Was American revolutionary era diplomacy truly revolutionary?

CHAPTER 1: “To Begin the World Over Again”: Foreign Policy and the Birth of the Republic, 1776-1788

“The Revolutionary generation held to an expansive vision, a certainty of their future greatness and destiny. They believed themselves a chosen people and brought to their interactions with others a certain self-righteousness and disdain for established practice. They saw themselves as harbingers of a new world order, creating forms of governance and commerce that would appeal to peoples everywhere and change the course of world history. ‘We have it in our power to begin the world over again,’ [Thomas] Paine wrote. Idealistic in their vision, in their actions Americans demonstrated a pragmatism born perhaps of necessity that helped ensure the success of their revolution and promulgation of the Constitution.”

“The Revolutionary generation held to an expansive vision, a certainty of their future greatness and destiny. They believed themselves a chosen people and brought to their interactions with others a certain self-righteousness and disdain for established practice. They saw themselves as harbingers of a new world order, creating forms of governance and commerce that would appeal to peoples everywhere and change the course of world history. ‘We have it in our power to begin the world over again,’ [Thomas] Paine wrote. Idealistic in their vision, in their actions Americans demonstrated a pragmatism born perhaps of necessity that helped ensure the success of their revolution and promulgation of the Constitution.”

–George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 12.

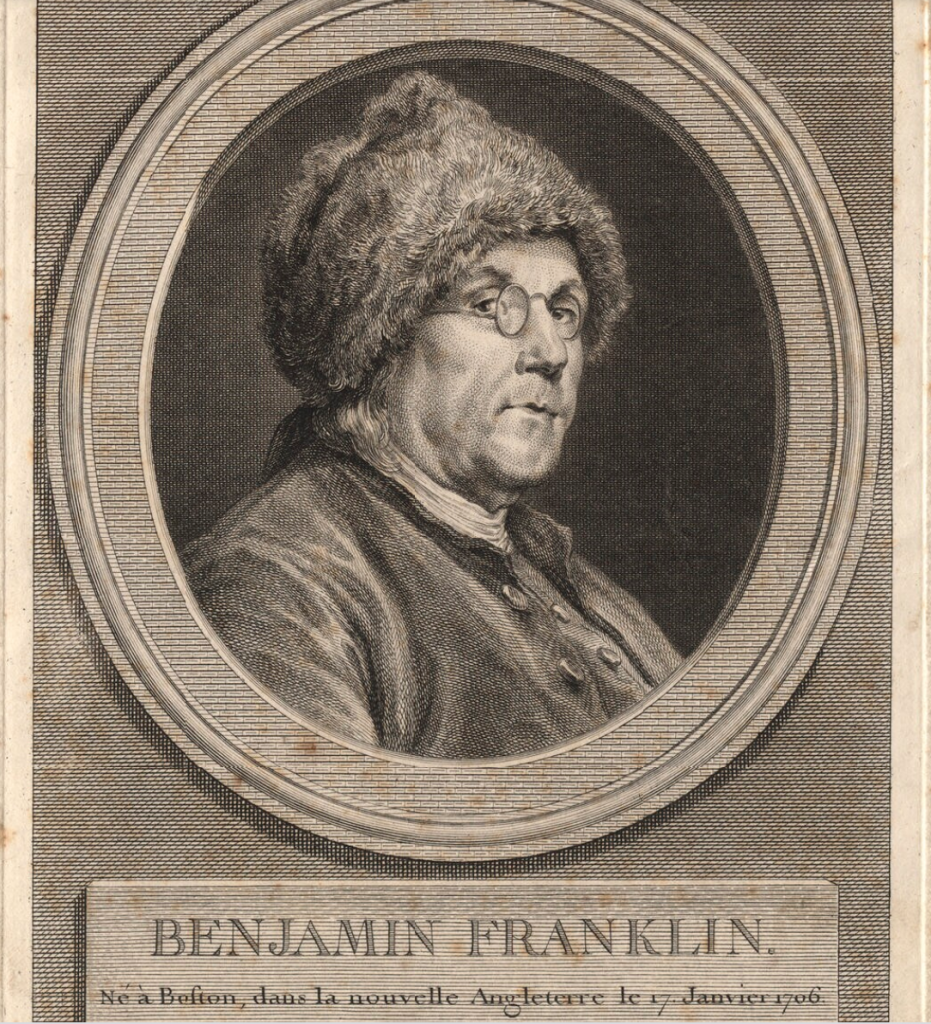

- KEY TERMS & FIGURES: US-French Alliance // Treaty of Paris // Benjamin Franklin

- Student Reflections (Fall 2020)

US-French Alliance (1778)

“Franklin’s mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America’s revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, p. 19

Discussion Question

- Why was the securing an alliance with France so vital to the success of the American Revolution? And yet how was it also a dangerous gambit?

