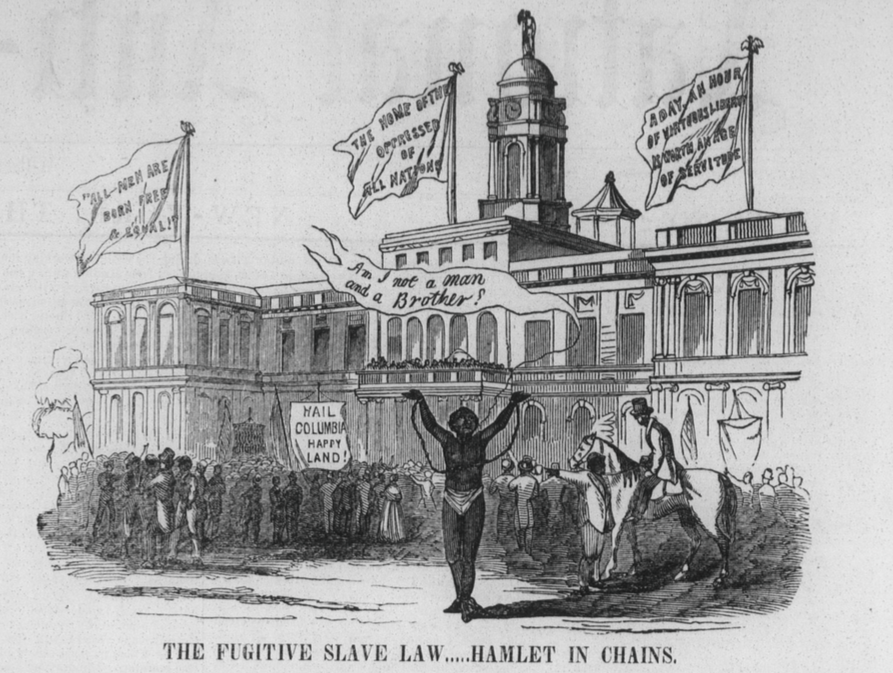

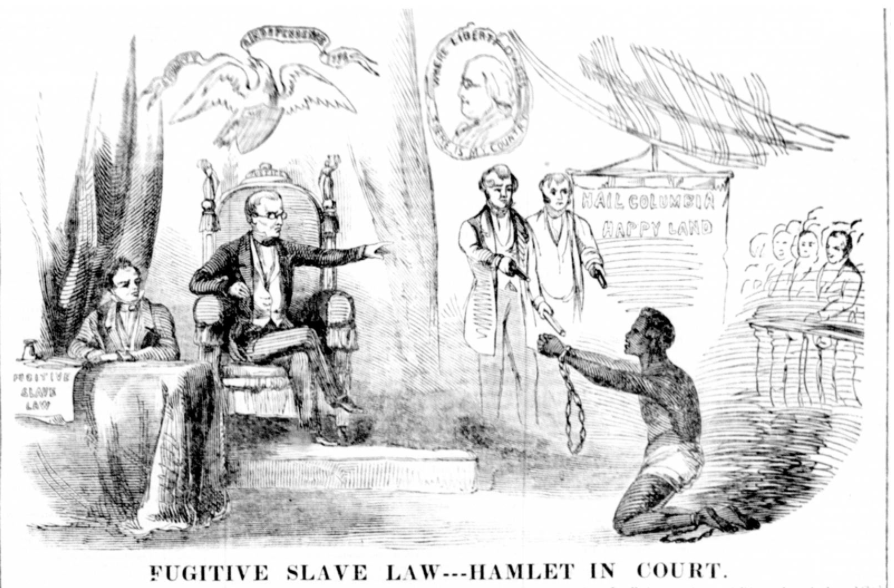

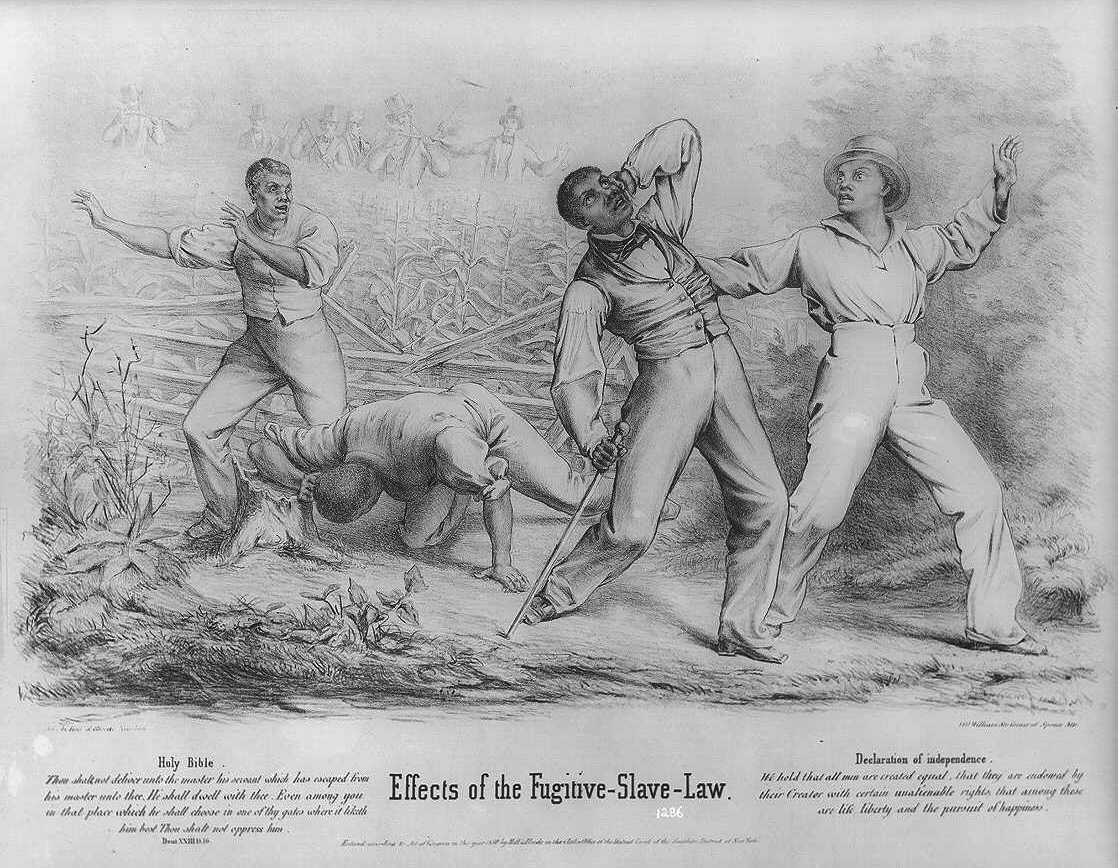

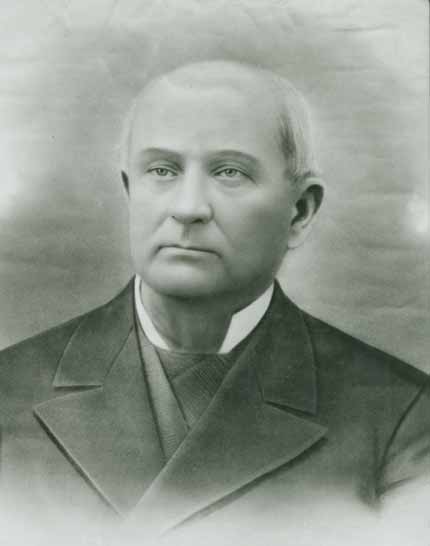

Known for the “urbanity of his manner,” Alexander Gardiner had already forged an impressive career at the age of 31. A lawyer, Princeton graduate, Clerk of the U.S. Circuit Court and U.S. Commissioner, he boasted a sterling resume, and was brother-in-law to a former U.S. president to boot. Yet his most enduring moment in the public eye would come on September 26, 1850–just days after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law–when, as Federal commissioner, he heard the first case under the controversial new statute. Remanding alleged fugitive James Hamlet to slavery, Gardiner saw his name tossed about in newspaper reports throughout the intensely divided nation, alternatively praised and denounced. Then, just months later, on January 16, 1851, the then 32-year-old lawyer abruptly fell ill. Five days later he was dead, of what one report described as a “bilious colic.” [1]

Gardiner hailed from a prominent New York family, which traced its lineage in the community of East Hampton back to 1639. Alexander’s father, the politician David Gardiner, had graduated from Yale in 1804–alongside John C. Calhoun–and served four years as a state senator in Albany. By 1843, the Gardiners had grown increasingly close to President John Tyler, and were traveling with the president aboard the steamboat USS Princeton in February 1844, when a sudden explosion killed David Gardiner and several members of Tyler’s cabinet. Yet in the months after the accident, the recently widowed Tyler continued to pursue his courtship of David Gardiner’s daughter, and Alexander’s doting sister, Julia Gardiner. [2]

