By Ryan Schutte

On November 10th, 1862, twenty-nine year old Margarethe Schurz stood in front of President Lincoln himself and pronounced, “The defeat of the Administration is the Administration’s own fault.” She then accused the President of putting the Union Army, “into the hands of its enemies” and suggested that “There is but one way in which you [Lincoln] can sustain your Administration”[1]. However, these words did not come from Margarethe. She was just the messenger. Mrs. Schurz was sent by her husband, General Carl Schurz, to read a letter containing accusations and recommendations following the 1862 midterm elections.

Margarethe Schurz- Courtesy of With Malice Toward None (Library of Congress)

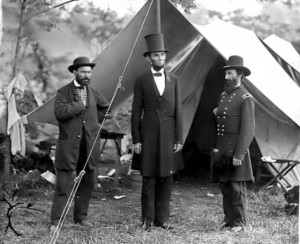

Courtesy of Wikipedia

After receiving a letter of this nature, especially during the political climate at the time, one would expect Lincoln’s response to be an angry one. At first glance, the return letter may even seem that way. However, Lincoln’s letter simply displays a disagreement between two republican leaders. Carl Schurz was a valued asset to Lincoln as an important political and military leader. At a time when voter support was dwindling, support from his allies became even more crucial. Lincoln’s letter of the 10th proved the importance he put on maintaing political relationships in order to achieve his end goal: to crush the rebellion and preserve the Union, free of slavery.

http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/40449

Carl Schurz was born in Liblar, Germany on March 2nd, 1829. College educated at the University of Bonn, Schurz “was strongly influenced by Professor Gottfried Kinkel, a convinced German nationalist…” [2]. In his early years of adulthood, the German Revolution of 1848 was in its beginnings, and the young Carl Schurz joined his mentor in fighting for “radical democratic and republican reforms” [3]. Schurz was forced to relocate to France where he met and married Margarethe Meyer. In 1852, the newly weds immigrated to the United States. Margarethe was educated and trained under Friedrich Froebel to be a kindergarten teacher. She brought these teachings to America, becoming a pioneer for the kindergarten movement with her methods “to enhance children’s learning and social development”[4]. Carl Schurz, on the other hand, immediately found his way into politics, naturally fitting into the Republican Party. Love from the German-American population, along with his anti-slavery sentiments and reputation as an excellent speaker made Schurz a prime Republican candidate. Carl Schurz ignited his relationship with Abraham Lincoln during the Republican National Convention, where he served as a delegate from Wisconsin. There in support of Lincoln, Schurz “…wooed the Germans, and Lincoln was convinced that this effort made a decisive contribution to the Republican victory. Schurz’s reward was an appointment as minister to Spain” [5]. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Schurz convinced Lincoln to give him commission in the Union Army by letter on April 11, 1861 [6]. In May of that year, Lincoln wrote to Schurz saying, “Get the German Brigade in shape, and, at their request, you shall be Brigadier General…”[7]. Despite some military success, he was often criticized and blamed for his performance in key battles, including Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and Wauhatchie, in the Chattanooga Theatre, for his military failures [8].

Lincoln’s name proposed at convention- Courtesy of With Malice Toward None (Library of Congress)

The exchange between Lincoln and Schurz on November 10th was not the first, and was certainly not the last. One could ask why Lincoln, as President of the United States and Commander in Chief, would tolerate this kind of feedback from Schurz, a subordinate? Throughout the war, Lincoln actually appointed several generals with political goals in mind. Many times these men, Schurz included, were politicians first, with little to no military experience. Brooks Simpson explains, “…by making such men generals, the president satisfied political constituencies whose support was critical to a successful prosecution of the Union war effort” [9]. Their support was so important to Lincoln that he actually attempted to protect them in a way. Brooks Simpson described a scenario involving one of Lincoln’s political generals, Nathaniel P. Banks, and Grant’s demand for his removal from command. Even though Lincoln was aware of Banks’ incompetence, he was reluctant to make a change. It took almost a month, and a formal request from Grant until Lincoln removed Banks from command. Simpson commented, “Partisan considerations clearly outweighed military ones in this dispute” [10]. Several debates ended in this same manner where “partisan considerations” overrode military action. According to Michael Burlingame, “Lincoln regarded [Schurz] as a kind of surrogate son” [11]. Lincoln’s sense of value in their political relationship influenced his pragmatic willingness to deal with Carl Schurz’s insubordination.

