Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919)

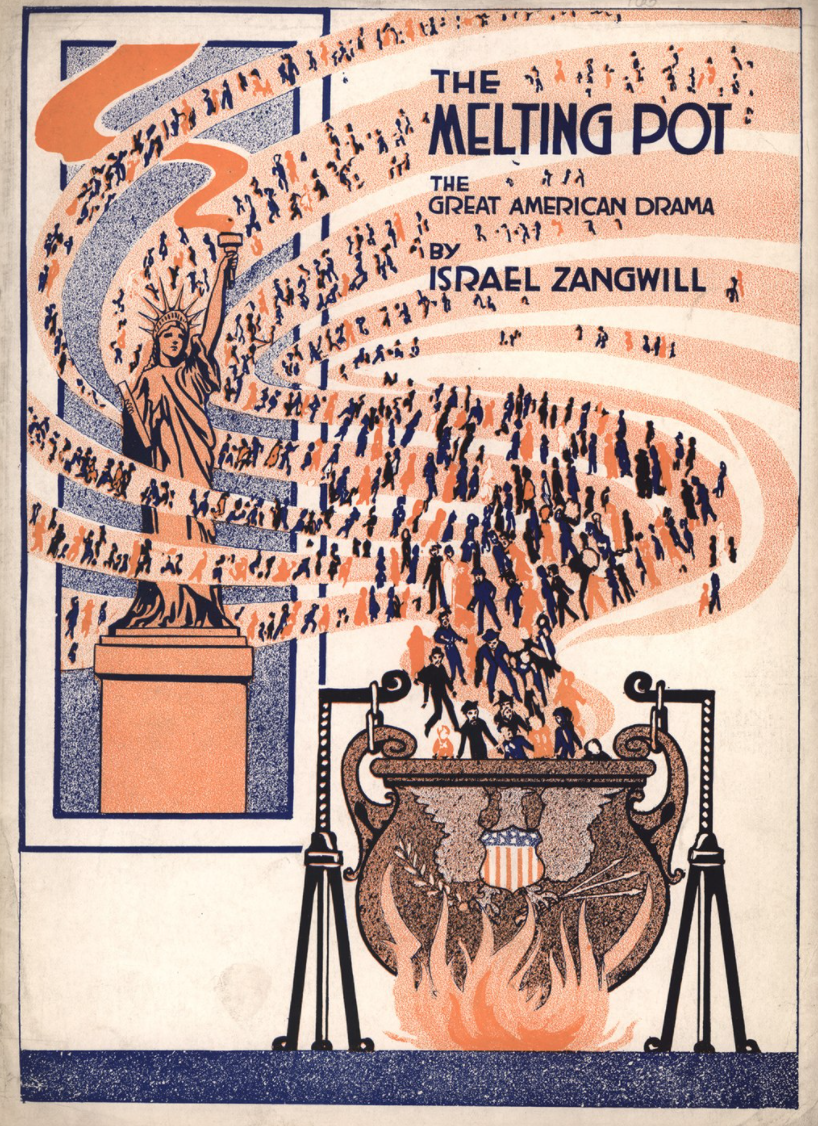

“Roosevelt’s nationalism expressed itself as a combative and unapologetic racial ideology that thrived on aggression and the vanquishing of savage and barbaric peoples. From the perspective of that ideology, it was vital that “Americans” cultivate their racial superiority and expel or subordinate the racial inferiors in their midst. Yet, Roosevelt also located within American nationalism a powerful civic tradition that celebrated the United States as a place that welcomed all people, irrespective of their nationality, race, and religious practice, as long as they were willing to devote themselves to the nation and obey its laws. Moreover, Roosevelt loved the idea of America as a melting pot-a “crucible”-in which a hybrid race of many strains would be forged. Mixing of this sort, Roosevelt believed, had created and would sustain American racial superiority. His affection for the melting pot expressed, too, the personal delight he took in crossing social boundaries and meeting diverse groups of people.” —Gary Gerstle

