On Saturday morning, September 3, 1853, the palaver of travelers hustling to catch the early stage out of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania was abruptly broken, as sounds of a violent confrontation emanated from the dining room of Gilchrist’s Phoenix Hotel. From his room on the inn’s third floor, 51-year-old attorney Henry Pettibone craned his neck out the window, just in time to observe a man he recognized as William Thomas–an African-American waiter employed at the hotel, roughly 30 years in age–throw open the dining room door and head down an alley towards the Susquehanna River, “with two men holding onto him, one at each arm.” [1] Thomas eventually freed himself from the grasp of his would-be captors, but moments later, gun shots rang out, startling residents throughout the small central Pennsylvania borough.

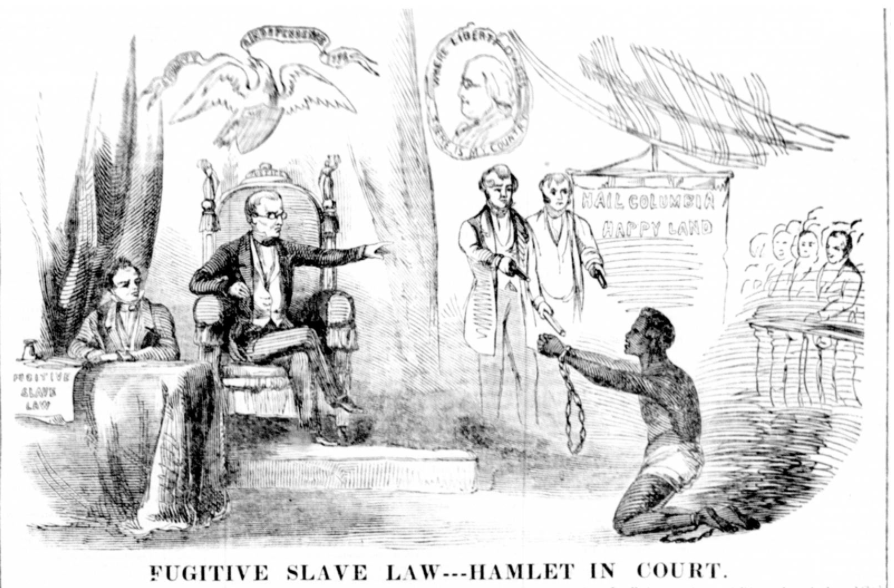

As locals would soon learn, federal officers tasked with implementing the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had come to Wilkes Barre in pursuit of Thomas, who was claimed as a fugitive by slaveholder Isham Keith of Fauquier County, Virginia. The warrant for Thomas’s arrest, issued three days earlier on August 31, 1853, by notorious U.S. Commissioner Edward Ingraham of Philadelphia, was even endorsed by Circuit Court judge Robert C. Grier, before finding its way into the hands of three U.S. deputy marshals: George Wynkoop, John Jenkins and James Cresson. [2]

Heavily armed and bearing Ingraham’s warrant in hand, these three federal officers would make the 100-plus mile trek to Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania in a bid to arrest Thomas and carry him back to Philadelphia for a hearing before Commissioner Ingraham. While the slaveholder Keith did not accompany the group personally (it is unclear if he even made the trip to Philadelphia, or deputed an agent to act on his behalf via a power-of-attorney), two Virginians rounded out the slave catching posse: Dudley M. Pattie, a 30-year-old merchant from Warrington, Virginia, and 46-year-old James Settle, a clerk from Culpepper County, Virginia. Both knew the claimant personally and were brought along to identify Thomas.

The three deputies had arrived the previous evening, Friday, September 2, lodging at Gilchrist’s hotel, and were among the guests who took the early 6 o’clock breakfast the next morning. The two servers on staff that morning–Henry L. Patton and Thomas, both African Americans–waited on them. After dining, the three officers moved down the hall to the bar room, where they congregated with Pattie and Settle, ironing out the arrangements for the arrest. Pattie was to approach and identify Thomas, and the deputies would move in fast and arrest the waiter. Minutes later, they emerged, “walking rapidly” down the hallway, just as innkeeper Peter McCartney Gilchrist was sitting down to eat his breakfast. Gilchrist “supposed they were persons who had been stopping about town, and wanted breakfast to go with the stages,” though they ignored his friendly overture and rushed past him. Approaching Thomas from behind as the waiter was pouring coffee, Pattie took hold of his right shoulder, declaring, “This is the boy I require you to take under the warrant.” [3]