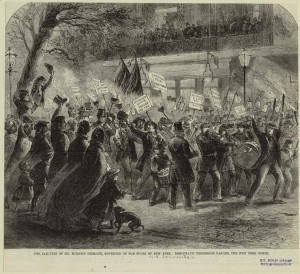

When the the war first began, Northern morale was high and it was believed it would quickly come to an end. Over a year into the conflict, however, all hopes for a quick end were gone. Engagements such as the first and second battles of Bull Run, Shiloh Church, “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Campaign, and McClellan’s failed Peninsula Campaign solidified this sentiment. Louis P. Masur explained, “…Americans were beginning to realize just how bloody a price would be paid, not for glory but for peace” [12]. This war-weary sentiment gave Democrats an opportunity to win over votes. Peace Democrats, also known as Copperheads, “…promised a quick peace and the restoration of the Union ‘as it was'”[13]. Voters were quickly persuaded by this thought of peace. As a result, Republican outlook for the midterm elections in 1862 was poor, and if not for the Union victory at Antietam, would have been worse. Even with this key victory, the elections hit hard in opposition to the Republican party where Democrats had a net gain of twenty-eight seats in the House. As if that wasn’t demoralizing enough for Republicans, Democrats also succeeded in the state elections where they won the state houses in New Jersey, Illinois, and Indiana, as well as the governorships of New York and New Jersey [14]. Following the midterm elections, the Boston Daily Advisor proclaimed, “The overwhelming republican majorities of two years ago have melted away…It is impossible to disguise the fact that a feeling of dissatisfaction has been spreading among the people, at the slow progress and meagre results of the war…” [15]. These results were the fuel for Carl Schurz’s letter of November 8th, where he expressed his concerns to Lincoln pronouncing, “…the results of the elections was a most serious and severe reproof to the administration…” [16].

Lincoln began his response with an embrace of defeat declaring, “We have lost the elections…” There was no disputing this fact, however, the president then gave his own reasons for the midterm defeats. He began by claiming,“The Democrats were left in a majority by our friends going to the war… and determined to reinstate themselves in power…” Even though the Southern states had seceded, many of the Democrats they elected to Congress still remained. Lincoln’s third and final point refers to the newspapers “vilifying and disparaging the administration,” which persuaded public opinion and gave the Democrats the “weapons” to win back power. Newspapers allowed readers around the United States to keep up to date with wartime news. Many Republican affiliated newspapers existed such as the New York Times, who threw support for Lincoln and his administration. On the other hand, Democratic affiliated newspapers attempted to “vilify” it. Papers such as the New York World, The Chicago Times and the Richmond Dispatch provided plenty of fuel for the Democratic Party against the Lincoln administration. In 1863, General Ambrose went as far as to order the suppression of The Chicago Times. Although President Lincoln lifted the general’s ban, he later sent another order “telling Burnside he might let the suppression stand temporarily,” proving his dissatisfaction of the paper [17]. In 1864, under a similar political situation, Copperhead newspapers were still arguing “If nothing else would impress upon the people the absolute necessity of stopping the war, its utter failure to accomplish any results…would be sufficient”[18].

Even pro-Union Newspapers such as the New York Times could not hide the death and destruction resulting from the war. Photographers such as Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and James Gibson helped make battle scenes available to the public, especially in photographs from Antietam. However, many of these photos depicted mostly Confederate dead, as these photographers were Republican-affiliated and supported the war effort. Regardless, civilians were now able to see real-life pictures of the cruelty of war. Brady in particular made an impact to the public with his gallery in New York City titled, “The Dead of Antietam.” A New York Times reporter visited and reviewed the gallery. On October 10th, the review was posted. It read:

“The dead of the battle-field come to us very rarely, even in dreams. We see the list in the morning paper at breakfast, but dismiss its recollection with the coffee….Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought the bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it….We should scarce choose to be in the gallery, when one of those women bending over them should recognize a husband, a son, or a brother in the still, lifeless lines of bodies, that lie ready for the gaping trenches….Homes have been made desolate, and the light of life in thousands of hearts has been quenched forever. All of this desolation, imagination must paint[,] for broken hearts cannot be photographed” [19].

