Were Jeffersonians consistent in their diplomatic decision-making during the early 1800s?

CHAPTER 3: “Purified, as by Fire”: Republicanism Imperiled and Reaffirmed, 1801-1815

“No one personifies better than Thomas Jefferson the essential elements of a distinctively American approach to foreign policy.”

–The opening line from chapter 3 of George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 93.

- KEY TERMS & FIGURES: Louisiana Purchase (1803) // War of 1812 // Thomas Jefferson

Jeffersonian Era Timeline

1801 // Inaugural Address

- “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

- “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none…”

1801-05 // Tripolitan War

- Jefferson had once proclaimed in 1785 regarding the Barbary pirates: “I think it is to our interest to punish the first insult because an insult

unpunished is the parent of many others.” (Herring, 99)

- Herring describes the conflict in North Africa as “America’s first foreign war and the first of numerous intrusions into a region that, more than two centuries later, remained terra incognita for most Americans” (Herring, 97-8)

1803 // Louisiana Purchase

- Special envoy James Monroe negotiates purchase of Louisiana Territory from France (approximately 287,000 acres or 827,000 square miles) for $15 million

- Historian Robert Lee estimates the real cost of the acquisition was closer to $2.6 billion (or $8.5 billion adjusted for inflation) and occurred over 222 Indian cessions or additional agreements between 1804 and 1970

1804 // Jefferson refuses to recognize independent Republic of Haiti

- The US would not establish diplomatic relations with Haiti until 1862 under the Lincoln administration

1804 // Mobile Act and the Pursuit of West Florida

- “Jefferson’s Florida diplomacy reveals him at his worst. His lust for land trumped his concern for principle and obscured his usually clear vision.” (Herring, 110)

1807 // British attack on the USS Chesapeake

- According to Jefferson, “This country has never been in such a state of excitement since the battle of Lexington.” (Herring, 118)

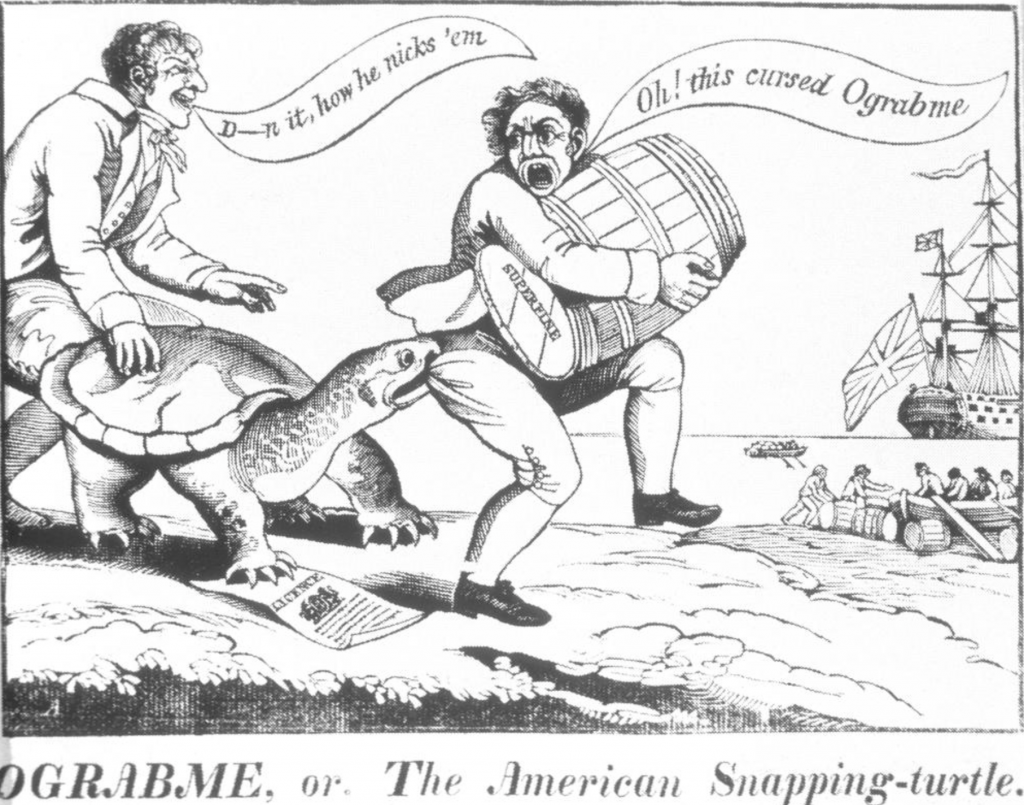

- Americans respond by imposing an embargo on all foreign trade, employing what Jefferson labeled “peaceable coercion” to protect American interests (Herring, 119)

