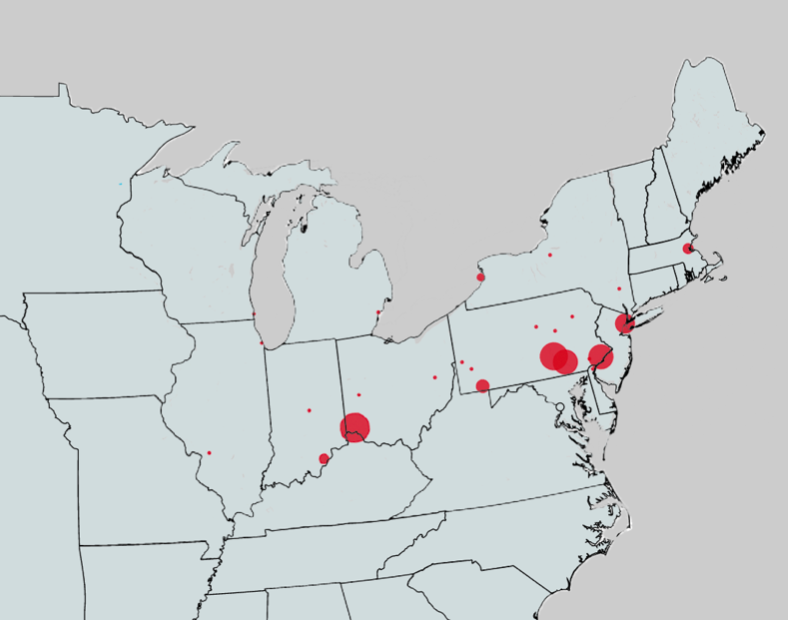

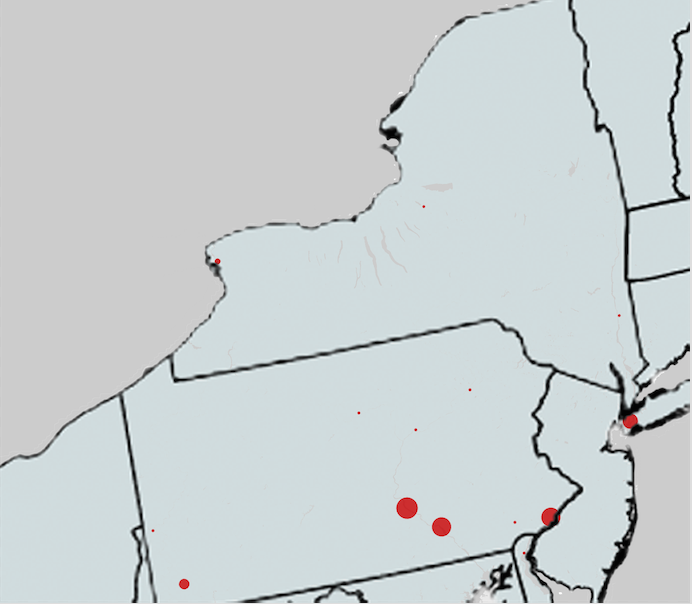

Having submitted my initial draft of chapter 1, which focuses on U.S. commissioners, it’s now time to map out my plans for chapter 2: a thematic chapter focused on the arrest process. Whereas chapter 1 focused on the totality of the enforcement landscape in the free soil north, and introduced the concept of a geography of enforcement, chapter 2 zooms in to the zones where the law was being enforced–against local opposition–to illuminate the struggle between federal officers, backed by pro-law shadow groups, and anti-slavery vigilance committees.

- Commissioners’ Deputies and Forming Posses

- I will first need to explain how U.S. commissioners appointed deputies to execute their warrants of arrest. Offering a brief background of Section 5 of the law will allow me to segue into how it was actually implemented on the ground. It will be crucial to expand on the concept of the pro-law shadow groups (from the Union Safety Committee in New York, to acquiescent local constables and independent slave catchers). In the law’s key enforcement hubs, such groups helped to prop up the weak federal rendition system.