Although few actually visited the gallery, the incredibly descriptive and vivid review in the New York Times forced all readers to imagine a heart-broken widow, mother, or sister devastated over their loss. Newspaper articles like these allowed readers to recognize the destruction the war created, and helped strengthen war-weary sentiments and the desire for peace.

Lincoln finished his “three main causes” suggesting “…the ill-success of the war had much to do with this [defeat].” Lincoln aimed to show that the failures of the midterm election could not be put solely on the administration. He reaffirmed this belief in a follow up letter to Schurz saying “…we lost the late elections, and the administration is failing, because the war is unsuccessful; and that I must not flatter myself that I am not justly to blame for it” [20]. In the opening paragraph, Lincoln admitted defeat in the elections, but also casted blame away from his administration. His “three main causes” exemplify his attempt to shift blame away in order protect his administration’s objectives and maintain support.

In the second paragraph of the letter, Lincoln gives a list of Schurz’s accusations that he would later refute.

“You give a different set of reasons. If you had not made the following statements, I should not have suspected them to be true. “The defeat of the administration is the administrations own fault.” (opinion) “It admitted its professed opponents to its counsels” (Asserted as a fact) “It placed the Army, now a great power in this Republic, into the hands of its’ enemys” (Asserted as a fact) “In all personal questions, to be hostile to the party of the Government, seemed, to be a title to consideration.” (Asserted as a fact)…”

After each of Schurz’s quotes, Lincoln put in parentheses “opinion” or “asserted as a fact.” These remarks convey Lincoln’s slight irritation upon hearing Schurz’s arguments. After all, this was not the first time he had heard similar claims. For example, congressman David D. Field sent a letter to Lincoln on the same day as Schurz containing his “Four Complaints” of the administration. In his opening, Field said, “The elections are very significant; nobody who observes carefully can fail to understand them. The people are dissatisfied” [21]. Still, it is important to notice that Lincoln was not overly hostile in his response to Schurz. The usage of parentheses allowed him to reveal Schurz’s lack of information in a more mild manner.

In the third and final paragraph of the letter, Lincoln gives a counter to each of Schurz’s arguments. He started by refuting Shurz’s first asserted fact, accusing the administration of giving Democrats too many positions of power. He stated, “The administration came into power, very largely in a minority of the popular vote.” Here, Lincoln argued that while he won the election in 1860, with 180 electoral votes, he won only 40% of the popular vote [22]. He continued, “Notwithstanding this, it distributed to it’s party friends as nearly all the civil patronage as any administration ever did.” Many of the distributions to “party friends” came in the way of military appointments. Brooks D. Simpson labeled some of these appointees as “…men who owed their stars to their prewar political prominence…” In his essay, Simpson names Benjamin Butler, Nathaniel Banks, John McClernand, and John Frémont as some men who fit this description. Carl Schurz could be added to this list as well. He comments on Frémont saying he “…possessed some military experience, but his status as the first presidential nominee of the Republican party proved far more important in the decision to make him a general” [23].

The President went on to argue that “It was mere nonsense to suppose a minority could put down a majority in rebellion.” He pointed out that the war was against the South, consisting almost entirely of Democrats. It would make no sense to put down a rebellion of Southern Democrats without using the Democrats who still identified with the Union.