Historians on Franklin’s “salon” diplomacy

Franklin’s headquarters in Paris

Franklin lived here, at what was known as the Hotel de Valentinois, in part of the Chaumont residence in Passy from 1777-1785. Today the address is 66 Rue Raynouard, Paris (Photograph courtesy of Graham Frater)

Additional Resources

- Model Treaty (1776)

- Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1778)

- Library of Congress webguide on US-French Alliance

- Benjamin Franklin Papers (LoC)

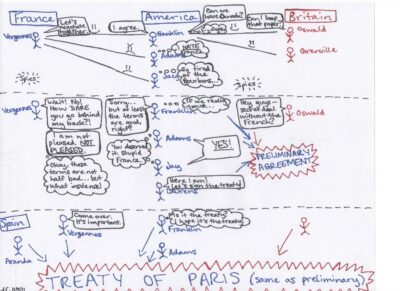

Treaty of Paris (1783)

Treaty of Paris (1783), unfinished portrait by Benjamin West (Maryland State Archives)

“The American negotiators have often been given credit for this favorable outcome [in the terms of the 1783 treaty]. They shrewdly played the Europeans against each other, it has been argued, exploiting their rivalries, wisely breaking congressional instructions, and properly deserting an unreliable France to defend their nation’s interests and maximize its gains. Such an interpretation is open to question. The Americans, probably from their own insecurities, were anxiety-ridden in dealing with ally and enemy alike. Jay’s excessive nervousness about England and then his separate approach to that country not only broke faith with a supportive if not entirely reliable ally but also delayed negotiations for several months. It eased pressure on Shelburne to make concessions and left the United States vulnerable to a possible Shelburne-Vergennes deal at its expense. Jay and Adams had reason to question Vergenne’s trustworthiness, but they should have informed him of the terms before springing the signed treaty upon him. Ultimately, the favorable settlement owed much less to America’s military prowess and diplomatic skills than to luck and change: Shelburne’s desperate need for peace to salvage his deteriorating political position and his determination to settle quickly with the United States and seek reconciliation through generosity.” –George Herring, From Colony to Superpower, pp. 32-3

Discussion Questions

- The paragraph above mentions four key individuals (two Americans, a Frenchman and an Englishman) and yet makes no mention of Franklin’s contribution to the Treaty of Paris. How would you characterize his role and what was his relationship like with those other four figures?

- As Herring indicates, American negotiators have traditionally been given enormous credit for achieving a major triumph in the treaty ending the American Revolution. Why? What was so impressive about the terms of the Treaty of Paris for Americans?

Image Gateways

Consider how painter Benjamin West portrayed the characters, personalities and relationships of the American delegation during the Treaty of Paris negotiations. And here are some other (less famous) visualizations of the power dynamics and issues at stake in the making of the 1783 peace treaty from previous History 282 students.

From Prerana Pakhrin:

From Anne Crowell:

KEY FIGURES

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

“Franklin’s mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America’s revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue. (Herring, chap 1, p. 19)

“Franklin’s mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America’s revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue. (Herring, chap 1, p. 19)

John Jay (1745-1829)

“One area of progress [under the Articles of Confederation] was in the administration of foreign affairs. [Robert] Livingston had repeatedly complained of inadequate authority and congressional interference. He resigned before the peace treaty was ratified. Congress responded by strengthening the position of the secretary of foreign affairs. John Jay assumed the office in December 1784 and held it until a new government took power in 1789, providing needed continuity. An able administrator, he insisted that his office have full responsibility for the nation’s diplomacy. Remarkably, he also conditioned his acceptance on Congress settling in New York. Assisted by four clerks and several part-time translators, he worked out of two rooms in a tavern near Congress’s meeting place. He did not achieve his major foreign policy goals, but he managed his department efficiently. Interestingly, a secret act of Congress authorized him to open and examine any letters going through the post office that might contain information endangering the ‘safety or interest of the United States.’ He appears not to have used this authority.” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 35-6)

“One area of progress [under the Articles of Confederation] was in the administration of foreign affairs. [Robert] Livingston had repeatedly complained of inadequate authority and congressional interference. He resigned before the peace treaty was ratified. Congress responded by strengthening the position of the secretary of foreign affairs. John Jay assumed the office in December 1784 and held it until a new government took power in 1789, providing needed continuity. An able administrator, he insisted that his office have full responsibility for the nation’s diplomacy. Remarkably, he also conditioned his acceptance on Congress settling in New York. Assisted by four clerks and several part-time translators, he worked out of two rooms in a tavern near Congress’s meeting place. He did not achieve his major foreign policy goals, but he managed his department efficiently. Interestingly, a secret act of Congress authorized him to open and examine any letters going through the post office that might contain information endangering the ‘safety or interest of the United States.’ He appears not to have used this authority.” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 35-6)

Other Key Players, Witnesses, or Examples

- John Adams

- Silas Deane

- Sarah Livingston Jay

- Thomas Jefferson

- Thomas Paine

- Elizabeth Willing Powel