“With a strong dose of idealism and more than a smattering of genuine goodwill, the Good Neighbor policy in its initial stage terminated existing military occupations and disavowed the US right of military intervention without relinquishing its preeminent positions in the hemisphere and dominant role in Central America and the Caribbean.” Herring, From Colony, [529].

Nelson A. Rockefeller, head of the Office for the Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics. Image Courtesy of the Office for Emergency Management; Royden Dixon, photographer – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3b06388.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work.

In the 1930s following the first World War, the United States began a phase of isolationist diplomacy. Tied into this drive for isolation was a new attitude of non-intervention in Latin America. The “Good Neighbor” policy as it came to be known, was intended to curb German influence in the region. In August of 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) appointed Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller as the head of the Office for the Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics.[1] Rockefeller’s experiences in the region due to his business interests caused him to see the need for improved economic and political relations between the U.S. and Latin America. This drive for better business coupled with the fear of German influence in the region drove Rockefeller under his new-found title with the U.S. government to take on the task of creating a new, enticing image for the U.S. in the region. What the State Department would later describe as “the greatest outpouring of propagandistic material by a state ever”, was one of the most successful ventures in public diplomacy.[2]

Nelson Rockefeller, the second son to Rockefeller Jr., began his fascination with Latin America in early 1930s when he became the director of Creole Petroleum Company (a Standard Oil affiliate) which extracted the majority of its foreign oil from the Lake Maracaibo region of Venezuela. Through his work he made several extended trips to Venezuela in 1937 and 1939. During these he experienced local contempt towards his presence in reaction to what the population felt was a symbol of American imperialism.[3] Rockefeller also would travel to Mexico in 1939 following the nationalization of U.S. oil companies in the country where he would see, again firsthand, the need for improved public relations between the U.S. and its southern counterparts.[4] These experiences as a business man, coupled with the influence of his peer group at the time (Beardsley Ruml, Wallace Harrison, Jay Crane, William Benton), came to the conclusion that something must be done to strengthen relations with Latin America.

In the Spring of 1940 Rockefeller, with the help of Ruml, sent a memorandum to Roosevelt detailing what he and his colleagues saw as a decline in the U.S.’s economic and political prowess in the hemisphere. It detailed the need for protection against the potential influence of Axis powers in Latin America.[5] They pointed out the shortcomings of the State Department and presented the idea of an independent government agency that could more rapidly take action.[6] Come August, Nelson would be appointed into his position as head of the Office for the Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics, which changed names several times when it became the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), then again when it was shortened to the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA). Despite these changes, throughout its operations it consistently held the nickname as the Rockefeller Office.

The official job of the Rockefeller Office, as outlined by FDR, would be to “coordinate the activities of the government with respect to hemispheric defense” by pressuring the “Latin American countries into cutting off their trade with Axis powers”.[7] Concealed within its main purpose of propagandizing for the U.S., the office created the first government information program in the region which fed intelligence on the political and economic events to the U.S..[8] A key underlying assumption was made in the creation of this new execution of foreign relations that, “mass communication research could and should serve domestic and foreign policy purposes” and that therefore the “gathering of information about Axis activities, attitudes towards the United States, and communication habits in Latin America” must be conducted.[9] Rockefeller undertook these missions and executed the propaganda campaign with skill and tact.

At its conception, the Rockefeller Office was appropriated $140 million to be spent over a five-year term.[10] Rockefeller quickly put his influence and economic brains to work. To help his cause, he acquired a ruling from the U.S. Department of Treasury allowing American corporations that were willing to work with the Rockefeller Office in generating pro-American content to be exempt from the cost of advertisements they published in Latin America.[11] To stunt news from anti-American or pro-German sources the Rockefeller Office only supplied the precious commodity of newsprint to local newspapers that published articles and advertisements in line with the U.S. new friendly image.[12] The highly successful En guardia magazine which was produced by the Rockefeller Office was distributed throughout Latin America.[13] Similarly his office sponsored cultural demonstrations of Americana such as the NBC Symphony in 1940.[14] This included speakers who advocated for the Allied side such as the tour by anti-fascist Arturo Toscanini in the East Coast of Latin America.[15]