Lincoln then broke down Schurz’s second “asserted fact” that he had “…placed the Army…into the hands of its’ enemies.” He addressed Schurz as “Mr Schurz (now Gen. Schurz).” With this, Lincoln gave a reminder that he was at least one Republican in a high military office. Lincoln continued by disproving the accusation that “…all who were not republicans, were enemies of the government, and that none of them must be appointed to to [sic] military positions.” He noted that very few Republican leaders “…had a military education or were of the profession of arms.” On the other hand, there was an abundance of qualified Democrats. He backed up his decisions by referring to Republican support from the Governors of Ohio and Pennsylvania. Lincoln added he “…received recommendations from the republican delegations in congress….” Also, throughout Lincoln’s refutation of the second “asserted fact” he began to refer to Schurz in the third person. Examples include:

“…I do not recollect that he then considered…”, “He will correct me if I am mistaken.”, and “…our own friends (I think Mr. Schurz included) seemed to think…”

In the second paragraph of his letter, Lincoln’s counters were an attempt to remind Schurz of the facts and to remain rational in the face of the recent election defeats.

Lastly, Lincoln argued against Shurz’s third and final asserted fact that the administration had been hostile to its own party. He claimed, “But, after all many Republicans were appointed…” in reference to the previously mentioned Banks, Frémont, McClernand, Butler, and, of course, Schurz himself. He then commented on Schurz and other Republican appointees saying, “…I do not see that their superiority of success has been so marked as to throw great suspicion on the good faith of those who are not Republicans.” In other words, Lincoln was saying that Republicans in military positions had not had any more success than Democrats in the same positions.

In Carl Schurz’s autobiography, he recalled the chain of letters and encounters he had with Lincoln in November of 1862. The President’s quick response with an “…undertone of impatience, of irritation, unusual with him…” caught Schurz off guard. By Lincoln’s request, the two set up a meeting to talk. Schurz explained the encounter saying, “Then he [Lincoln] described how the criticisms coming down upon him from all sides chafed him, and how my letter…had touched him as a terse summing up of all the principal criticisms and offered him a good chance at me for a reply” [24]. This reveals that while Lincoln’s response was slightly stern, it was a result of constant criticism he was receiving from countless republican leaders. Schurz recalled the end of their meeting saying, “I asked whether he still wished that I should write to him. ‘Why, certainly,’ he answered; ‘write me whenever the spirit moves you.’ We parted as better friends than ever” [25].

At first glance, the letter from President Lincoln to General Schurz may give the impression of a cold relationship. After all, most of Lincoln’s letter was dedicated to the refutation of Schurz’s initial letter of the 8th. But thats just it. Lincoln and Schurz were simply in an argument at a time of a significant political hit. What’s important to notice about this letter is the lack of hostility and the calm demeanor from Lincoln’s side. From an outside view, Carl Schurz was a subordinate to Lincoln, clearly overstepping his boundaries. In reality, however, the value of Schurz as a political ally overrode this fact. Lincoln was willing to accept insubordination in return for political harmony at a time when support was hard to find. Without backing from the nation’s leaders, there would be no backing for the war itself. Schurz exemplified a strong republican leader, with constituents and common goals, whose support was crucial for the war effort. Lincoln believed strong political support would be a major stepping stone toward his end goal: to crush the rebellion and preserve the Union, free of slavery.

[1] “Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, Saturday November 08, 1862 (Political and military advice).” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/194/1944700/001.jpg

[2]Trefousse, Hans L. “Schurz, Carl.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

[3]Trefousse, Hans L. “Schurz, Carl.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

[4]Beatty, Barbara. “Schurz, Margarethe Meyer.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

[5]Trefousse, Hans L. “Schurz, Carl.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

[6] “Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, Thursday, April 11, 1861 (Military commission).” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/089/0898200/001.jpg

[7] “Abraham Lincoln to Carl Schurz, [May 13, 1861] (Appointment as Brigadier General).” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/098/0985200/001.jpg

[8]Trefousse, Hans L. “Schurz, Carl.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

[9]Simpson, Brooks D. “Lincoln and His Political Generals.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 2000. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0021.105.

[10]Simpson, Brooks D. “Lincoln and His Political Generals.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 2000. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0021.105.

[11] Burlingame, Michael. “I Am Not a Bold Man, But I Have the Knack of Sticking to My Promises!” In Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 3176. Vol. 2. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

[12]Masur, Louis. “1862.” The Civil War a Concise History, 118. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011. 34.

