By Rachel Morgan

Click here to view StorymapJS on Jacobs’s life

In the 1970s, scholars of American slavery started a historiographical revolution by “bringing the slaves themselves to center stage in the drama of history.”[1] In an effort to reject historian Stanley M. Elkins’ “Sambo thesis,” which promoted the idea of “slave docility,” scholars began to research slaves’ personal experiences, rather than just analyzing their treatment at the hands of their white masters.[2] Today, slave narratives continue to be an important part of this academic field. They allow researchers to recognize some level of slave agency, rather than view slaves as forces that were merely acted upon. Harriet Jacobs’ narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, is one such critical work that gives slaves some level of autonomy and helps scholars to understand slaves as individual, distinct people, rather than a homogeneous group.

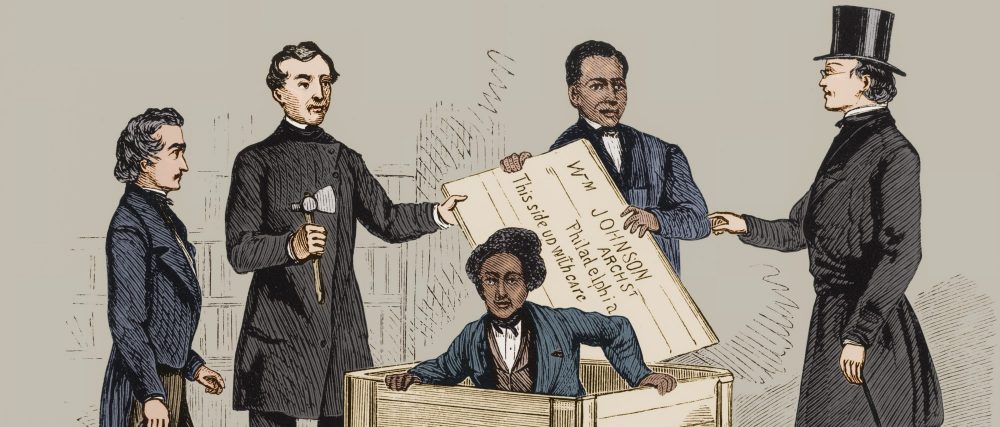

Harriet Jacobs, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

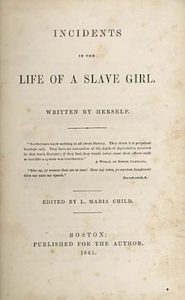

Jacobs first published her narrative in 1860, with the help of Lydia Marie Child as her editor.[3] To protect her own as well as others’ identities, Jacobs gave fake names to both herself and others mentioned in the narrative. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl tells the story of Linda Brent (Jacobs), a young slave born in Edenton, North Carolina. After the death of her mistress, Brent is sent to live in the house of Dr. Flint (Dr. James Norcom), and his family. When Brent turns fifteen, Flint begins to make unwanted sexual advances upon her. In response to his advances, Brent becomes the lover of Mr. Sands (Samuel Tredwell Sawyer), out of the hope that he will eventually free her and any children she may have with him. Brent and Sands do eventually have two children together, Benjamin (Joseph) and Ellen (Louisa). Not wanting Flint to have any control over her children, Brent runs away and spends seven years hiding in her grandmother’s attic, prompting Flint to sell her children to Sands out of frustration. However, instead of freeing the children, Sands sends Ellen to work for his relatives in Brooklyn. This prompts Brent’s escape to the North, which begins in 1842. She eventually reaches Brooklyn, where she reunites with her daughter and eventually sends for her son. She begins working as a nursemaid for the wife of Mr. Bruce (Evening Mirror editor Nathaniel Parker Willis). In 1852, Bruce’s second wife purchases Brent’s freedom from Flint’s son-in-law, finally breaking Brent’s chains of slavery.

For years, historians had grappled with the story of Linda Brent, unsure of how to understand it. This is because, for over a century after the narrative was published, there was not enough evidence to prove that Brent was actually Harriet Jacobs, and that Incidents was autobiographical. For this reason, the narrative was often overlooked or disregarded as fiction. This changed in 1981, when Jean Fagan Yellin discovered and made public various letters Jacobs wrote to Amy Post and Lydia Marie Child, which confirmed that Brent’s story was in fact Jacobs’ story.[4] Post was a Quaker “feminist and abolitionist,” who Jacobs had met in Rochester.[5] Child was the editor of Incidents, and in one letter, Child confirmed that “I have very little occasion to alter the language,” and otherwise made few edits to the narrative.[6] Thanks to Yellin’s research, historians could be certain that Incidents was Jacobs’ way of making her story known. The account was added to the array of narratives being studied in the 1980s, as an extension of the work begun in the 1970s to disprove the “Sambo thesis.”

