Expanding off a previous research journal post, I continued searching the Dickinson College archives for references to slave labor in the construction of the first two college buildings. The Board of Trustees Papers (RG 1/1) are where Georgetown University’s Cory Young first discovered a mention of “Black James, Mr. Holmes’ Negro” who was paid 15 shillings for work on the college on July 26, 1799.

I first wanted to follow up on John Holmes, who as a slave owner was more likely to generate records than the bondsman James. To do so, I used the record group’s finding aid, available online. There, each series within the group is broken down into boxes and then folders, with brief descriptions of their contents. Looking through the finding aid for Series 6, (the Financial Affairs records) I found a folder labeled “Bill of John Holmes for expenses incurred while collecting subscriptions in Baltimore.” True to the description, the folder contained a bill submitted on April 16, 1799, listing Holmes’ expenses on a trip collecting subscriptions to fund the new college’s construction. The first slip showed Holmes’ request to be reimbursed for “2 Horses” and “36 Gallons of Oats,” but on the second slip the otherwise mundane document assumed a new light. Tallying the expenses, Holmes also sought reimbursement “for Jem and two horses for Sixteen Days,” almost certainly the same “Black James” who would appear again, just three months later, in the financial ledger already discovered by Cory Young. [1]

John Holmes’ bill for expenses, April 16, 1799. (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections)

Holmes asks to be reimbursed for “Jem and two horses for Sixteen Days” (Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections)

This record suggests that James, the slave of John Holmes, accompanied his master to Baltimore, and that Holmes billed the college for James’s time. It is an indication that enslaved people were hired out to Dickinson College not just within the limits of Carlisle, but also in the course of larger fundraising efforts. [2]

These records, from 1799, pertain to New College, the initial college building constructed between 1798-1803. As it neared completion, however, the structure burned in early 1803, and a new fundraising campaign was launched to build what is today know as West College, or Old West. I sought to broaden the scope of my research by looking into contracts arranged for the building of West College, and see if any enslaved labor was used in its construction.

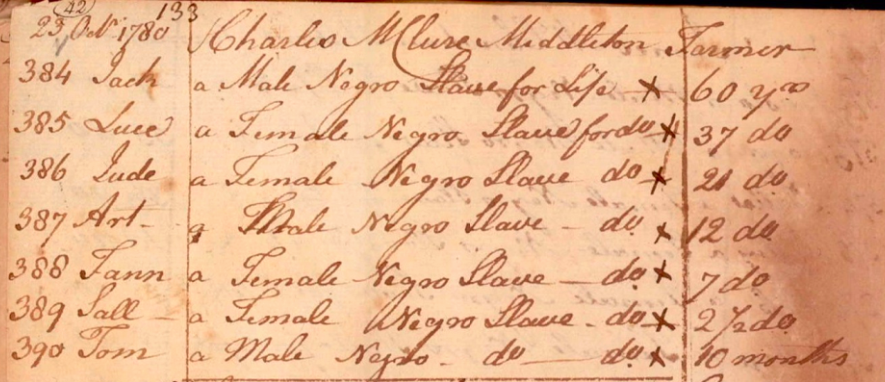

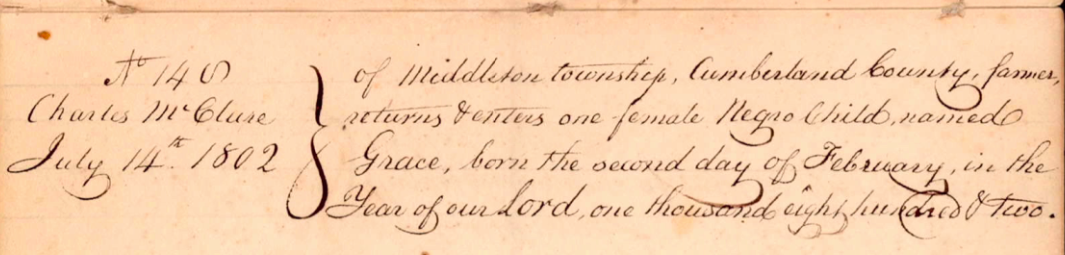

Using the same finding aid, I noticed a file named “Contracts for goods and services, including a partial list of contractors.” Inside was a handwritten list of contractors whom the college had hired, as well as the material they were to supply. I referenced the names against those of slave owners appearing in the Cumberland County Slave Returns to see which of the suppliers owned slaves. While at least three of the contractors had registered slaves in 1780, it proved more difficult to verify whether or not they still owned slaves some 23 years later. There was one exception: Charles McClure, a farmer from neighboring Middleton township, who had served as a Trustee of the college since 1794. McClure, who had agreed to deliver 3,000 bushels of sand for the building of West College, had previously registered seven slaves in 1780, and more recently the birth of a “Negro Child named Grace” in 1802. [3]

Charles McClure registers 7 slaves in October 1780. (Cumberland County Archives)

Charles McClure registers another slave birth in 1802, shortly before he was contracted to work on Old West. (Cumberland County Archives)

While McClure’s slave registrations are far from definitive proof that enslaved labor was used to deliver materials for the building of West College, it does show that the college hired a local slaveholder to supply materials. What remains to be seen is if any more definitive connections between the construction of Old West and slave labor can be made.

Notes

[1] Bill of John Holmes, April 16, 1799, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 6.4.33, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections.

[2] As noted in my previous post, a man named William Holmes registered a “Negroe boy named Jim” in October 1780. Georgetown University’s Cory Young has found that William Holmes died within several years of registering “Jim,” sometime prior to August 1785. (See Estate Advertisement, Carlisle Gazette, August 17, 1785, Readex Early American Newspapers Database). It is possible that “Jim” went from William Holmes to his brother, John Holmes. Regardless, what remains clear is that by 1799, John Holmes owned an enslaved man of working age known alternatively as “James” or “Jem.”

[3] Contracts for Goods and Services, West College 1803, RG 1/1 Board of Trustees Papers, Series 5.4.4, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; Carla Christiansen, “Samuel Postlethwaite: Trader, Patriot, Gentleman of Early Carlisle,” Cumberland County History, 31 (2014): 34.