- HISTORIOGRAPHY: In addition to touting the law’s enforcers as faithful and diligent, Stanley Campbell highlights the support the Pierce and Buchanan administration afforded commissioners’ deputies. [1] More recently, some scholars have stressed the power of anti-slavery resistance, especially the efforts of African Americans to resist the law throughout the border region. [2] In addressing the law’s arrest process, Robert Churchill has argued that by the late 1850s “the law quite literally came as a thief in the night,” observing how white northerners’ mounting antipathy towards the rendition process, coupled with the threat of violent resistance, pushed federal marshals and deputies to operate discreetly and often under the cover of darkness. [3]

- NEW EVIDENCE: In addition to the data set of arrests I have been compiling, I have uncovered new primary source material relating to two attempted arrests: North Carolina slaveholder Richard Riddick’s journey to Boston in January 1851, and several failed attempts to capture a freedom seeker named Lewis [4]; and over 30 pages of previously unpublished depositions of the failed arrest of William Thomas in the 1853 Wilkes Barre Case, drawn from the National Archives in Philadelphia. Together, these cases throw new light on the tenuousness of the arrest process and how anti-slavery activists managed to frustrate the process. In the attempted arrest of Lewis, the deputies expressed fear for their own safety (explicitly mentioning the actions of Boston’s anti-slavery vigilance committee) if they attempted to arrest Lewis. In the Wilkes Barre case, anti-slavery lawyers from Philadelphia’s revitalized vigilance committee helped charge the federal deputies for crimes under state law. For additional context, I have culled numerous trial transcripts (including penalty hearings), and found more than 20 depositions from deputies in other cases throughout the country, published contemporaneously in newspapers or pamphlets that shed light on the arrest process.

- HISTORIOGRAPHICAL INSIGHT: Harnessing the depositions of deputies, this section will illuminate how posses were formed, and the heavy reliance on specially deputized and temporary officers to help arrest alleged freedom seekers. The frequent use of temporary deputies who operated as part-time slave catchers (often simultaneously), blurred the lines between federal authority and private profiteering. Despite the law’s promises that federal officers would superintend the arrest of freedom seekers, a close analysis of the arrest process reveals that slaveholders still had to do a lot of the heavy lifting, often accompanying posses and at times physically assisting officers in subduing escapees, placing themselves in harm’s way. This helps explain why many slaveholders felt disgruntled with the law and federal officers, and grew disillusioned with the process over time. Posses also faced stiff resistance from northern communities, and free African Americans and freedom seekers in particular combatted arrest attempts with physical force, while anti-slavery lawyers often employed legal means to retaliate against deputies involved in enforcing the law. While Churchill has asserted that the law’s enforcers moved to covert tactics by the end of the decade, such controversial modes of arrest were already commonplace in the period between 1850-1854. The patterns of the arrest process, from hiring closed carriages to undertaking arrests at night, or in close proximity to rail lines, suggest the force and power of anti-slavery resistance was omnipresent in the minds of federal officials, whose tentativeness often irked claimants, even as the secretive mode of arrest outraged many northerners.

[1] Stanley Campbell,

The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 84, 87-89.

[2] Stanley Harrold,

Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Kellie Carter Jackson,

Force and Freedom: Black Politicians and the Politics of Violence (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

[3] Robert Churchill,

The Underground Railroad and the Geography of Violence in Antebellum America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 223.

[4] The attempted arrest of Lewis is mentioned in Gary Collison’s

Shadrach Minkins: From Fugitive Slave to Citizen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), though Lewis is not named, and Collison gleaned his information only from the reports published in the

Boston Commonwealth. The correspondence between Richard Riddick, the Union Safety Committee lawyer and Boston’s federal officials are replete with new insights into the case and the arrest process. These letters are briefly described in John Hope Franklin’s

A Southern Odyssey: Travelers in the Antebellum North (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1976), 153-154, though I plan to use the correspondence in considerably more detail in this chapter.