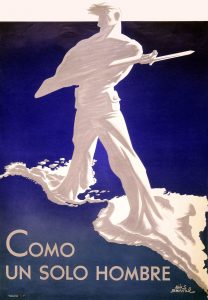

Good Neighbor Policy propaganda posters appealing to the idea of the American Republics developing closer bonds. Image courtesy of: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Office_of_the_Coordinator_of_Inter-American_Affairs#/media/File:OCIAA-Como-Un-Solo-Hombre-Poster.jpg

A significant tool that was developed through Rockefeller’s propaganda campaign was the development of finding ways to measure the success of this new public diplomacy through polling public opinion. To do this, Rockefeller contracted Dr. George Gallup to “conduct public opinion surveys in the countries below the Rio Grande”.[16] Brazil was selected to be the first country surveyed. The research was pitched to Rockefeller as a “Public Opinion Study” that would analyze “totalitarian propaganda techniques in South America”.[17] On August 24th 1940 FDR allocated $2,000,000 dollars to the U.S. Cultural Relations program, the official research then took place February through May of 1941.[18] Though at the time the State Department was reticent to accept the findings of these polls, the Brazilian study provided the first template on getting a measure of public diplomacy campaign’s success in a region.

In conjunction with his successful aid for pro-American sentiment, Rockefeller also played a role in helping to stifle Italian- and German-owned airlines operating in Latin America.[19] He also advocated for remedying the problems of disease, illiteracy, and under-production of food, things he saw as elements undercutting the potential for supporting democracy. In response to a memo Rockefeller sent to FDR on the matter, the Institute of Inter-American Affairs was set up as a joint project between the United States and Latin American governments.[20]

Rockefeller, under his appointed duties from FDR, executed an incredibly successful venture in public diplomacy that was seen as crucial to the assurance of Latin America siding with the Allied powers. Through the four pillars of public diplomacy; advocacy, Americana, mutual understanding, and advising Washington policymakers on the significance and implications of events in Latin America, Rockefeller was able to cultivate stronger relationships between the U.S. and Latin American countries. This priority and policy of non-intervention ended with the start of the Cold War. The U.S. would go on to fight Soviet influence through intervention (via hard power through covert action) rather than the previously employed campaign of successful public diplomacy. The legacy that the Rockefeller Office leaves behind is one that shows that persuasion can successfully be effected by investing in a public diplomacy campaign.

Notes:

[1] George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), [529].

[2] Herring, From Colony, [529].

[3] “Nelson A. Rockefeller,” The North American Congress on Latin America, [1], https://nacla.org/article/nelson-rockefeller.

[4] “Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

[5] Helen Fuller, “Young Nelson Rockefeller.” New Republic [9]

[6] Fuller, “Young Nelson Rockefeller” [9]

[7] “Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

[8] “Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

[9] Ortiz-Garza, Jose Luis. “The First Scientific Mass Communications Research in Latin America: The Brazilian Survey, February-May 1941.” Conference Papers — International Communication Association

[10] “Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

[11] Edward Jay Epstein, “Rockefellers,” accessed April 9, 2017, http://edwardjayepstein.com/rockefellers/chap5.htm.

[12] Epstein, “Rockefellers”

[13]Herring, From Colony, [529].

[14]Herring, From Colony, [529].

[15]Herring, From Colony, [529].

[16] Ortiz-Garza, Jose Luis. “The First Scientific Mass Communications Research in Latin America: The Brazilian Survey, February-May 1941.” [4]

[17] Ortiz-Garza, “The First Scientific Mass Communications Research in Latin America: The Brazilian Survey, February-May 1941.” [5]

[18] Ortiz-Garza, “The First Scientific Mass Communications Research in Latin America: The Brazilian Survey, February-May 1941.” [5]

[19]“Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

[20]“Nelson A. Rockefeller,” [1].

Bibliography:

Epstein, Edward Jay. “Rockefellers.” Accessed April 9, 2017. http://edwardjayepstein.com/rockefellers/chap5.htm.

Fuller, Helen. “Young Nelson Rockefeller.” New Republic 113, no. 1 (July 2, 1945): 9. Publisher Provided Full Text Searching File, EBSCOhost (accessed April 5, 2017).

Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

“Nelson A. Rockefeller.” The North American Congress on Latin America. https://nacla.org/article/nelson-rockefeller.

Ortiz-Garza, Jose Luis. “The First Scientific Mass Communications Research in Latin America: The Brazilian Survey, February-May 1941.” Conference Papers — International Communication Association (2009 Annual Meeting 2009): 1-12. Communication & Mass Media Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed April 5, 2017).