After Julia’s marriage to the president in June 1844, Alexander Gardiner’s new connection to the First Family redefined his own social and political sense of self. During a visit to Washington in the fall of 1844, he eagerly described the thrill of attending a “very splendid” cabinet dinner alongside President Tyler, Julia, Secretary of State John Calhoun and other leading government luminaries. He became an enthusiastic supporter of the annexation of Texas, the top priority of his brother-in-law’s remaining months in the presidency, authoring a pro-annexation editorial–all with an eye, of course, to his own future prospects. “It may be of especial service to me,” Gardiner confided in his brother. [3] He was understandably elated when Tyler heaped praise on his editorial. “He came into my room with it in his hand,” Julia informed her brother, “saying ‘this piece of Alex’s is glorious–I had not conceived… he was so strong a writer–why his style is of the highest & richest kind!” A budding social and political alliance, Tyler appeared extremely fond of his substantially younger brother-in-law, so much so that some scholars have styled him an “unofficial Presidential aide.” For his part, Gardiner was even forced to issue a public disclaimer about his alleged influence-peddling. Yet his close relationship to the president was readily apparent to most observers. “Every once in a while he shakes his head and exclaims, Alex is destined to be a very distinguished man,” Julia penned. Tyler even floated the idea of Gardiner running for Congress, while Julia thought her brother better suited to be a diplomat. [4]

Unsurprisingly, the ambitious Gardiner soon set his sights on Federal patronage. He thought the post of U.S. consul at Liverpool, England to be “highly agreeable if I could get it,” but conceded that he would accept an appointment to the Navy Agency, “though it is scarcely of a caste to which I should aspire.” However, if he were to remain in New York, Gardiner wrote Julia, the Navy Agency would be “as good as any [office] here excepting the Clerkship of the U.S. Circuit Court.” [5] His suggestion did not go unheeded. Four months later, on April 11, 1845, Gardiner found himself “duly appointed by the Court” as clerk, a post that entailed a maximum yearly salary of $2,500. “Tomorrow I shall set about acquiring a practical knowledge of the duties,” Gardiner wrote in a lengthy epistle to Julia, “and next week probably enter upon the discharge of the office.” [6]

Yet as Gardiner settled in to his new duties, the New York Evening Post questioned the circumstances surrounding his elevation to the clerkship. “Alexander Gardiner is the brother-in-law of Mr. Tyler,” the paper reminded readers, noting that Gardiner’s appointment came at the hands of Justice Samuel Nelson, who had just been appointed by President Tyler in February 1845. While doubting that “a man of the elevated character of Judge Nelson would enter into any understanding with Mr. Tyler to provide for his relatives as a condition to his appointment,” the Evening Post speculated that Tyler and his allies had made Nelson “unconsciously… the instrument of fulfilling such a condition.” The appointment, the paper concluded, “is one of those things which we are sorry to see, but which harmonizes very well with the rest of Mr. Tyler’s conduct.” [7] In addition to his clerkship, sometime during 1845 Gardiner was appointed to (or assumed) the office of U.S. Commissioner. He would occupy both posts simultaneously until his sudden death six years later. [8]

Gardiner’s letters from 1845-1850 are replete with insights into the duties and daily routine of a U.S. Circuit Court officer in the antebellum period. While newspaper notices record the types of cases which came before Gardiner in his official capacity as U.S. Commissioner–ranging from a man who was charged with “opening a letter, and abstracting therefrom its contents,” to a hearing involving 12 African American sailors who were accused of “attempting to create a revolt”–Gardiner’s personal correspondence reveals how he negotiated the heavy, though infrequent workload that his new posts entailed. In July 1845, just months into his duties, Gardiner wrote of being “so constantly engaged in my business, that I have scarcely found any relaxation.” His life was dominated by brief periods of intense activity, punctuated by lengthy intervals when the court was not in session. “The next term of the Court will commence in about three weeks, and continue two or three months,” Gardiner wrote in 1848, “so that I am near a season of pretty active employment.” [9]

While historians have overlooked Gardiner’s close relationship to John Tyler, the former president’s views undoubtedly influenced Gardiner’s own outlook on the contentious 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. In February 1850, shortly after the compromise measures were first unveiled for debate, the Virginia slaveholder wrote his brother-in-law a lengthy missive outlining his views on the sectional divide. “The slave-holding states are deeply and profoundly excited,” penned Tyler, “by the constant annoyance they have experienced and continue to experience, upon the slavery question.” The vaunted “compromises of the Constitution in regard to fugitives from labor,” had been “despised and trampled upon in some quarters” of the North, the Virginian seethed, as “every conceivable impediment is cast in the way” of slave owners attempting to reclaim their “property.” [10] His prominent brother-in-law’s admonitions about Southern frustrations–and their potential implications for disunion– could not have been too far adrift from Commissioner Gardiner’s mind, when just months later he found himself adjudicating the first case under the contentious new law. After Gardiner made headlines for his role in the rendition of alleged fugitive James Hamlet, Tyler signaled his approbation. “Your name is becoming quite familiar to the lips of men around us,” the former president noted admiringly in December 1850. Gardiner’s “promptitude in deciding the first case which arose under the fugitive slave law,” Tyler wrote to another relative, had “inspired the whole South with confidence.” Praising Gardiner’s enforcement of the law, in the waning days of 1850 Tyler predicted that calmer waters lay ahead. “I think matters are looking better for the country,” he wrote. “The quiet in Congress so far is producing strong hopes that the storm is over.” [11]

