What does the story of Prince Rivers teach us about the period of Reconstruction?

House Divided Project, The Prince of Emancipation (Google Arts)

Emancipation

Emancipation

- Runaway // Contraband // Freedman // Activist // Emancipator // Witness

- Wartime

- Color Bearer // Soldier / Provost Sergeant // Delegate

- Reconstruction

- Landholder // Politician // Leader // Judge // Outcast // Veteran

Image Gateway

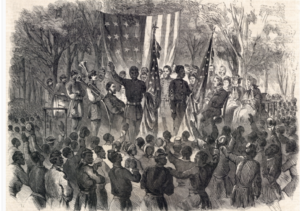

- For more background on this image, see Civil War & Reconstruction Online

Overview

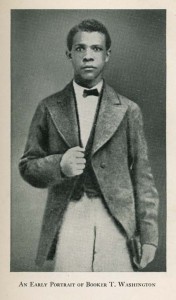

The term “Reconstruction” has more than one meaning in American history. Usually it refers to the period from 1863 to 1877, as the federal government worked to “reconstruct” or “restore” former Confederate states back in the national system of political representation. This was a controversial effort that often pitted the major political parties and the federal branches against each other, but ultimately all of the former rebel states returned to their place within the union by the early 1870s. But after 1865, however, the idea of a reconstructed nation meant far more than just a restoration of southern participation in the government. The times seemed to demand a reconstructed Constitution, almost a “Second Founding” of the American republic with the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments (1865-70). It also meant more broadly a reconstructed multi-racial society, not only in the South but also in the North, one that now included free blacks and whites living and often voting together. That proved highly controversial, quite difficult and sometimes brutally violent. When he was 16-years-old, former Virginia slave Booker T. Washington traveled over 500 miles, mostly by foot, in order to receive an education at the Hampton Institute, one of several schools established for the freed people during the era of Reconstruction. In chapter 3 of his memoir, Up From Slavery, Washington recounts his penniless arrival in Richmond on his way to Hampton. In one of the most memorable scenes in American literature, he describes how he “crept under the sidewalk” and slept outside on his first night, exhausted and hungry, but still hopeful that he could “reconstruct” his life with a real education. After much hard work, Washington succeeded, but he still acknowledged the challenges that loomed so large in the 1870s, such as what he called the “Ku Klux period,” which he considered, “the darkest part of the Reconstruction days.” Ultimately, the federal government stopped enforcing the fight for equality and civil rights after 1877, sending the nation into a new era, one without chattel slavery but also, sadly, with a growing acceptance for color discrimination and segregation.

Discussion Question

- What should have been the most urgent priorities for “reconstruction” after the Civil War?

Prince Rivers (c. 1820 – 1887)

“Dat’s de reason I jine de soldier. I was gettin’ big wages in Beaufort, but I’d rather take less, and fight for de United States; for I believe the United States is now fightin’ for me, and for my people.” —Prince Rivers quoted by James Miller McKim, August 1862

“Now we sogers are men –men de first time in our lives. Now we can look our old masters in the face. They used to sell us and whip us, and we did not dare say one word. Now we ain’t afraid, if they meet us, to run the bayonet through them.” —attributed to Prince Rivers, November 4, 1863

“I was told that the Government has given Land to Soldiers. If this land were given will [it] be just for the time being or will [it] be hereafter held by the Soldiers? I would like very much to know if any Part of the Mainland. If so I would like to get a piece on Mr. H.M. Stuart plantation, Oak Point, near Coosaw River.” —Prince Rivers to Gen. Rufus Saxton, November 26, 1865

Additional resources from Emancipation Digital Classroom: