But even taking into account all the qualifications and exceptions, there is a clear pattern: constitutional amendments have not been an important means of changing the constitutional order. –Prof. David Strauss (University of Chicago Law School)

For a short summary of Strauss’s unconventional views on Article V, see this online post from the National Constitution Center. Then re-read his full article from Harvard Law review on our course syllabus.

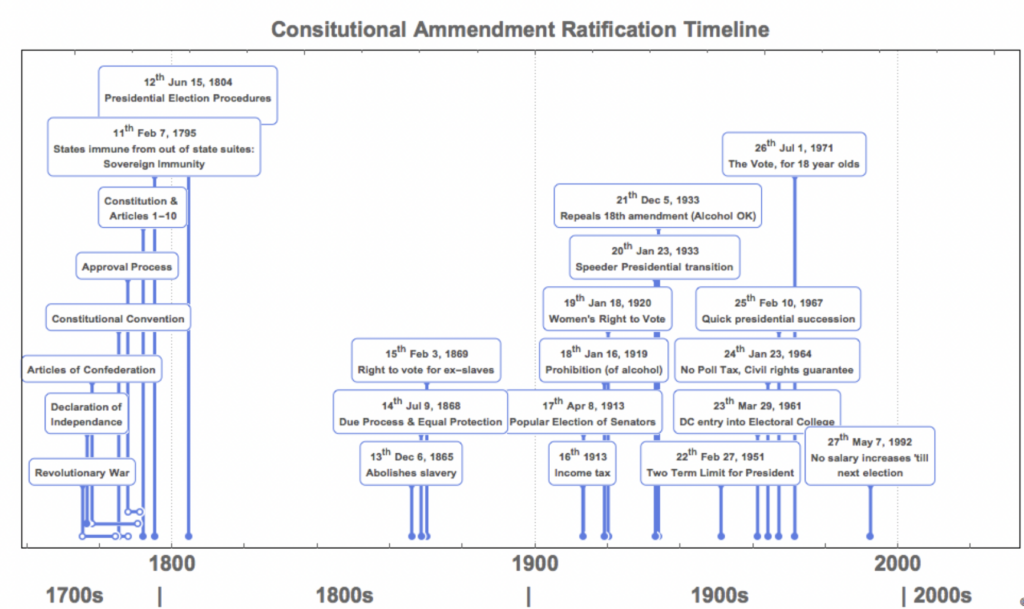

- What was the fastest timeline for amendment approval and ratification?

- What was the longest timeline for amendment approval and ratification?

How does the Constitution change? or what is the difference between the “Big C” and the “little c” constitution?

27 Amendments (1791 – 1992)

Article V

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.

Gregory Watson, Step-Father of the 27th Amendment

From Scott Bomboy, “How a College Term Paper Led to a Constitutional Amendment,” NCC blog:

Founding Father James Madison first proposed this amendment back in 1789 along with several other amendments that became the Bill of Rights, but it took 203 years for it to become the law of the land.

In 1982, a college undergraduate student, Gregory Watson, discovered that the proposed amendment could still be ratified and started a grassroots campaign. Watson was also an aide to Texas state senator Ric Williamson.

Shortly after the amendment was ratified a decade later, New York Law School professor Richard B. Bernstein traced the journey from 1789 to 1992 in a Fordham Law Review article. Bernstein called Watson the “step-father” of the 27th Amendment. Watson was a sophomore at the University of Texas-Austin in 1982 and he needed a topic for a government course. Watson researched what became the 27th Amendment and found that six states had ratified it by 1792, and then there was little activity about it.

Watson concluded that the amendment could still be ratified because Congress had never stipulated a time limit for states to consider it for ratification. Watson’s professor gave him a C for the paper, calling the whole idea a “dead letter” issue and saying it would never become part of the Constitution. “The professor gave me a C on the paper. When I protested she said I had not convinced her the amendment was still pending,” Watson told USA Today back in 1992. (In 2017, the university retroactively awarded Watson an A for his paper.)