Were Progressive era American diplomats more harmful than helpful in promoting global peace and prosperity?

CHAPTER 9: “Bursting with Good Intentions”: The United States in World Affairs, 1901-1913

“The United States between 1901 and 1913 did take a much more active role in the world. Brimming over with optimism and exuberance, their traditional certainty of their virtue now combined with a newfound power and status, Americans firmly believed that their ideals and institutions were the way of the future. Private individuals and organizations, often working with government, took a major role in meeting natural disasters across the world. Americans assumed leadership in promoting world peace. They began to press their own government and others to protect human rights in countries where they were threatened. The perfect example of the nation’s mood in the new century, Roosevelt promoted what he called ‘civilization’ through such diverse ventures as building the Panama Canal, managing the nation’s imperial holdings in the Philippines and the Caribbean, and even mediating great-power disputes and wars. ‘We are today bursting with good intentions,’ journalist E.L. Godkin proclaimed in 1899.”

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 337-38.

Timeline

The internationalization of America and the Americanization of the world was under way by 1900. –Herring, p. 341

- 1901 // McKinley assassinated // TR becomes president AND Supreme Court Insular Cases

- 1903 // Root reforms begin to modernize US national security & Panama Canal treaty

- 1904-5 // Russo-Japanese War and US mediation and Roosevelt Corollary

- 1905 // Chinese American led boycott of US goods

- 1906 // American Jewish Committee forms to protest Russian pogroms

- 1907 // Gentleman’s Agreement with Japan // Second Hague conference

- 1914 // Panama Canal completed

- 1916 // Jones Act promises independence for Philippines

KEY PLAYERS

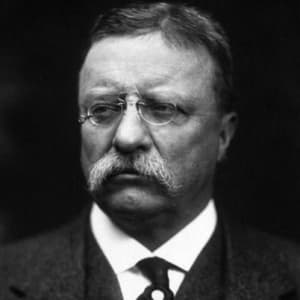

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919)

“Although thrust into office by an assassin’s bullet, Theodore Roosevelt perfectly fitted early twentieth-century America. He had traveled through Europe and the Middle East as a young man, broadening his horizons and expanding his views of other peoples and nations. An avid reader and prolific writer, he was abreast of the major intellectual currents of his day and had close ties to the international literary and political elite. From his early years, he had taken a keen interest in world affairs. He was a driving force behind, as well as an active participant in, the ‘large policy’ of the 1890s. In his first address to Congress, in December 1901, he preached the gospel of international noblesse oblige: ‘Whether we desire it or not, we must henceforth recognize that we have international duties no less than international rights.'” (Herring, chap. 9, pp. 344-45)

“Although thrust into office by an assassin’s bullet, Theodore Roosevelt perfectly fitted early twentieth-century America. He had traveled through Europe and the Middle East as a young man, broadening his horizons and expanding his views of other peoples and nations. An avid reader and prolific writer, he was abreast of the major intellectual currents of his day and had close ties to the international literary and political elite. From his early years, he had taken a keen interest in world affairs. He was a driving force behind, as well as an active participant in, the ‘large policy’ of the 1890s. In his first address to Congress, in December 1901, he preached the gospel of international noblesse oblige: ‘Whether we desire it or not, we must henceforth recognize that we have international duties no less than international rights.'” (Herring, chap. 9, pp. 344-45)

VS

Elihu Root (1845-1937)

“Almost as important [as President Theodore Roosevelt], if much less visible, was Elihu Root, who served Roosevelt ably as secretary of war and of state. A classic workaholic, Root rose to the top echelons of New York corporate law and the Republican Party by virtue of a prodigious memory, mastery of detail, and the clarity and force of his argument. A staunch conservative, he profoundly distrusted democracy. He sought to promote order through the extension of law, the application of knowledge, and the use of government. He shared Roosevelt’s internationalism and was especially committed to promoting an open and prosperous world economy. He was more cautious in the exercise of power than his sometimes impulsive boss. For entirely practical reasons, he was also more sensitive to the feelings of other nations, especially potential trading partners. A man of great charm and wit –when the 325-pound Taft sent him a long report of a grueling horseback ride in the Philippines’ heat, he responded tersely, ‘How’s the horse?’ –he sometimes smooth over his boss’s rough edges. He was a consummate state-builder who used his understanding of power and his formidable persuasiveness to build a strong national government. He was the organization man in the organizational society, ‘the spring in the machine,’ as Henry Adams put it. He founded the eastern foreign policy establishment, that informal network connecting Wall Street, Washington, the large foundations, and the prestigious social clubs, which directed U.S. foreign policy through much of the twentieth century. (Herring, chap. 9, p. 348)

