev reported that a Western combat aircraft had crossed the GDR state border and was flying toward the Magdeburg range. Our fighters were being vectored in to intercept the intruder and were awaiting orders. Modyaev then added that the pilots had identified the aircraft by its U.S. markings as an RB-66.

I gave the order to force the plane down—and, if it refused, to open warning fire. Modyaev reported that, even after warning shots, the intruder still would not land, and so he was ordered to destroy it. General Modyaev and a team of officers then flew by helicopter to the crash site. About an hour and a half later, he returned and told everyone on Hill “Kruzhka” that the downed aircraft was indeed a U.S. RB-66 tactical reconnaissance plane. To prove it, he brought back its flight log, on which “RB-66” was stamped in large English letters. The aircrew had been recovered and sent to the Stendal hospital.

Shortly thereafter, Army General I. I. Yakubovsky landed by helicopter. After hearing Modyaev’s report, he turned to me and asked, “Was everything done according to regulations?”

“Yes,” I replied to the Supreme Commander.”

Appendix С. Sources for Further Research

Gaddis, J. L. The Cold War: A New History. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Lafeber, W. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1966. New York: Wiley, 1967.

MacLean, A. “The Cold War and Modern Memory: Veterans Reflect on Military Service.” Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 2008, 36(1), 103-130.

Stone, D. ‘The Military’, in Richard H. Immerman, and Petra Goedde (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Cold War (2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 28 Jan. 2013)