Close Reading – Proclamation of Thanksgiving (October 3, 1863)

By: Ellen Tuttle (History 288: Civil War & Reconstruction)

One morning early in October, Seward entered the President’s room

“… I have come to-day to advise you, that there is [another] State right I think we ought to steal.”

Mr. Lincoln looked up from his papers, with a quizzical expression.

“Well, Governor, what do you want to steal now?”

“The right to name Thanksgiving Day!” [1]

When Secretary of State William H. Seward and President Abraham Lincoln discussed the implementation of a national day of Thanksgiving, both men agreed that such an establishment would be more valuable than having individual days organized within each respective state. In the years preceding Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving, a handful of states had been celebrating their own days of thanks, all at different times of year. [2] Based on the account delivered in a compilation of his memoirs, Seward approached Lincoln with his opinion that a day of Thanksgiving be nationally recognized, and Lincoln agreed in saying that, “the usage had its origin in custom, and not in constitutional law; so that a President ‘had as good a right to thank God as a governor.” [1]

Although Lincoln physically communicated the establishment of the national holiday to the public, the organization of the annual celebration was multifaceted, and evolved from the input of other minds such as Seward and author/activist Sarah Josepha Hale. While historians continue to debate the true origins of Thanksgiving, the lobbying effort put forward in its establishment as a national holiday comes solely from Sarah Hale. For most of her career, Hale had written editorials and letters to Governors asking for a widely recognized day of thanks. Additionally, years after the Proclamation had been delivered and published, it was discovered that Secretary of State Seward was the true author of the document. While Lincoln included his own modifications in the transcript, the bulk of the Proclamation came from the pen of the Secretary of State. While Seward’s hand maneuvered the written text of the decree, Lincoln’s verbal delivery was equally vital to the overall success of the effort. In delivering the Thanksgiving Proclamation, and all of his speeches, Lincoln revolutionized the communication between the President and citizens. Despite the complicated nature of the holiday’s development, Hale, Seward, and Lincoln joined efforts to establish a national Thanksgiving which continues to be upheld.

Widow, poet, and writer, Sarah Hale had advocated for a national Thanksgiving for more than twenty years before it was enacted in 1863. Self-educated and the literary editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, Sarah Hale’s editorials evolved from raising questions concerning how the betterment of the domestic American life to focusing on her effort for a nationally recognized day of thanks. [3]

Hale’s first novel, Northwood (1827) set her thanksgiving crusade in motion. Having credited the pilgrims at Plymouth for the origins of Thanksgiving, Hale boldly expressed the moral goodness of having a day set aside for the sole purpose of giving thanks to God. While Northwood presented the idea of Thanksgiving in terms of a New England celebration, Hale’s following novel, Traits of American Life (1835), further pressed her argument for a national day of recognition. As more states, primarily in New England, began to recognize a day of Thanksgiving, Hale brought her opinions into her editorials in Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale emphasized the religious implications of an established Thanksgiving while stressing its potential to unify an increasingly divided nation. [2]

Finally, in 1863, Sarah Hale drafted a letter to President Abraham Lincoln, beseeching him to use his presidential power to enact a national day of Thanksgiving. Hale firmly asserted her position by providing the support of her previous appeals while noting her contact with Secretary of State William H. Seward:

…You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States; it now needs National recognition and authoritative fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution…I have written to my friend, Hon. Wm. H. Seward, and requested him to confer with President Lincoln on this subject… [4]

Hale’s success in communicating with President Lincoln, as well as her victory in the establishment of a national Thanksgiving, demonstrates Lincoln’s devotion to the people whom he governed. While Lincoln could have easily ignored Hale’s letter and request, he not only acknowledged her wishes but granted them as well. The successful correspondence between Hale and Lincoln sheds light upon his innovative approach to President-citizen communication.