“Almost as important [as President Theodore Roosevelt], if much less visible, was Elihu Root, who served Roosevelt ably as secretary of war and of state. A classic workaholic, Root rose to the top echelons of New York corporate law and the Republican Party by virtue of a prodigious memory, mastery of detail, and the clarity and force of his argument. A staunch conservative, he profoundly distrusted democracy. He sought to promote order through the extension of law, the application of knowledge, and the use of government. He shared Roosevelt’s internationalism and was especially committed to promoting an open and prosperous world economy. He was more cautious in the exercise of power than his sometimes impulsive boss. For entirely practical reasons, he was also more sensitive to the feelings of other nations, especially potential trading partners. A man of great charm and wit –when the 325-pound Taft sent him a long report of a grueling horseback ride in the Philippines’ heat, he responded tersely, ‘How’s the horse?’ –he sometimes smooth over his boss’s rough edges. He was a consummate state-builder who used his understanding of power and his formidable persuasiveness to build a strong national government. He was the organization man in the organizational society, ‘the spring in the machine,’ as Henry Adams put it. He founded the eastern foreign policy establishment, that informal network connecting Wall Street, Washington, the large foundations, and the prestigious social clubs, which directed U.S. foreign policy through much of the twentieth century. (Herring, chap. 9, p. 348)

KEY TERMS: Panama Canal (1903-14) // Dollar Diplomacy (1909-13)

Panama Canal (1903-14)

“Determined to complete the transaction before real Panamanians could get to Washington, [Philippe Bunau-Varilla] negotiated a treaty drafted by Hay with his assistance and far more favorable to the United States than the one Colombia had rejected. The United States got complete sovereignty in perpetuity over a zone ten miles wide. Panama gained the same payment promised Colombia. More important for the short run, it got a U.S. promise of protection for its newly won independence. Bunau-Varilla signed the treaty a mere four hours before the Panamanians stepped from the train in Washington. Nervous about its future and dependent on the United States, Panama approved the treaty without seeing it. Colombia, obviously, was the big loser. Panama got nominal independence and a modest stipend, but at the cost of a sizeable chunk of its territory, it’s most precious natural asset, and the mixed blessing of a U.S. protectorate. Panamanian gratitude soon turned to resentment against a deal Hay conceded was ‘vastly advantageous’ for the United States, ‘not so advantageous’ for Panama. TR vigorously defended his actions, and some scholars have exonerated him. Even by the low standards of his day, his insensitive and impulsive behavior toward Colombia is hard to defend. Root summed it up best. Following an impassioned Rooseveltian defense before the cabinet, the secretary of war retorted in the sexual allusions he seemed to favor: ‘You have shown that you have been accused of seduction and you have conclusively proven that you were guilty of rape.’ Although journalists criticized the president and Congress investigated, Americans generally agreed the noble ends justified the dubious means. Even before the completion of the project in 1914, the canal became a symbol of national pride. The United States succeeded where Europe had failed.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower (2008), pp. 368-9

Dollar Diplomacy (1909-13)

“[President] Taft and [Secretary of State] Knox adopted the Dominican model to develop a policy called ‘dollar diplomacy,’ which they applied mainly in Central America. They sought to eliminate European political and economic influence and through U.S. advisers promote political stability, fiscal responsibility, and economic development in a strategically important area, the ‘substitution of dollars for bullets,’ in Wilson’s words. United States bankers would float loans to be used to pay off European creditors. The loans in turn would provide the leverage for U.S. experts to modernize the backward economies left over from Spanish rule by imposing the gold standard based on the dollar, updating the tax structure and improving tax collection, efficiently and fairly managing the customs houses, and reforming budgets and tariffs. Taft and Knox first sought to implement dollar diplomacy by treaty. When the Senate balked and some Central American countries said no, they turned to what has been called ‘colonialism by contract,’ agreements worked out between private U.S. interests and foreign governments under the watchful eye of the State Department. Knox called the policy ‘benevolent supervision.’ One U.S. official insisted that the region must be made safe for investment and trade so that economic development could be ‘carried out without annoyance or molestation from the natives.’ These ambitious efforts to implement dollar diplomacy in Central America produced few agreements, little stability, and numerous military interventions.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower (2008), p. 373