In an instant, Wynkoop, Crossen and Jenkins lunged, hurling Thomas to the floor, though their efforts to handcuff the alleged freedom seeker failed twice. In the meantime, Thomas grabbed hold of a carving knife, around the same time as Settle entered the room. Thomas “immediately recognized Mr. Settle,” according to Pattie, and “made a desperate effort to strike him with the point of the knife,” though in the melee Thomas’s arm was hit, and only the handle of the knife struck Settle. Still, it was enough to cause “serious injury upon his elbow,” and frighten the Virginian. He later told Commissioner Ingraham that the alleged escapee “made a desperate lunge at me with it [the knife] and could, I believe, have killed me but for Jenkins and Pattie, who caught his hand.” Even five weeks later, Settle groused that “the soreness has not yet left” his arm. When Jenkins and Pattie wrested the carving knife from Thomas’s hand, he procured a fork, and subsequently “a small breakfast knife,” and then used the handcuff the federal officers had attempted to fasten on his wrist to deliver a blow to Cresson, leaving the deputy marshal bleeding “copiously” from his head. With Cresson wounded, Thomas struggled out the door–the moment Henry Pettibone observed from his perch three floors up–wrestled free of the deputies’ grasp, and charged into the Susquehanna River, even as the officers fired at him. Standing in the river, as the puzzled posse conferred on the bank, Thomas defiantly declared that he would not be taken alive. Soon, the reports of gun fire drew out a large concourse of shocked local residents, who reproached the officers verbally, if not with physical force. [4]

As the five men struggled with Thomas–both in the dining room and along the banks of the Susquehanna–the federal officers drew upon one of the 1850 law’s more controversial features, situated within Section 5, which empowered the deputies to “summon and call to their aid the bystanders, or posse comitatus of the proper county, when necessary.” Such a formal call would hardly have been necessary in the slaveholding states, where draconian slave codes (laws enacted at the state level) and the relatively consistent cooperation lent by white southerners writ large, helped to form what Walter Johnson has termed the “carceral landscape.” That is, the white populace, stirred by fears of violent slave insurrections as well as the security of their own human property, could generally be counted on to police anyone who looked like a potential escapee–engendering a landscape of constant peril and heightened vulnerability for the freedom seeker. Yet that was anything but the case in the free states, where increasingly African Americans took violent stands against slaveholders and federal deputies tasked with arresting them, and vigilance operatives–both black and white–often helped to conceal their location. The 1850 law’s principal author, Virginia senator James Mason, spoke to precisely this disorienting reality (that is, disorienting for slaveholders) when he offered up this analogy of locating a freedom seeker who had escaped onto free soil: “you may as well go down into the sea, and endeavor to recover from his native element a fish which had escaped from you, as expect to recover such fugitive.” In the free states, Mason grumbled, “every difficulty is thrown in the way by the population to avoid discovery of where he is, and after this discovery is made, every difficulty is thrown in the way of executing process upon him.” Thus when either Wynkoop, Jenkins or Cresson invoked the provision in Section 5–and cried to the innkeeper Gilchrist, who was still in the dining room, “We are United States officers and we command assistance”–they were demanding help from a populace not committed to upholding a slave regime, a populace they could be sure would come enthusiastically to their aid. Even though the text of the 1850 law decreed that “all good citizens are hereby commanded to aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law, whenever their services may be required,” this was the design imprinted on the statute book, not necessarily the reality on the ground. [5]

The Virginian Dudley Pattie, reared in a slave society and its mode of community surveillance, clearly carried north with him some set of expectations about the support he and his posse could expect, however misplaced those assumptions proved to be. Some six weeks later, when deposed before Commissioner Ingraham, Pattie chafed that even as “the Marshals summoned the bystanders… without distinction, to render assistance,” only he and fellow Virginian Settle answered their call. There was Gilchrist, the innkeeper, who by his own account only halfheartedly attempted to subdue Thomas, before the waiter nearly landed a blow on his employer, prompting Gilchrist to beat a hasty retreat into the nearby bar room. Then 38-year-old David Seaman entered, and evaded the marshal’s call by pleading a “lame back,” and with a rather salty retort to one of the federal officers: “I told him I had enough to do to take care of myself.” (Patton, the other waiter, remembered Seaman’s reply differently: “If you five can’t take him,” Seaman reportedly said, “we won’t help you.”) Still, Seaman proved mildly acquiescent, if rough around the edges–he, along with another local, 40-year-old merchant Francis L. Bowman–led Cresson to Sheriff William Palmer’s office. However, Palmer was unsympathetic with posse’s mission or claims to federal authority, declaring that “he had other business besides taking n—rs.” Pattie, unaware of the sheriff’s stance, expected assistance from local authorities. When he eyed a boat manned by a dozen men down the river, he assumed it was the sheriff “coming to the assistance of the Marshal,” and returned to Gilchrist’s, where he confidently assured one spectator “that all was right–believing that if the boy had not escaped from the hands of the Marshal, that the Sheriff had rendered timely assistance.” [6]

