By Riley Dickson (History 288: Civil War and Reconstruction, Spring 2015)

General Winfield Scott, the Commander of the Armies, assured the president on April 14th, 1861 that ““the capital can’t be taken, sir; it can’t be taken.” [1] Scott seemed to believe that a higher power would protect the capital from rebel forces. President Lincoln responded to Scott’s faith with cynicism, ““even if it has been ordained that the city of Washington will never be taken by the Southerners, what would we do, in case they made an attack upon the place, without men and heavy guns?” [2]

On April 14th, 1861 Fort Sumter was evacuated after a two-day siege. The bombardment, and subsequent surrender of the Fort in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina led President Lincoln to issue a proclamation on April 15, 1861. This executive order would have far reaching consequences that hastened the sectional divide between previously loyal southern states and the federal government. In Lincoln’s proclamation he admitted that the law “in the states of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas” was no longer enforceable by usual means. In order to restore the law in the southern states in rebellion Lincoln used his powers prescribed by the Militia Act of 1795 and called “seventy-five thousand” troops to restore federal power. [3]

First Page of Lincoln’s April 15, 1861 Proclamation. Courtesy of Senate.gov

The call for seventy-five thousand troops in the proclamation was and has been often criticized as being a half measure. Alexander J. Sessions, a Massachusetts clergyman, urged Lincoln to call for “half a million of troops” to put down the rebellion and protect Washington D.C. [4] A letter Lincoln received from Joseph Medill, of Chicago, also urged him to call up more volunteers in order to “crush the head of the rattle snake.” [5] Reproach for what many assumed was a limited call-up is not solely reserved for Lincoln’s contemporaries. The author Brian Holden Reid claims that Lincoln’s April 15th Proclamation indicated that “Lincoln expected the war to be a short police action.” [6]

The proclamation only called for seventy-five thousand men because that was the extent of Lincoln’s legal ability. The president only had the capability to call out a maximum of 75,000 militia from the States. [7] Therefore the criticism of Lincoln for his conservative call to arms from contemporaries and today is unfounded. In fact, according to the scholar Michael Burlingame, as the cabinet and the president constructed the proclamation they dealt with several legal issues including: “could the army and navy be expanded, unappropriated money be spent, Southern ports be blockaded, and the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus be suspended, all without Congressional approval?” [8] At the outset of the war, Lincoln used his war powers within the limits of pre-existing law.

Lincoln called on citizens to “aid” the endeavor of restoring the Union in anyway that they could support. His use of the word “loyal” was specifically directed at Unionists that were residents of states in rebellion. The verbiage of “facilitate” and “favor” was purposely pointed at loyal southerners because he didn’t expect them to join the militia that he was requesting. Simon Cameron, the Secretary of War, didn’t call-up any troops from the seceding states in his request for troops following the proclamation.

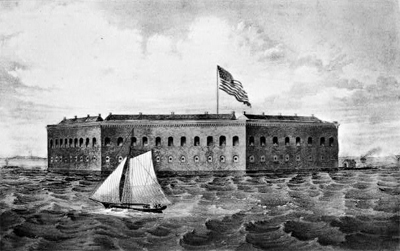

The proclamation laid out an initial strategy for the beginning of the war in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Fort Sumter. By the time of the proclamation most of the federal arsenals and forts within the Confederacy had been seized by the rebels. [9] The President was attempting to allay southern fears that a total war was going to be waged on the seceding territory and therefore publicly committed the new army to “reposes” captured federal property. He stated that the army would “avoid any devastation; any destruction of; or intereference with, property, or any disturbance of peaceful citizens, in any part of the country.”

Fort Sumter. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The president was so adamant about the preservation of property for non-combatants because of the question of the loyalty border states and Southern states that were still in the Union. At the time of the proclamation the Secession Convention of Virginia was meeting in Richmond. [10] On April 4, 1861 the convention had voted down a proposed secession amendment by a number of 89 to 45. Lincoln, knowing that the fall of Fort Sumter required an immediate military response, took special care to attempt to reassure Virginians that he would take whatever necessary steps to limit collateral damage. Two days after the proclamation, the Secession Convention passed the Ordinance of Seccession.

