What lessons should policymakers learn from Woodrow Wilson?

CHAPTER 10: “A New Age”: Wilson, the Great War, and the Quest for a New World Order, 1913-1922

“Wilson towers above the landscape of modern American foreign policy like no other individual, the dominant personality, the seminal figure.” (Herring, p. 379)

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 379.

Making the World “Safe for Democracy”

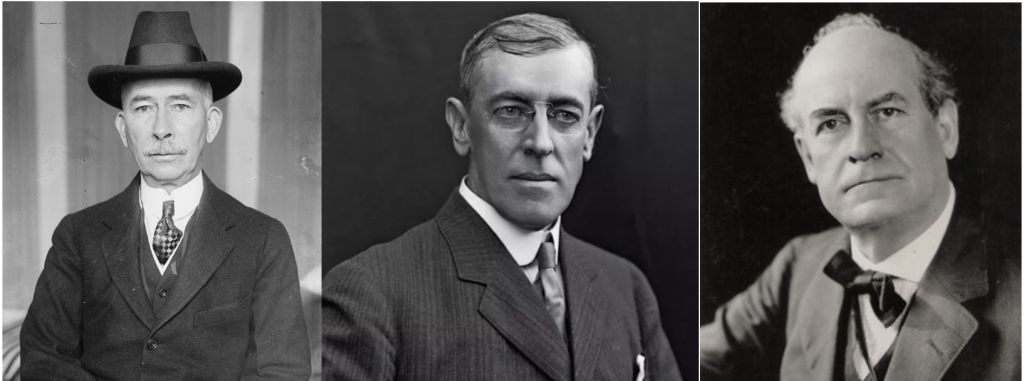

Wilson’s Foreign Policy Team

Defining the Wilsonian Foreign Policy Landscape

“The Great War also sparked a debate over basic foreign policy principles that would rage until World War II and persist in modified form thereafter. Breaking with hallowed tradition, those who came to be called internationalists insisted that the American way of life could be preserved only through active, permanent involvement in world politics.” (Herring, p. 406)

- Conservative Internationalists

- Progressive Internationalists

- Isolationists

Wilsonianism in an Age of Revolution

“Wilson’s response to these revolutions revealed his good intentions and the difficulties of their implementation.” (Herring, p. 383)

- Mexico (1910)

- China (1911)

- Russia (1917)

Student-produced map for Coming of WWI (Imran Hasan)

KEY TERMS: Fourteen Points (1918) // Treaty of Versailles (1919)

Fourteen Points (1918)

“In a series of public statements, most notably in his Fourteen Points address of January 18, 1918, Wilson molded these broad principles into a peace program. Called by the New York Herald “one of the great documents in American history,” the speech responded to Lenin’s revelations of the Allied secret treaties dividing the spoils of war and his calls for an end to imperialism as well as a speech by Lloyd George setting out broad peace terms. Wilson sought to regain the initiative for the United States and rally Americans and Allied peoples behind his peace program. He called for ‘open covenants of peace, openly arrived at.’ He reiterated his commitment to arms limitations, freedom of the seas, and reduction of trade barriers. On colonial issues, to avoid alienating Allies, he sought a middle ground between the old-style imperialism of the secret treaties and Lenin’s call for an end to empire. He did not use the word self-determination, but he did insist that in dealing with colonial claims the ‘interests’ of colonial peoples should be taken into account, a marked departure from the status quo. He also set forth broad principles for European territorial settlements –a sharp break from the U.S. tradition of non-involvement in European affairs. The peoples of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires should be assured ‘an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.’ Belgium must be evacuated, territory formerly belonging to France restored. A ‘general association of nations’ must be established to preserve the peace.’” (George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 412)

Discussion Questions

- In this chapter, Herring paints a vivid portrait of Woodrow Wilson. How would you characterize Wilson’s leadership on foreign policy and global strategy?

- Do the Fourteen Points represent a general continuation or a fundamental departure from American foreign policy traditions?

Treaty of Versailles (1919)

“At the time and since, blame has been variously cast for the outcome of 1919-20 [when the US rejected the Treaty of Versailles]. Lodge and the Republicans have been charged with rabid partisanship and a deep-seated personal animus that fueled a determination to embarrass Wilson. It can be argued, on the other hand, that they were simply doing the job the political system assigned to the ‘loyal’ opposition and that the Lodge reservations were necessary to protect national sovereignty. The Democrats have been criticized for standing firmly –and foolishly– with their ailing leader, instead of working with Republicans to gain a modified commitment to the League of Nations. Wilson himself has been accused of the ‘supreme infanticide,’ slaying his own brainchild through his stubborn refusal to deal with the opposition….The defeat of Wilson’s handiwork leaves haunting if ultimately unanswerable questions. The Wilson of 1919-20 believed that vital principles were at stake in the struggle with Lodge and that compromise would render the League of Nation all but useless. Would a more robust and healthy Wilson –the artful politician of his first term– have built more solid support for his proposals or found a middle ground that would have made possible Senate approval of the treaty and U.S. entry into the League of Nations? Could a modified League with U.S. participation have changed the history of the next two decades?” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 433-34

Defining the Treaty Debate Landscape (1919-20)

“Greater challenges awaited in Paris, where the peace conference opened on January 12, 1919. In heading the U.S. delegation himself, Wilson broke precedent, becoming the first president to go to Europe while in office and personally to conduct major negotiations. He remained abroad for more than six months, with only a two-week interlude in the United States, suggesting the extent to which foreign relations now dominated his agenda.” (Herring, p. 417)

“It was a fiercely partisan battle. There was no tradition in U.S. politics of bipartisanship on major foreign policy issues. On the contrary, since the Jay Treaty in 1794, parties had fought bitterly over such matters.” (Herring, p. 427)

- Reservationists

- Wilsonians

- Irreconciliables

Treaty of Versailles votes:

- November 18, 1919 — 38 – 55 for treaty with reservations

- November 19, 1919 –38 – 53 for Wilson’s treaty

- March 19, 1920 — 49 – 35 for Wilson’s treaty // (56 required for 2/3 super-majority)

Discussion Questions

- Lodge and Wilson were both internationalists. So why did they destroy the greatest accomplishment of American internationalism to that point in time?

- Does this American treaty-making and treaty-ratifying system deserve any blame for this tragic outcome?