How do scholars understand Jacobs’ framing of her narrative? What could this narrative teach historians about slave autonomy? Kolchin argued, in 2004, “Some of these arguments [of the 1970s and 1980s] for slave autonomy have been overstated and eventually will be modified on the basis of future evidence.”[7] While Kolchin concedes that slaves like Jacobs exercised some autonomy, they were not completely autonomous. Evidence for this can be seen in Incidents: Brent (Jacobs) chose Sands (Sawyer) as her lover, but only after her master forbade her from marrying a free black man that she actually loved.[8] While she had choices, they were limited by her status as a slave. In choosing to become Sawyer’s lover, Jacobs exerted the little agency that was available to her.

Original Cover of “Incidents of the Life of a Slave Girl,” courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

So how did Jacobs understand her own agency? Did she own her decision to become Sawyer’s lover, or did she try to distance herself from her decision? Incidents was written largely for Northern women, and Jacobs knew that her extramarital affair would possibly offend this audience. Georgia Kreiger argued that Jacobs, during the seven years she hid at her grandmother’s, went through a type of “thanatomimesis,” the process by which animals often “play dead” to protect themselves from predators.[9] Jacobs’ time in hiding was a type of self-imposed death penalty for her actions, “possibly to forestall condemnation of her sexual past by her Northern, white, mostly female readership.”[10] This interpretation focuses on Jacobs’ apologetic tone.

However, despite this tone, Jacobs was upfront about her decision: “I know what I did, and I did it with deliberate calculation…all my prospects had been blighted by slavery.”[11] Jacobs specifically chose Sawyer because she knew she and her prospective children would eventually benefit from the arrangement. In the words of Elizabeth C. Becker, “While a tone of apology admittedly does exist in Jacobs’ recollections, the tone only masks rebellious feelings that Jacobs lets us glimpse through her narrative.[12] Becker argues that, unlike most male slave narratives that would portray slave women as victims, Jacobs portrayed herself as someone who knowingly recognized that, as a slave, she could not be held to the same standards of “true womanhood” as free white women. Consequently, she defied this notion of womanhood by having Sawyer as her lover.[13]

Heidi M. Hanraham, meanwhile, argues that Incidents was written to counteract the “tragic mulatta” trope that was common at the time, a trope which made the slave woman a victim who “is rarely granted voice or agency; she is acted upon rather than acting.”[14] Child, Jacobs’ editor, was guilty of perpetuating this trope in her tale “The Quadroons,” which centers around a young slave woman who suffers and eventually dies after being abandoned by her white lover.[15] According to Hanraham, Incidents is a rejection of this trope. Jacobs made it clear in her narrative that she willingly chose her lover; she did not simply let him do as he pleased with her, as the tragic mulatta normally would. While Kreiger would argue that Jacobs probably felt ashamed of how she exercised what autonomy she had, scholars like Hanraham would argue that Jacobs purposefully acted the way she did so that she would at least be able to say she was in control of her decisions.

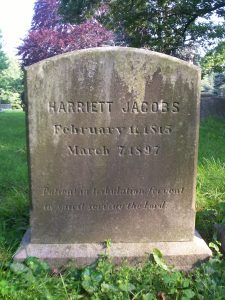

Tombstone of Harriet Jacobs. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is a crucial narrative for scholars to study and understand. It is one of few slave narratives told from a woman’s perspective, and the way in which Jacobs presents the narrative gives enslaved women an agency that had long been denied them. As Becker and Hanraham have argued, Jacobs’ choosing her lover gave her an autonomy that would have been denied enslaved women such as herself in male slave narratives and stories which use the “tragic mulatta” trope. This narrative helps enforce the lesson that, rather as a group of victims who had no say over their lives, enslaved women were individuals who held some degree of autonomy, and even though that autonomy was limited, it was still exercised in ways these women saw fit.

NOTES

[1] Peter Kolchin, American Slavery 1619-1877 (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003), 136. Print.

[2] Kolchin, American Slavery, 135-136.

[3] William L. Andrews, “Harriet A. Jacobs (Harriet Ann), 1813-1897),” Documenting the American South, 2004. [WEB]

[4] Jean Fagan Yellin, “Written by Herself: Harriet Jacobs’ Slave Narrative,” American Literature 53, no. 3 (Nov. 1981), 479. [WEB]

[5] Yellin, “Written by Herself,” 481.

[6] Ibid., 484.

[7] Kolchin, American Slavery, 137-138.

[8] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself (Boston: Published for the Author, 1860), 61. [WEB]

[9] Georgia Kreiger, “Playing Dead: Harriet Jacobs’ Survival Strategy in ‘Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,’” African American Review 42, no. ¾ (Fall-Winter, 2008), 607. [WEB]

[10] Kreiger, “Playing Dead,” 607.

[11] Jacobs, Incidents, 83-84.

[12] Elizabeth C. Becker, “Harriet Jacobs’ Search for Home,” CLA Journal 35, no. 4 (June 1992), 413. [WEB]

[13] Becker, “Harriet Jacobs’ Search for Home,” 415.

[14] Heidi M. Hanraham, “Harriet Jacobs’ ‘Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: A Retelling of Lydia Marie Child’s ‘The Quadroons,’’” The New England Quarterly 78, no. 4 (Dec., 2005), 604. [WEB]

[15] Hanraham, “Harriet Jacobs,” 602.