Timeline

- 1882 // Chinese Exclusion & Immigration acts

- 1883-86 // Tom Torlino attends Carlisle Indian School

- 1886 // Protests and violence at Haymarket Square in Chicago

- 1886 // Statue of Liberty dedicated

- 1887 // Dawes Allotment Act

- 1889-96 // Theodore Roosevelt publishes Winning of the West

- 1892 // Peoples’ Party organizes for presidential campaign

- 1892 // Ida B. Wells launched a national anti-lynching campaign

- 1893 // Panic begins with an even deeper downturn than 1873

- 1893 // Frederick Jackson Turner presents “frontier thesis”

- 1894 // Federal government intervenes in railroad strike

- 1896 // McKinley defeats Bryan in heated presidential contest

- 1898 // War with Spain

- 1898 // Hawaii annexation

- 1899-1902 // Philippine Insurrection

- 1899-1900 // Open Door Notes

- 1900 // US leads world in manufacturing output

- 1900 // McKinley defeats Bryan in presidential rematch

- 1901 // J.P. Morgan organizes US Steel, the first billion dollar company

- 1901 // Roosevelt becomes president after McKinley assassination

- 1903-1914 // Panama Canal

- 1904 // Roosevelt Corollary to Monroe Doctrine

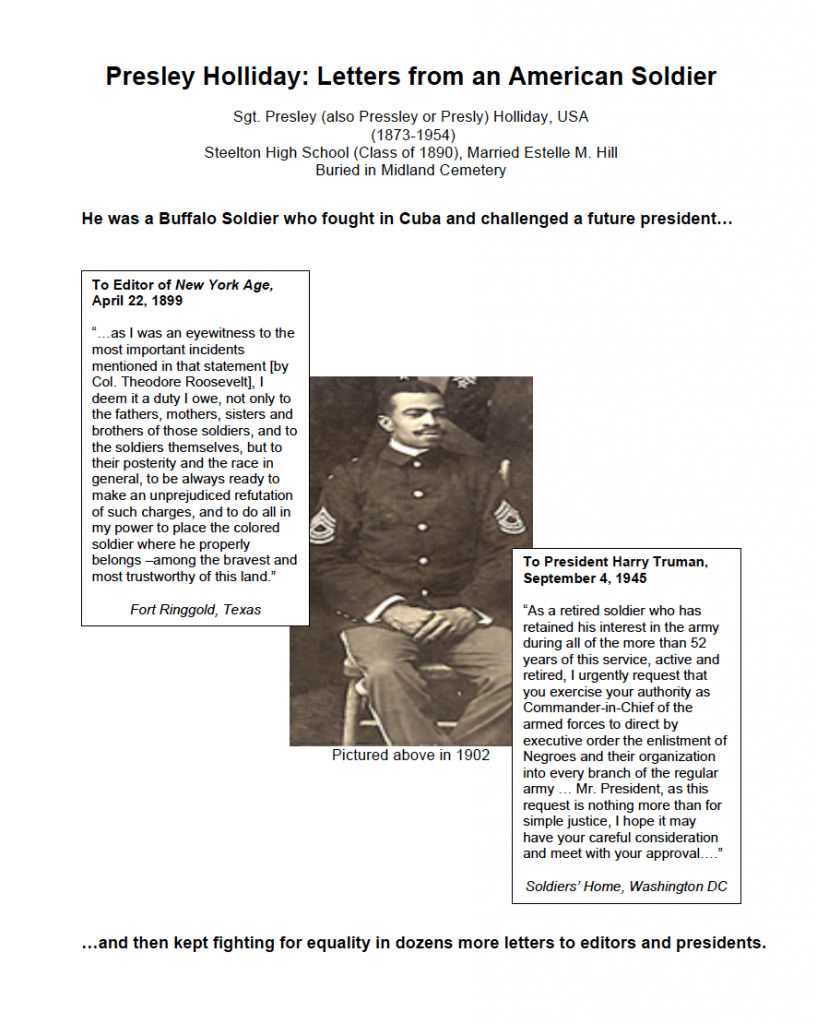

Who were the imperial soldiers?