Abraham Lincoln was forthright and consistent in his correspondence with the public domain. According to historian Karl Weber, Lincoln’s “risk taking as a communicator” serves as a “useful model for presidents in search of effective strategies”. [5] Lincoln had a talent of communicating with the common man; he often told anecdotes from his own humble life to relate with ordinary people. Additionally, Lincoln was not afraid to admit his shortcomings and failures. In his autobiographical sketch (1859), Lincoln writes about his early life in the back country of Illinois, his simple education, and both his successes and failures in professional life. While he does not attempt to aggrandize his accomplishments, Lincoln’s acknowledgement of his undistinguished history made him more appealing to common citizens. [6]

Another face of Lincoln’s communication effort that struck the public was his tendency to exercise restraint and respect his adversaries. Even when Lincoln discussed the people of the Confederacy, he regarded them as “brothers of whom he asked only that they lay down their weapons.” [5] He avoided from using hostile language or making direct accusations. When faced with opposing opinions, Lincoln simply sought compromise and encouraged the adoption of an open-mindedness approach.

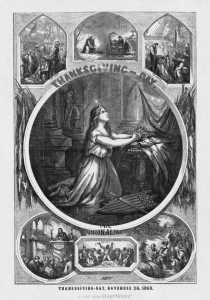

In enacting a national Thanksgiving, Lincoln spoke directly to the people and circumvented state governments. He implored the nation to look beyond the suffering of the war and instead acknowledge the blessings that the nation experienced: retention of order and laws, expanding settlements, and abundance of natural resources. However, the decree made on October 3, 1863 was not the first Thanksgiving proclamation to have been made by Lincoln. By his death in 1865, Lincoln would issue a total of five thanksgiving proclamations and two decrees of national fast days [7]. Such proclamations were often issued after victorious events in the war. For instance, the first thanksgiving proclamation was issued on July 15, 1863 in response to the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, declaring that August 6 of that year be set aside as a day of observance in gratitude for the good fortune that had graced the Union. [8] The proclamation delivered in October of 1863 only specified the celebration of Thanksgiving on the last Thursday in November of that year; Lincoln would deliver another proclamation in 1864 to permanently designate the last Thursday in November as a national day of thanksgiving.

Despite the fact that Lincoln delivered the announcement to the public, most credit concerning the composition of the document is given to Secretary of State William Seward. Acting as Lincoln’s faithful sounding board, Seward, like Lincoln, was a micromanager. Despite their similarities in their approach to organization, Lincoln was often subdued and reserved in his display of opinion, Seward was direct and bold. The contrasting personalities of the two men, in conjunction with their similar beliefs, created a balance that would remain successful throughout Lincoln’s presidency.

According to historian James McPherson, Seward often felt the need to exercise control over most presidential decisions because “[he] had not fully accepted his eclipse as Republican Party Leader.” [9] Having been defeated by Lincoln in the nomination for the Republican presidential candidate in 1860, historians such as McPherson surmise that Seward retained a sense of bitterness after having been conquered by an unknown Illinois lawyer. Seward had been politically distinguished for some years before Lincoln came into the picture. Before Lincoln became known to the general public, he gained popularity by speaking alongside Seward (who was often the keynote orator). However must resentment had existed for Seward after having been beaten Lincoln, he faithfully served the President throughout his time in office.

When the topic of enacting a national Thanksgiving arose, Seward communicated his opinions that one national holiday of Thanksgiving should exist for all states as opposed to “…letting the Governors of States name half a dozen different days…”. [1] While many historians believe that Seward wrote the bulk of Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation, others, such as Roy Prentice Basler, believe that such suppositions are entirely false. In his narrative, Basler delves into the proclamation, and points out errors, such as usage of language and writing characteristics, that falsify the argument that Seward wrote the document. [10] Other historians, such as Walter Stahr in his history of Seward, fully support the notion that Seward drafted the proclamation altogether. [11] Indeed, Lincoln had made his own alterations to the speech, however, it was Seward who developed the address.

In writing the proclamation, Seward made multiple references to God and religion. While frequent references to Christianity may have worked to facilitate Lincoln’s communication with the public, Lincoln himself had his own personal battles concerning religion.