Deposition of William C. Gildersleeve, the Wilkes Barre resident who helped bring charges against Commissioner Ingraham’s deputies. (RG 21, National Archives, Philadelphia)

Instead, Sheriff Palmer was fielding requests from William Gildersleeve, a 57-year-old merchant and abolitionist. Together with Judge Oristus Collins, a local lawyer, Gildersleeve had been pacing the banks of the river, angrily demanding the names of the three deputy marshals. Collins, who was “apparently much excited” was observed “talking with the officers, with a paper in his hand… asking questions and making memoranda.” Later, Jonathan Slocum, a 38-year-old attorney, eyed Gildersleeve at Sheriff Palmer’s office, “urging the sheriff to execute a warrant”–for the arrest of the three deputies. By his own admission, Gildersleeve had not witnessed the events that unfolded along the riverbank–including when the deputies fired at Thomas–though he swore out an affidavit that buttressed the warrant of arrest for the three deputies on charges of inciting riot and assault and battery upon Thomas. When the posse, sensing the antipathy of the local residents, beat a hasty retreat, Gildersleeve convinced Sheriff Palmer to telegraph the warrant to the nearby town of Hazleton, where they were briefly detained. However, the constable in Hazleton was “overawed by such pompous U.S. officers,” according to one account, and the party was released and proceeded back to Philadelphia. Yet learning of the case–which garnered headlines expressing shock and outrage throughout the northern press–two Philadelphia anti-slavery lawyers, one of whom was the noted David Paul Brown–journeyed to Wilkes Barre and entered Gildersleeve’s store several weeks after the incident. The two men introduced themselves, and armed with additional facts (including the deputies’ actual names) laid out evidence for another warrant of arrest. This time, scarcely a month after the botched arrest, on Tuesday, October 4, a warrant of arrest from Wilkes Barre magistrate Gilbert C. Burrows was served upon Jenkins and Cresson, who were imprisoned under state law in Philadelphia. (Wynkoop was out of town at the time). The two beleaguered deputies immediately petitioned Justice Robert Grier for a writ of habeas corpus, insisting that “all the acts done by them were done under the authority of the warrant issued by the said Commissioner.” [7]

From October 1853 onwards, the case took a number of twists and turns. Magistrate Burrows’s October warrant was tossed aside by a furious Justice Grier. In the habeas corpus hearing for Cresson and Jenkins, Grier held no punches, seething: “If any tuppenny magistrate, or any unprincipled interloper can come in, and cause to be arrested, the officers of the United States, whenever they please, it is a sad state of affairs.” In a portion of the draft of his decision that was crossed out, Grier honed in on precisely why the legal retaliation directed at Jenkins and Cresson carried with it alarming implications not only for federalism, but the practical enforcement of the 1850 law. There was “no more unpleasant duty imposed upon the courts & officers of the United States than that of arresting and deporting fugitives,” Grier noted, taking stock of the impact of violent resistance led by African Americans, and freedom seekers in particular (such as Thomas). Alleged escapees were “exhorted & encouraged to resist the officers unto death, and helped to escape,” as “mobs of unprincipled persons” also “frequently endeavor to evade [the law]…. by abusing … the process of the state court… by persecuting the officers of the law have been compelled to perform a most unpleasant & dangerous duty.” Grier discharged both Cresson and Jenkins. [8]

Little time elapsed before a grand jury in Luzerne County found a true bill against all three deputies for riot and assault and battery in November 1853, though an unspecified “defect” gummed up the proceedings. Undeterred, proceedings for their arrest continued, and on January 31, 1854, Pennsylvania State Supreme Court Justice Jeremiah S. Black issued a capias ad respondendum, a legal mechanism used to bring a defendant to answer for a civil action. As a result, the three deputies were arrested in Philadelphia on February 6, 1854, and held on $5,000 bail each. Jenkins, Cresson and now Wynkoop petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus, only this time their case was brought before District Court judge John K. Kane. Like Grier, Kane discharged the three men eight days later on February 14, 1854. In the intervening months, another grand jury in Luzerne County indicted the three men on the same charges, landing them in jail for a third time, before Judge Kane discharged them again in early May 1854. While that marked an end to the case (some nine months after the attempted arrest), a disgruntled Kane revealed something of the stress such legal retaliation placed on the federal courts’ already threadbare enforcement apparatus, which was straining to meet the demands of the 1850 law. “If a Marshal of the United States, in his efforts to execute process, issued from the Federal courts, is to be compelled constantly to suffer and combat with annoyances like this, his office becomes anything but a sinecure,” Kane wrote in his decision, “and in time it will be difficult to ensure the faithful performance of such duties.” [9]

Crucially, the legal harassment of Jenkins, Crossen and Wynkoop did not occur in isolation. This next post contextualizes this case with other instances of legal retaliation against the deputies tasked with executing U.S. commissioners’ warrants of arrest under the 1850 law.

