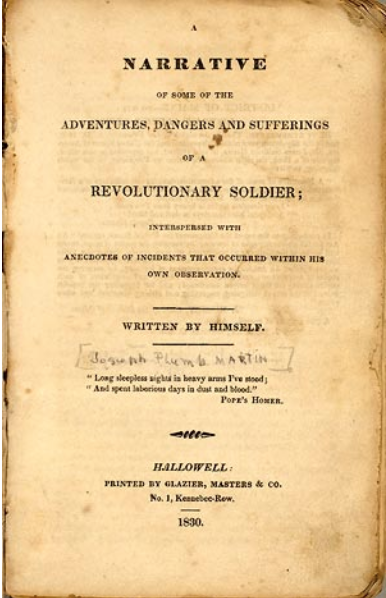

“There are many ways to tell the story [of the American Revolution] —different personnel, different motive forces, different perspectives on the ultimate outcomes—but the essential plot remains the same….But not every story of the Revolution fits so neatly into such providentialist and heroic-nationalist narratives of the Founding. Joseph Plumb Martin’s Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier, first published in Hallowell, Maine, in 1830, offers both a counter-record of the facts of the War and a counter-method for relating them.” —William Huntting Howell

History, Art & Propaganda

“Facts are stubborn things.” –John Adams

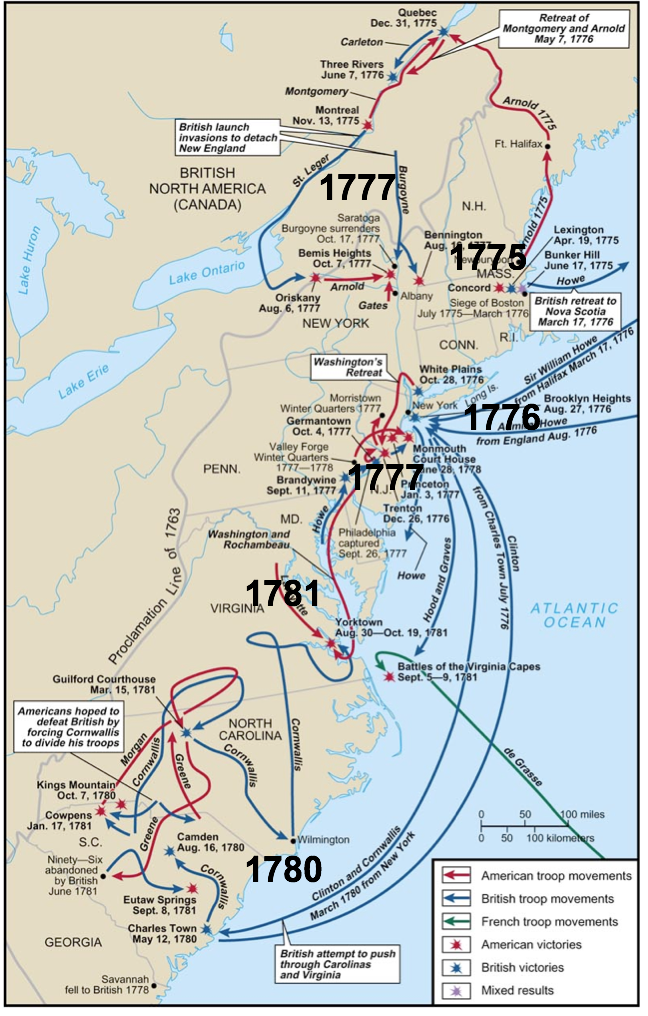

Timeline

- 1770 Boston Massacre

- 1775 Lexington & Concord

- 1776 Declaration of Independence

- 1776 Battle of New York (Pvt. Martin)

- 1777 Battle of Saratoga

- 1777-8 Valley Forge (Pvt. Martin)

- 1778 French Alliance

- 1780 Battle of Charleston

- 1781 Battle of Yorktown (Pvt. Martin)

- 1783 Treaty of Paris

Map

From Joseph Martin’s Narrative (1830)

- Battle of New York (1776)

The soldiers at New-York had an idea that the enemy, when they took possession of the town, would make a general seizure of all property that could be of use to them as military or commissary stores, hence they imagined that it was no injury to supply themselves when they thought they could do so with impunity, which was the case of my having any hand in the transaction I am going to relate…

In retreating we had to cross a level clear spot of ground, forty or fifty rods wide, exposed to the whole of the enemy’s fire; and they gave it to us in prime order; the grape shot and language flew merrily, which served to quicken our motions. When I had gotten a little out of reach of the combustibles, I found myself in company with one who was a neighbour of mine when at home, and one other man belonging to our regiment; where the rest of them were I knew not. We went into a house by the highway, in which were two women and some small children, all crying most bitterly; we asked the women if they had any spirits in the house; they placed a case bottle of rum upon the table, and bid us help ourselves. We each of us drank a glass, and bidding them good bye, betook ourselves to the highway again.

- Philadelphia (1777)

While we lay here there was a Continental thanksgiving ordered by Congress; and as the army had all the cause in the world to be particularly thankful, if not for being well off, at least, that it was no worse, we were ordered to participate in it. We had nothing to eat for two or three days previous, except what the trees of the fields and forests afforded us. But we must now have what Congress said—a sumptuous thanksgiving to close the year of high living, we had now nearly seen brought to a close. Well—to add something extraordinary to our present stock of provisions, our country, ever mindful of the suffering army, opened her sympathizing heart so wide, upon this occasion, as to give us something to make the world stare. And what do you think it was, reader?—Guess.—You cannot guess, be you as much of a Yankee as you will. I will tell you: it gave each and every man half a gill of rice, and a table spoon full of vinegar!!

George Washington on Leadership