William Parker was born a slave, lived an abolitionist, and died a free man. He became well-known after his leadership role in the Christiana Resistance, or Riot, of 1851, an incident in which Parker and his band of runaway slaves and abolitionists beat off slaveholder Edward Gorsuch, a federal marshal, and others seeking to reclaim four of Gorsuch’s slaves.[1] Published in 1866, one year after the Civil War, Parker’s autobiography is similar to many other slave narratives, as it seems to have been written to “enlighten white readers about slavery” and to showcase “the humanity of black people.”[2] The reality of slavery can be demonstrated by his detailing of his deep fear of being sold, and it is nearly impossible to deny the humanity and agency of Parker, who claimed to have earned his “rights as a freeman” with his “own right arm,” an expression meaning that he had to fight for his freedom.[3]

Born in 1822 at Roedown Plantation in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, William Parker was the property of Major William Brogdon.[4] Brogdon died when Parker was very young, so his son, David, received ownership of Parker and moved him to Nearo.[5] Though Parker states that his masters – David and his brother, William – didn’t have their “hands beaten or abused,” he does note that they sold slaves, sometimes “six or seven at a time,” every year.[6]

Parker recounts the story of one sale in particular that stuck out to him. When he was ten or eleven, he recalls seeing “negro-traders” one morning and running away to some nearby woods with Levi Storax, “a boy of about [his] own age,” to avoid being sold. When in the woods, he told Storax that they should “’run away to the Free States’” to ensure that they would never be sold, but Storax reasoned that they would likely be caught. Though they didn’t run that day, Parker’s instinct to flee shows remarkable initiative for a preteen and foreshadows his later decision to escape. To Parker, slave sales in general were as “solemn as a funeral,” but he feared sale to the Deep South above all, reasoning that slave owners there committed even worse “atrocities” than the more “mild” and “humane” masters of the “Northern Slave States.”[7]

Parker’s terms of and reasoning for escape were relatively common. He ran away at roughly seventeen with his brother, Charlie. Many runaway slaves were young men as they often had fewer reasons to stay than parents, with Parker himself noting that he had “no attachments.”[8] Furthermore, runaways were safest “alone or in pairs,” as it was easier for them to avoid suspicion or detection.[9] In regards to his desire to run away, he did not want to be sold, and he generally “longed to cast off the chains of servitude.” However, he felt the need to wait until he and his master had a specific “difficulty” or conflict, which eventually arose when Parker refused to work one day, and Master David attempted to whip him.[10] This general desire and need for an actual incident to occur fits well with Peter Kolchin’s argument that runaways typically felt “a general hatred for slavery” but did not run away until confrontation “triggered the determination to act.”[11]

Parker and his brother stopped in Baltimore, blending in with its high population of free-blacks, before eventually settling in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[12] Parker found work in Lancaster, and while working for and living with a man named Dr. Dengy, he met a “true friend of the slave,” William Lloyd Garrison, and reunited with Frederick Douglass, who he had known as “a slave in Maryland.” He seems to have been greatly affected by Garrison and Douglass, who impressed Parker with his “strong speech” and whose “doctrine” was “so pure, so unworldly.”[13]

Parker’s description of Garrison and his feeling that “Garrisonian Abolitionists” were “the poor slave’s friend” is rather ironic. Garrison was in charge of the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, and for a time was the “major force voice of radical abolitionism.” Notably, he “rejected all use of force,” but William Parker definitely did not, as he resorted to violence to prevent slave catchers from capturing runaway slaves or kidnapping free blacks. As such, Parker’s philosophy of securing freedom by any means necessary is more reflective of David Ruggles, founder of the New York Vigilance Committee, who believed that runaways and their allies should “resist even unto death.”[14] Regardless, it is highly likely that Parker was inspired by Garrison and Douglass to lead a life of abolition

In 1841, Parker and others founded “an organization for mutual protection against slaveholders and kidnappers,” that would resist any attempt to kidnap and enslave their “brethren” at “the risk of [their] own lives.”[15] Parker and his organization were more than willing to use violence to “protect their very tenuous liberty.”[16] In the ten years between the organization’s founding and the Christiana Resistance, Parker details numerous instances of he and his followers protecting blacks, some runaways and others likely not, from recapture or kidnapping. For instance when slave catchers snatched a “colored maid,” Parker’s group followed them to Gap Hill, and they killed three of them during the ensuing confrontation. On another occasion, they tracked kidnappers to a tavern, and when the owner refused to let them inside, Parker beat the door in. Parker’s group exchanged fire with the slave catchers and “people from the neighboring houses.” Parker was hit, but they still rescued the captive man.[17] By the time of the famous Christiana Resistance, William Parker and his cohorts were well versed in fighting slave catchers.

Before 1850, the act of recapturing a runaway slave laid with the runaway’s owner, but the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 “required citizens to assist in the capture of fugitives and overrode local laws” that would hinder “their return,” making rendition a federal issue.[18] The fugitive slave law angered abolitionists, but it made slave owners more confident that their property would be returned. However, the act was rarely enforced, as evidenced by the Christiana Resistance.