The Virginia Ordinance of Secession. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia

The president also tempered his language in this paragraph as can be seen from the original draft of the proclamation. The militia is intended “to redress its injurious [in]sults, and injuries wrongs, already too long endured.” The elimination of the harsher language is important in conveying that Lincoln still hoped for reconciliation at the outset of the War. Conciliatory language was not common after the bombardment of Fort Sumter as the April 18th Chicago Tribune editorial showed, “they are now going to meet the despised and insulted Northerners where blood will flow, and blood will tell.” [11] The president was doubtless hoping that the tempered new language would have also given southerners hope that Lincoln understood their grievances and would address them if the conflict was ended quickly.

The April 15, 1861 Proclamation also laid out clemency for the forces in rebellion. Lincoln ordered the “persons” in revolt to “retire peaceably.” No punishment was lodged or threatened against them for taking up arms against the government. His amnesty for southern combatants indicated what many scholars claim, that Lincoln “had more faith in southern loyalists than events and people would justify.” [12] Lincoln’s call for southerners to return to their homes was unheeded as the southern ranks were bolstered, in response to Lincoln’s call for troops, by the secession of Virginia on April 17th, Arkansas on May 6th, North Carolina on May 20th, and Tennessee on June 8th. [13]

Joseph Medill’s Letter to President Lincoln. Courtesy of the House Divided Project

The president ends the proclamation by calling upon both houses of Congress to meet in a special session on July 4, 1861. He may have chosen the the date in order to feed upon the patriotic fervor taking hold throughout the North. The Chicago Tribune editorial page spoke about the “patriotism which has been kindled in every man’s breast,” in the North. [14] Lincoln used nationalistic wording throughout the proclamation to appeal to this growing sentiment amongst the non-seceding states. In the drafted copy Lincoln edits the proclamation in the following way, “which have been seized from the government; Union,” the replacement of “government” with “Union” illustrated Lincoln’s attempt to harness the current nationalistic attitude of the North that Joseph Medill describes as, “Douglas Dems and Lincoln Reps are a unit, and that is, that Sumter must be retaken.” [15]

Lincoln’s Proclamation of April 15, 1861 accelerated events in what had been a slow run-up to the war. Despite what contemporary and modern critics claim, Lincoln’s call-up of seventy-five thousand troops does not prove he believed the war would be quickly won. On the other hand, the president was mustering the maximum amount of men as prescribed by Congress. The document shows Lincoln’s attempt to harness the North’s patriotism as well his appeal to what he believed to be a mostly loyal South. Throughout the document the president tempered his language in order to appear more conciliatory to the rebels, most likely due to the meeting of the Virginia secessionists. Despite the proclamation’s attempt at assuaging the fears of southerners through a promise to avoid collateral damage and an offer of amnesty, four more states seceded and the bloodshed truly began.

[1] Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times (Philadelphia: Times, 1892), 68-69. [Google Books]

[2] Alexander K. McClure, “Abe” Lincoln’s Yarns and Stories (Chicago: n.p., 1904), 72-73. [Google Books]

[3] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2008), 2420. [file:///Users/lmsrileyblack/Downloads/Burlingame,%20Vol%202,%20Chap%2023%20(1).pdf]

[4] Alexander J. Sessions to Abraham Lincoln, April 16, 1861, Salem, MA, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, March 15, 2015 http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html.

[5] Joseph Medill to Abraham Lincoln, April 15, 1861, Chicago, IL, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, March 15, 2015 http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html.

[6] Brian Holden Reid, The Origins of the American Civil War (London: Longman, 1996), 358. [Google Books]

[7] United States Congress, General index to the laws of the United States of America from March 4th, 1789, to March 3rd, 1827 (Washington D.C.: William A. Davis, 1828), 324. [Google Books]

[8] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2008), 2422. [file:///Users/lmsrileyblack/Downloads/Burlingame,%20Vol%202,%20Chap%2023%20(1).pdf]

[9] Roland Marchand, “The History Project,” University of California Davis, March 18, 2015, http://historyproject.ucdavis.edu/lessons/view_lesson.php?id=13

[10] Nelson D. Lankford, “Virginia Convention of 1861.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. 10 Jan. 2011 <http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Virginia_Convention_of_1861>.

[11] “The Old Fire,” Chicago (IL) Tribune, April 18, 1861, p. 2: 1. [House Divided Project]

[12] William C. Harris, Lincoln’s Rise to the Presidency (Lawerence: University of Kansas Press, 2007). [JSTOR]

[13] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 24.

[14] “Quick, Sharp, and Decisive,” Chicago (IL) Tribune, April 15, 1861, p. 1: 1. [House Divided Project]

[15] Joseph Medill to Abraham Lincoln, April 15, 1861, Chicago, IL, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, March 15, 2015 http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html.

Leave a Reply