[1] Deposition of Henry Pettibone, October 12, 1853, United States ex relat. Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, Entry 42-E-11-8.1 and 42-E-11-9.8, Box 1, Habeas Corpus Files, 1848-1862, Record Group 21, National Archives, Philadelphia. [2] Warrant of Arrest for William Thomas, August 31, 1853, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; All three deputies were regular officers of the federal courts, not special appointees under the law. Jenkins owed his appointment to the regular U.S. Marshal, Francis M. Wynkoop, who had taken advantage of a law passed by Congress in February 1853, authorizing marshals to appoint “such a number of persons, not exceeding five, as the judges of their respective courts shall determine, to attend upon the grand and other juries, and for other necessary purposes,” and receive $2 per day for their services. On May 19, 1853, Marshal Wynkoop had written federal District Court judge John K. Kane, who authorized the appointment of three deputies or bailiffs–among those appointed was Jenkins, on June 10, 1853. See Francis M. Wynkoop to the Honorable the Judges of the Circuit Court of the United States in and for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, May 19, 1853, John Jenkins Appointment, June 10, 1853, Entry 42-E-133, Box 1, Appointment Papers, Record Group 21, National Archives, Philadelphia; and The Statutes at Large and Treaties of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1845-1873), 10:161-169, [WEB]. Later in June 1853, Jenkins and Cresson, denoted as “deputies Marshals,” arrested a German man for watch smuggling in Philadelphia. See “Charged with Smuggling,” Philadelphia Daily Pennsylvanian, July 1, 1853. [3] Depositions of Peter McCartney Gilchrist and Dudley M. Pattie, October 12-13, 1853, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; Depositions of George Wynkoop and Henry L. Patton, in “The WilkesBarre Case—The Testimony,” Pennsylvania Freeman, October 20, 1853. [4] Deposition of James Settle, October 13, 1853, Box 3, Habeas Corpus Cases, 1791-1915, Record Group 21, National Archives, Philadelphia; Depositions of George Wynkoop and Henry L. Patton, in “The WilkesBarre Case—The Testimony,” Pennsylvania Freeman, October 20, 1853. [5] Deposition of Peter McCartney Gilchrist, October 12, 1853, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, Lillian Goodman Law Library, The Avalon Project, Yale Law Library, [WEB]; Appendix to Cong. Globe, 31st Cong., 1st sess., 1583 (1850), [WEB]; For the “carceral landscape,” see Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 209-243. [6] Depositions of Peter McCartney Gilchrist, Dudley M. Pattie, David Seaman and Francis L. Bowman, October 12-13, 1853, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; Deposition of Henry L. Patton, in “The WilkesBarre Case—The Testimony,” Pennsylvania Freeman, October 20, 1853. [7] Depositions of Francis L. Bowman, Henry Pettibone, Jonathan Slocum and William Gildersleeve, October 12-13, 1853, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; James Cresson and John Jenkins Petition, [October 4, 1853], To the Honorable Robert C. Grier, Judge of the Circuit Court of the United States, Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia; “Cruelty and Bloodshed,” Cleveland, OH Leader, September 9, 1853; “The Wilkes Barre Slave Case–Arrest of the Deputy Slave Catchers,” Pennsylvania Freeman, October 13, 1853. [8] “The Wilkes Barre Slave Case–Arrest of the Deputy Slave Catchers,” Pennsylvania Freeman, October 13, 1853; Justice Robert C. Grier, Draft Opinion, [October 1853], Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, National Archives, Philadelphia. [9] Warrant of Arrest for James Cresson, John Jenkins, George Wynkoop and Isham Keith, January 31, 1854, United States ex relat. Jenkins & Cresson v. Chollet, Entry 42-E-11-8.1 and 42-E-11-9.8, Box 1, Habeas Corpus Files, 1848-1862, Record Group 21, National Archives, Philadelphia; Opinion of Judge John K. Kane, May 9, 1854, United States vs. Samuel Allen, Esq., Writ of Habeas Corpus, Entry 42-E-11-8.1 and 42-E-11-9.8, Box 1, Habeas Corpus Files, 1848-1862, Record Group 21, National Archives, Philadelphia; “True Bill Found,” Sunbury, PA American, November 19, 1853; “The Wilkesbarre Slave Case—Judge Kane,” Philadelphia Daily Pennsylvanian, May 10, 1854.