By Emilia McManus

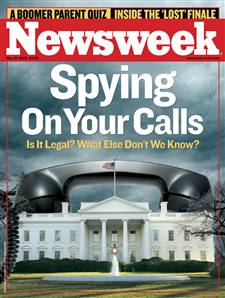

As Kate Martin pointed out in her Constitution Day address last week at the Clarke Forum, the dialogue about liberty and national security is as old as our country itself. Many of the actions taken by early presidents created precedents that paved the way for the national security debate we face today. Ms. Martin sketched a path through history to illustrate the development of this conversation. She began by describing the legal limits set out in the Constitution and by Congress to protect privacy, starting with the 4th amendment and ending with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA). FISA is the current legislation that governs the NSA. Ms. Martin also discussed the Supreme Court’s role in expanding executive authority in the arena of foreign policy. In US v. Curtiss-Wright (1936), the court describes the executive branch as the sole conductor of international relations. Since then, it has been read as giving the President the authority to do whatever necessary to protect national security.

In his article “The Constitution and United States Foreign Policy: An Interpretation,” Walter LaFeber characterized the turn of the 20th century as a time of “imperial presidencies, weak congresses, and cautious courts” (LaFeber 696). This is not dissimilar to the position we find ourselves in today. Ms. Martin’s main point of contention with federal surveillance was not necessarily due to the threat it poses to our right to privacy, but rather that it was done clandestinely without the opportunity for public debate.

Foreign and domestic policy have always been linked. The United States faced a number of existential threats in its early years. During its undeclared Quasi-War with France in 1798, the Federalist-controlled Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. Although it was intended to protect national security by mitigating the threat of French influence in Congress, it was decried as a “reign of witches” by Thomas Jefferson and seen as an attempt to suppress anti-Federalist voters (Herring 87). One of Ms. Martin’s chief concerns with the NSA is the threat it poses to both private and public dissent. The Seditious Libel Act was regarded as a similar threat. It parallels the discussion today in that it was a response to a very real threat. Ms. Martin was fairly excoriating with regards to the NSA programs. One of her critiques was that that although frequently there are more narrowly tailored potential responses to security threats, there is no mechanism in place to force the government to choose those options. However, while she described the purported mutual exclusivity of liberty and national security as a false dichotomy used as inflammatory rhetoric, she failed to provide alternate solutions or make a case in favor of the NSA as she purported to do at the outset of her talk.

In general, Ms. Martin’s talk provided a comprehensive overview of the development of the debate over privacy and national security. However, she could have done more to elaborate on how the changing global landscape necessitates new approaches to national security. She presented a convincing case against government surveillance but neglected to address measures the government could take to deal with terrorism that do not infringe upon the liberty of its citizens or damage the integrity of the democratic process.