…they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God…set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens…[1]

While historians continue to debate the nature of Lincoln’s belief in God, it is clear that he was not dogmatic in his faith. By the end of his life, Lincoln’s spiritual connection with religion had transformed considerably. While accounts from Mary Todd and William Herndon claim that, at times, Lincoln was openly anti-God, his prose often alluded to belief in a higher power, as seen in documents such as the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Based on the opinion of Stephen Mansfield in his Lincoln’s Battle with God, Abraham Lincoln did have periods in his life in which he was anti-religious. [12]

Lincoln was raised a Baptist, however throughout his adult life, he never joined a church. Furthermore, historians dispute over his religion during his early life. Gastón Espinosa, in his Religion and the American Presidency, argues that Lincoln was devoutly religious as a child, “reading the family Bible over and over”, [7] whereas Mansfield and historian James Matheny claim that Lincoln was heretic in his behavior, publicly denouncing the Bible and its teachings.

Lincoln and Tad Examine the Bible: Image Courtesy of Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom at the Lincoln Institute.

The question becomes whether or not Lincoln’s faith simply evolved throughout his life or if his allusions were all empty. Because of the intense challenges placed upon Lincoln, beginning at an early age with the death of his mother, it is possible that he truly believed in God, however simply chose to privatize the bulk of his spiritual beliefs. Having endured deaths of those he loved, abuse from his father [12], a war within a divided nation, and challenges in his marriage, Abraham Lincoln may have found God in a time where much else was failing him. The topic, however, continues to be debated with many questions still left unanswered.

It is without a doubt that allusion to religion was intended in the Thanksgiving Proclamation. By touching upon Christianity, Lincoln and Seward targeted the innermost beliefs of the public and reminded them of the faith that they could not lose sight of. In alluding to God, Lincoln effectively communicated to citizens by referencing a topic that they could easily relate to; relate to Lincoln and to one another. By having the opportunity to find common ground with one another and the president, citizens could fulfill Sarah Hale’s hope that Thanksgiving would spark unity, and eventually heal the deep wounds of the nation. In working together to permanently establish the beloved national holiday, Hale, Seward, and Lincoln could not have foreseen the unifying effect that their efforts would have on the nation over one hundred fifty years later.

Works Cited:

[1] Frederick W. Seward and William H. Seward, William H. Seward 1861-1872 (Derby and Miller, 1891), 193-194.

[2] “The Godmother of Thanksgiving: The Story of Sarah Josepha Hale,” Pilgrim Society & Pilgrim Hall Museum, accessed March 18, 2015, http://www.pilgrimhallmuseum.org/pdf/ Godmother_of_Thanksgiving.pdf.

[3] “Sarah J. Hale,” National Women’s History Museum, accessed March 15, 2015,

https://www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/sarah-hale/.

[4] “Sarah J. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, September 28, 1863,” Lincoln Studies CEnter at Knox College, accessed March 17, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/ primarysourcesets/thanksgiving/pdf/sarah_hale.pdf.

[5] Karl Weber, Lincoln: A President for the Ages (PublicAffairs, 2012), 193-195.

[6] “Autobiographical Sketch (December 20, 1859),” Lincoln’s Writings: The Multimedia Edition, accessed April 07, 2015, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/ autobiographical-sketch-december-20-1859/.

[7] Gastón Espinosa, Religion and the American Presidency: George Washington to George W. Bush with Commentary Sources (Columbia University Press, 2009), 172-173.

[8] Gerald J. Prokopowicz, Did Lincoln Own Slaves?: And Other Frequently Asked Questions About Abraham Lincoln (Vintage Books, 2009),116-118.

[9] James McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1991), 118-119.

[10] Roy Prentice Basler and Abraham Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and His Writings (Da Capo Press, 2001), 729.

[11] Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (Simon and Schuster, 2013), 380-381.

[12] Stephen Mansfield, Lincoln’s Battle With God: A President’s Struggle With Faith and What it Meant for America (Thomas Nelson Inc., 2012), xvi-xxi, 1-7.

Additional sources:

A.E. Elmore, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Echoes of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer (SIU Press, 2009), 1-3.

Donald Thomas Phillips, Lincoln on Leadership (Donald T Phillips, 1992), 155-156.

Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech that Nobody Knows (Simon and Schuster, 2008), 165-168.

“Proclamation of Thanksgiving (October 3, 1863),” Lincoln’s Writings: The Multimedia Edition, accessed March 05, 2015, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/ proclamation-of-thanksgiving-october-3-1863/.

Leave a Reply