By Anthony Scioscia

On Wednesday, September 17, 2014, Kate Martin had the distinct honor to visit Dickinson College in order to give the annual Winfield C. Cook Constitution Day Address. Martin’s lecture was entitled “Government Surveillance and the Bill of Rights” and seemed to have the promise of a strong argument against the constitutionality of the NSA’s surveillance programs. Keeping in mind her background as a civil liberties lawyer, I found myself a tad disappointed that she choose to lay out her argument for and against the constitutionality of these programs. One of her most rousing points on which her speech was centered was her belief that we have yet to engage in the democratic debate necessary regarding the wide ranging surveillance capabilities of the NSA. She asserted that the American people need to ensure that these powers are used rightly against foreign threats and not domestically against American citizens. So can these security measures designed with the intent to keep us safe instead violate the liberties bestowed upon us by the first and fourth amendments of the constitution? The answer is, sadly, yes.

No one knew better the tenuous balance between liberty and security that Martin references more then James Madison, the author of the Federalist papers and strong advocate for civil liberties. Madison, when speaking on the subject, has said “The means of defence agst. foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home.” This notion has been further extenuated in our US diplomatic history class from the view of scholar Walter LaFeber, who has said that, “Nearly two centuries ago Madison worried that liberty at home might be lost because of danger, “real or pretended,” abroad.” (LaFeber, 717) Can this really be true? Has the government ever used a crisis before to take away my rights as a citizen? The answer again, is yes; history tells us so.

In the late 1790’s in the wake of the XYZ affair, Congress used the crisis with France and a level of public upheaval to push through many of their highly sought political policies. One such policy was the highly controversial Sedition Act which stated that anyone speaking to defame the government whose words were found to be untrue by a jury could be convicted of seditious libel. As chronicled by George C. Herring, “the Federalist passed several vaguely worded and blatantly repressive Sedition Acts that made it a federal crime to interfere with the operation of government or publish any “false, scandalous and malicious writings” against its officials.” (Herring, 87) Although this law only lasted three years, it was the first example of the government encroaching on the liberties of the American people for security reasons.

Fast forward to 1972–almost two hundred years later–when the Supreme Court made the decision on the landmark Keith case, in which the court decided that the warrentless wiretaps that the government was conducting for domestic security issues were unconstitutional. Phone calls were not even protected under the fourth amendment until 1968 and up to this point, the government used wiretaps to conduct surveillance as they saw fit on any domestic persons. In the decision of this case, Justice Powell wrote “history has documented that government has viewed with suspicion those who most fervently oppose it’s policies.” He goes on to point out that political dissent by the people should not be under an unchecked surveillance power. He concludes his statement with the belief that these surveillance powers should not stop the people from speaking in a negative manner about the government in a private conversation. These wiretaps raised the questions of who was really being targeted and for what purposes?

The Church and Pike committees were congressional efforts to analyze and report on intelligence agencies since the dawn of the Cold War. The conclusions of their findings were startling, as they unearthed a history of domestic spying. The scope of this spying ranged from surveillance on the civil rights activists, the Vietnam war protesters, and journalists. The government justified their actions by stating there was a threat of foreign influence with these domestic activities. This was the first evidence we have that the government was using surveillance to monitor political dissent.

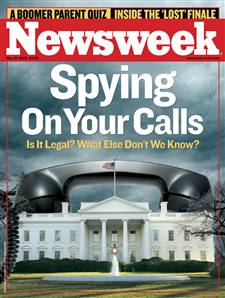

Where do we stand today in the aftermath of 9/11? With this historical context in mind, are we headed to a full blown police state where individual liberties are at a minimum? That is hard to say. It is likely that the mechanisms are in place for the creation of a police state under FISA law, which allows for the government to have access to public meta data through cell phone companies. Public meta data encompasses emails, call logs, duration of phone calls, and to whom they were placed as long as one end of the communication is centered abroad.

As we have reached a point in the 21st century where technology has progressed so far that the government has the surveillance capabilities to monitor every aspect of our lives. The only checks on stopping full blown domestic surveillance are the governments dissgression and the rule of law. It is up to the American people to decide if this so called increase in security is worth is worth the potential infringement upon individual liberties, that history and Madison explicitly warns us of.

Leave a Reply