Should Franklin Roosevelt have confronted the isolationists sooner?

CHAPTER 12: The Great Transformation: Depression, Isolationism, and War, 1931-1941

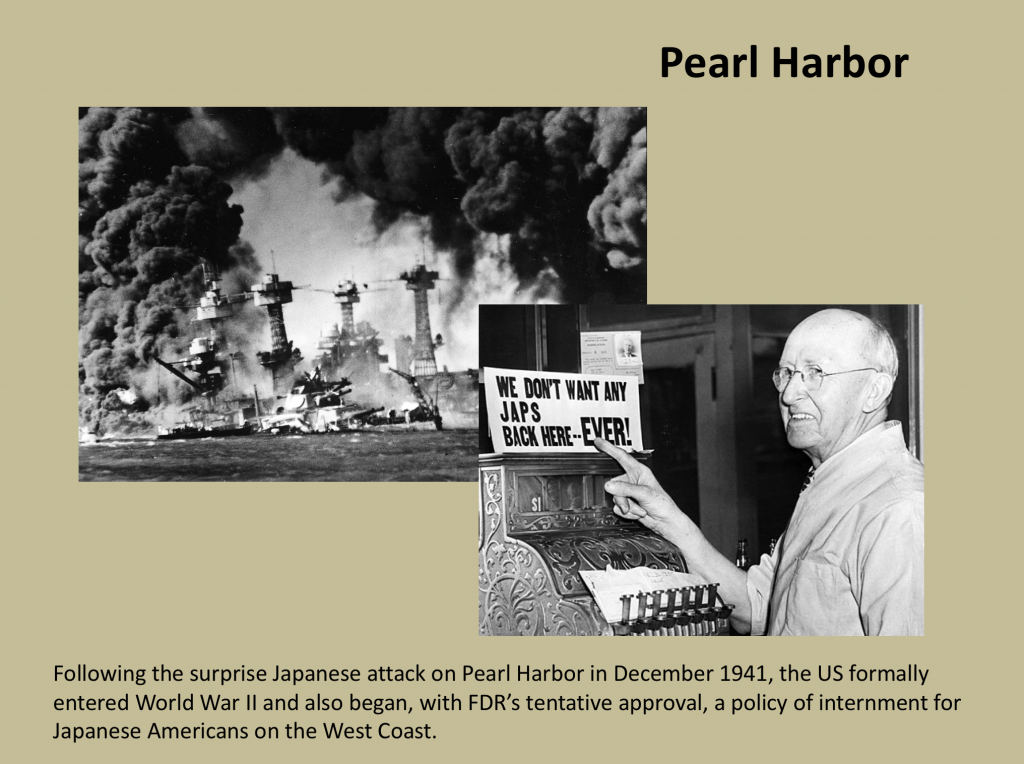

“The years from 1931 to 1941 brought major changes in U.S. foreign policy. Responding to the Great Depression and the threat of a new world war, Americans in the mid-1930s embraced isolationist attitudes and endorsed neutrality policies that in the event of war called for the sacrifice of traditional neutral rights for which the nation had fought in 1812 and 1917. The Munich Conference and especially the fall of France produced another reversal. Many anxious Americans now concluded that their values and interests were threatened by events abroad and that their security required them to assist nations combating the Axis menace even at the risk of war. Franklin Roosevelt took the lead in educating Americans to this new perspective on world affairs. He has been criticized for his timidity in responding to World War II and for underestimating his powers of persuasion. But he had vivid memories of Wilson’s defeat and feared getting too far out in front of public opinion.”

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 536-37.

KEY TERMS: Good Neighbor Policy (1933) // America First Committee (1940)

Good Neighbor (1933)

“The one sentence of FDR’s inaugural address devoted to foreign policy included that memorable if also notably vague line ‘In the field of world policy I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor.’ Meant to apply generally, it became identified with the Western Hemisphere and was one of Roosevelt’s most important legacies. A product of self-interest and expediency along with a strong dose of idealism and more than a smattering of genuine goodwill, the Good Neighbor policy in its initial stage terminated existing military occupations and disavowed the U.S. right of military intervention without relinquishing its preeminent position in the hemisphere and dominant role in Central America and the Caribbean. In time, it extended beyond policy into the realm of cultural interchange.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 497

Discussion Questions

- How did Herbert Hoover lay the “foundations” for the Good Neighbor policy and why was that such a departure from previous US involvement in Latin America?

- What were some of the cultural interchanges of the Good Neighbor policy?

Student-produced map (George Gilbert)

America First Committee (1940)

“Pressure groups also spearheaded the opposition. In July [1940], Yale University students and midwestern businessmen formed the America First Committee. As the name suggests, America Firsters ardently opposed intervention –and aid to Britain, which, they argued, would inevitably lead to intervention. They saw the war not as a great ideological conflict but as another round in the endless struggle among Europeans for power and empire. The United States, they insisted, had no stake in that conflict. Some like aviator hero Charles Lindbergh preached accommodation with Hitler. Others minimized the German threat and advocated defense of the Western Hemisphere. America First was an unwieldy coalition of strange bedfellows, businessmen, old progressives and leftists, and some strongly anti-Jewish groups. Many blamed Roosevelt’s interventionist policies on a personal lust for power. These various groups created local and regional offices, organized rallies, sent out mailings, and propagandized Congress.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 521-22.

Discussion Questions

- What was the essential context behind the strong anti-war movement in the late 1930s and early 1940s?

- How did FDR overcome the opposition of America First and general isolationist sentiment to secure Lend-Lease aid for Great Britain (and later the Soviet Union)?