[13]Von Drehle, David. “Wartime Elections: Lincoln, November 1862.” Command Posts. October 31, 2012. http://www.commandposts.com/2012/10/wartime-elections-lincoln-november-1862/.

[14]Masur, Louis. “1862.” The Civil War a Concise History, 118. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011. 44.

[15]”It is now certain that the fall elections have resulted for the administration in the loss of the next House of Representatives.” Boston Daily Advertiser [Boston, Massachusetts] 7 Nov. 1862: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

[16]Von Drehle, David. “Wartime Elections: Lincoln, November 1862.” Command Posts. October 31, 2012. http://www.commandposts.com/2012/10/wartime-elections-lincoln-november-1862/.

[17] Tenney, Craig D. “To Suppress or Not to Suppress: Abraham Lincoln and the Chicago Times.” America: History and Life Online. 46. September 1981.

[18]McPherson, James M. “No Peace without Victory, 1861-1865.” He American Historical Review 109, no. 1, 18. http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2012/01/McPherson-article.pdf.

[19]Masur, Louis. “1862.” The Civil War a Concise History, 118. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011. 44.

[20]”Abraham Lincoln to Carl Schurz, Monday, November 24, 1862.” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/197/1973100/001.jpg

[21] David D. Field to Abraham Lincoln, Saturday, November 08, 1862 (Election results). The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/194/1942600/001.jpg

[22] Pinsker, Matthew. “The 1860 Election and the Coming of Civil War.” History 288: Civil War and Reconstruction. http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/ .

[23]Simpson, Brooks D. “Lincoln and His Political Generals.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 2000. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0021.105.

[24]”The Officers: Carl Schurz (1829-1906).” Abraham Lincoln and Friends. http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/inside.asp?pageID=92&subjectID=8.

[25]”The Officers: Carl Schurz (1829-1906).” Abraham Lincoln and Friends. http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/inside.asp?pageID=92&subjectID=8.

Sources

“Abraham Lincoln to Carl Schurz, [May 13, 1861] (Appointment as Brigadier General).” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/098/0985200/001.jpg

“Abraham Lincoln to Carl Schurz, Monday, November 24, 1862.” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/197/1973100/001.jpg

Beatty, Barbara. “Schurz, Margarethe Meyer.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

Burlingame, Michael. “I Am Not a Bold Man, But I Have the Knack of Sticking to My Promises!” In Abraham Lincoln: A Life, 3176. Vol. 2. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

“Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, Thursday, April 11, 1861 (Military commission).” The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/089/0898200/001.jpg

David D. Field to Abraham Lincoln, Saturday, November 08, 1862 (Election results). The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mal/mal1/194/1942600/001.jpg

“It is now certain that the fall elections have resulted for the administration in the loss of the next House of Representatives.” Boston Daily Advertiser [Boston, Massachusetts] 7 Nov. 1862: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

Masur, Louis. “1862.” The Civil War a Concise History, 118. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011.

McPherson, James M. “No Peace without Victory, 1861-1865.” He American Historical Review 109, no. 1, 18. http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/files/2012/01/McPherson-article.pdf.

Pinsker, Matthew. “The 1860 Election and the Coming of Civil War.” History 288: Civil War and Reconstruction. http://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/ .

Simpson, Brooks D. “Lincoln and His Political Generals.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. January 1, 2000. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0021.105.

Tenney, Craig D. “To Suppress or Not to Suppress: Abraham Lincoln and the Chicago Times.” America: History and Life Online. 46. September 1981.

“The Officers: Carl Schurz (1829-1906).” Abraham Lincoln and Friends. http://www.mrlincolnandfriends.org/inside.asp?pageID=92&subjectID=8.

Trefousse, Hans L. “Schurz, Carl.” American National Biography Online. February 1, 2000.

Von Drehle, David. “Wartime Elections: Lincoln, November 1862.” Command Posts. October 31, 2012. http://www.commandposts.com/2012/10/wartime-elections-lincoln-november-1862/.