1808-09 // Jefferson administration pushes for tougher enforcement of embargo against smuggling coming from New England

- “The passage in January 1809 of additional enforcement measures sharply circumscribing individual liberties did not stop smuggling and provoked near-rebellion in New England. Angry crowds revived songs of protest from the revolution….There was open talk of secession.” (Herring, 120)

1809 // Congress adopts new non-intercourse act

- Replaces general trade embargo with targeted boycott against Britain and France

Political cartoon against embargo policy (c. 1807-11 by Alexander Anderson). Can you decipher some of its text and symbolism?

Louisiana Purchase (1803)

“By any standard, the Louisiana Purchase was a monumental achievement. The nation acquired 287,000 acres, doubling its territory at a cost of roughly fifteen cents per acre, one of history’s greatest real estate steals. Control of the Mississippi would tie the West firmly to the Union, enhance U.S. security, and provide enormous commercial advantages. Napoleon’s sale of Louisiana all but eliminated a French return to North America, leaving the Floridas hopelessly vulnerable and Texas exposed. The United States’ acquisition of Louisiana established a precedent for expansion and empire and gave substance to the idea that would later be called Manifest Destiny.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 107

Discussion Questions

- Herring describes Thomas Jefferson as a “practical idealist.” Does the story behind the Louisiana Purchase embody this description? What about afterwards, as President Jefferson pivoted toward the acquisition of Spanish Florida?

- Jefferson’s approach to expansionism and other foreign policy matters represented something of a departure from his predecessors. How did he try to change both the nation’s diplomatic strategy and also diplomatic style as president?

Additional Resources

- Summary & Context (Jefferson’s Monticello)

- Robert Lee, “The True Cost of the Louisiana Purchase,” Slate, March 1, 2017

War of 1812 (1812-1815)

“Madison accepted war in 1812 in the confidence that it would be relatively short, inexpensive, and bloodless –more talk than fight– and that the United States could achieve its objectives without great difficulty. In fact, the War of 1812 lasted two and a half years and cost more than two thousand American lives and $158 billion. For Britain, the war was a military and diplomatic sideshow to the main performance in Europe; for the United States, it became a struggle for survival.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 127

Discussion Questions

- How did Jefferson’s attempts to embargo Britain during his second term undermine his presidency and cloud his foreign policy legacy?

- The War of 1812 is a misnomer in several ways. Not only was it a nearly three-year conflict, but also the war involved far more than just the US and British. What was the role of various Indian nations in this pivotal conflict? How did the outcome of the war reshape US-Native American relations after 1815?

Additional Resources

- War of 1812 documents (Avalon Project)

- Chapter on Early Republic (American Yawp, online textbook)

- War of 1812: Perspectives (PBS)

- Star Spangled Banner (CNN / annotated lyrics)

KEY FIGURES

Thomas Jefferson: Practical idealist?

“Jefferson was also a ‘practical idealist’ (often more practical than idealistic), and in this too he set an enduring tone for his nation’s foreign policy. His invocation of principle masked grandiose ambitions.” (Herring 93)

The Meaning of “Pell-Mell”

“Outraged when received by the president in a tattered bathrobe and slippers and forced at a presidential dinner to conform to ‘pell-mell’ seating arrangements respecting of rank, the British minister to Washington, Anthony Merry, bitterly protested the affront suffered at the president’s table. Jefferson no doubt privately chuckled at the arrogant Englishman’s discomfiture, but his subsequent codification of republican practices into established procedures betrayed a larger purpose.” (Herring, 96)

- In 2007, writing for The Atlantic magazine, novelist Tom Wolfe went so far as to claim that “the idea of America” was actually born at that moment, Friday evening, December 2, 1803, when the British ambassador Merry first confronted “pell-mell.” Read more about it here.

Other Key Players, Witnesses, or Examples

- John Jacob Astor

- George Mathews