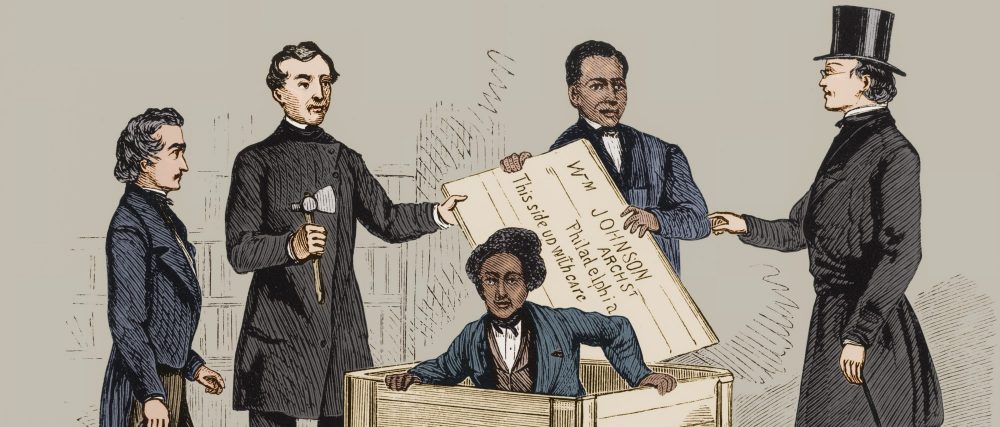

The fateful day of the riot occurred early in the morning of September 11th, 1851 when Joshua Kite, one of four men who had slept at Parker’s home the previous night, came running inside yelling “kidnappers!” Kite and the others must have known that they were coming though because they had been warned by the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia.[19] Kite was explaining what had happened outside when they burst in the door. Parker “met them at the landing,” and when a man told him he was a United States marshal, Parker responded that if he took “another step,” he “would break his neck,” exemplifying his willingness to do whatever it took to protect his friends – some of the men at Parker’s house belonged to the leader of the kidnapping party, Edward Gorsuch.[20]

The two groups engaged in a lengthy standoff with neither one willing to make a move. During this time, Parker’s wife “blew a horn” which notified Parker’s organization and sympathizers that kidnappers had arrived and signaled that they may need help. While trying to convince each other to give up, Parker and Gorsuch “engaged in biblical debate,” with each reasoning that the Bible was on their side.[21] According to Parker’s recollection, the fighting began when Gorsuch’s son asked if he would “take all this from a nigger.” Parker responded that if Gorsuch’s son said that again, he would “knock his teeth down his throat.” Then, Gorsuch’s group “fired upon” Parker.[22]

The fighting would end with Gorsuch dead, and the slaves still free. Parker’s men were victorious in defying a federal law. Over 35 people in total, including Parker, his family, and others “who did not actually participate in the resistance” were charged with treason for violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.[23] Parker safely escaped to Canada, and everyone else was acquitted, meaning “no one was found guilty in the “murder of Edward Gorsuch.”[24]

This result was celebrated by abolitionists and lambasted by slave owners. A white man that Parker met on his journey to Canada called Parker “a brave man” and argued that “any good citizen” would have done what he did. Of course, this man had no idea that he was actually travelling with William Parker himself.[25] Frederick Douglass, who helped “Parker and two others” flee to Canada, called them “heroic.” However, Southerners saw the Christiana Resistance as a riot, and viewed the whole situation as “an attack on property rights,” demonstrating the intense sectionalism of the era.[26]

William Parker would continue his anti-slavery in Canada, becoming the “Canadian correspondent for Douglass’ newspaper, the North Star.”[27] Parker and the Christiana Resistance are largely forgotten today, but Parker shows that some abolitionists would fight to the death before allowing themselves or their friends to be recaptured. The Christiana Resistance was hugely controversial, and it dealt a sizable blow to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. William Parker was a key figure in the abolitionist movement, despite his lack of name recognition.

[1] John Anderson, “Christiana Riot of 1851,” Black Past, last accessed November 5, 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/christiana-riot-1851

[2] William L Andrews, “An Introduction to the Slave Narrative,” Documenting the American South, last accessed November 5, 2017. http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/intro.html

[3] “William Parker, fl. 1851, The Freedman’s Story: In Two Parts,” The Atlantic Monthly, vol. XVII, (Feb 1886), 154.

[4] John Gartell, “Roedown Plantation and the Christiana Resistance,” Legacy of Slavery in Maryland, last accessed November 5, 2017.

[5] Parker, 154.

[6] Parker, 154.

[7] Parker, 154-155.

[8] Parker, 155.

[9] Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003), 161.

[10] Parker, 157-158.

[11] Kolchin. 163.

[12] Kolchin, 84 and Parker, 158.

[13] Parker, 160-161.

[14] Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), 63 and 74-75.

[15] Parker, 161.

[16] Ella Forbes, “’By My Own Right Arm’: Redemptive Violence and the 1851 Christiana, Pennsylvania Resistance,” The Journal of Negro History 83, no. 3 (1998): 164.

[17] Parker,161-164 and Roderick W. Nash, “William Parker and the Christiana Riot,” The Journal of Negro History 46, no. 1 (1961): 4.

[18] Foner, 18 and 25.

[19] Forbes, 164.

[20] Parker, 283

[21] Forbes, 164-166.

[22] Parker, 286-287. For Parker’s full story of the battle and its immediate aftermath, see Parker, 283-288.

[23] Forbes, 164.

[24] Nash, 29-30.

[25] Parker, 289-290.

[26] Nash, 29-31.

[27] Colin McBride, “William Parker,” Black Past, last accessed November 5, 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/william-parker