With the passage of the new Fugitive Slave Law, the fall of 1850 was a particularly hectic time for Gardiner. In his capacity as U.S. Commissioner, the 31-year-old heard the Hamlet Case in late September. Yet in his role as clerk of the Circuit Court, Gardiner was tasked with, among other administrative functions, drafting and sending out a flurry of appointments from the court in a bid to meet the new law’s demands for an increased number of U.S. Commissioners. “At present my business is very pressing,” Gardiner scribbled in a hasty October 23 note addressed to Julia, without delving into any details. [12] The day before, on October 22, Gardiner had dispatched one of the many new appointments to Samuel E. Johnson, a local judge from Kings County, New York. Johnson, however, not only refused the office of U.S. Commissioner, but authored a lengthy rebuttal addressed to Gardiner, which he also leaked to the press. Politely worded but barbed nonetheless, Johnson declined the commissionership, citing a “serious doubt of the constitutionality of such an appointment.” Moreover, he insisted, serving as a U.S. Commissioner could “conflict” with his duties as a county judge, especially if a writ of habeas corpus was brought before him on behalf of an alleged fugitive. A Vermont newspaper picked up the story, noting with glee that Johnson had declined the appointment from “Slave Catcher-General Alexander Gardiner.” [13]

Gardiner’s dual role as clerk and commissioner resurfaced during another fugitive case that unfolded in the city in December 1850. Attempting to thwart the rendition of alleged fugitive Henry Long, anti-slavery lawyers questioned the credentials of Charles Hall, the presiding commissioner in the case. Joseph L. White, one of the anti-slavery attorneys, alleged that Hall “holds his office, he believes, under an old rule of the Court, that the Clerk of the Court shall be a Commissioner, as also shall the Deputy Clerk appointed by him.” Yet under Section 1 of the new law, White argued, appointments were to come directly from the Circuit Court itself. Hall was Gardiner’s deputy clerk, White observed, “and has not received his appointment from the Court,” which meant that he was “not a Commissioner under the law of 1850.” New York’s contingent of anti-slavery activists fumed that Hall, who reportedly “had resided in the city but two weeks, as clerk to Commissioner Gardiner,” was assuming the authority of a U.S. Commissioner. White’s narrow and shaky legal argument was enough to stymie the hearing, until a marshal reappeared “bearing a certificate of Mr. Gardiner, Clerk of the United States Circuit Court, that Mr. Hall is a Commissioner of said Court.” Yet when the marshal handed the certificate to White, the anti-slavery lawyer observed that the “seals were still wet,” exclaiming that the certificate was hastily produced “for the occasion.” [14] Despite the protests of White and others, Long was remanded to slavery.

As a whole, Gardiner’s correspondence offers crucial insight into the daily activities of U.S. Circuit Court officers, while also revealing the young lawyer’s close ties to his noted brother-in-law. Scholars of the 1850 law, as well as the small coterie of Tyler biographers, have neglected their relationship and its significance for both men’s views on the 1850 statute. [15] Writing from his Virginia home in February 1851, Tyler poured out his private grief onto paper. “To me he was almost every thing in connexion with my worldly affairs,” the ex-president mourned, intimating that Gardiner was in the process of crafting his memoirs to “put history right in regard to me.” Yet beyond the “great loss” Tyler felt personally, he regarded Gardiner’s sudden death as a “public calamity,” citing his “promptitude” in enforcing the 1850 law. [16]

[1] “Death of Mr. Commissioner Gardiner,” New York

Herald, January 23, 1851.

[2] Curtiss C. Gardiner (ed.),

Lion Gardiner, and His Descendants, 1599-1890 (St. Louis: A. Whipple, 1890), 149, [

WEB]; Also see Molly McClain, “David Lion Gardiner: A Yankee in Gold Rush California, 1849-1851,”

The Journal of San Diego History 62:3-4 (Summer/Fall 2015): 131-158, [

WEB].

[3] Alexander Gardiner to My Dear Brother, undated [1844], Series IV, Box 14, Folder 368, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Family Papers, Archives, Yale University.

[4] Julia Gardiner Tyler to Dear Alexander, December 8, 1844, Series IV, Box 14, Folder 360, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Family Papers, Yale University; Howard Gotlieb and Gail Grimes, “President Tyler and the Gardiners: A New Portrait,”

The Yale University Library Gazette 34:1 (July 1959): 3-5.

[5] Alexander Gardiner to My Dear Sister, January 8, 1845, Series II, Box 6, Folder 193, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Papers, Yale University.

[6] Alexander Gardiner to My Dear Sister, April 11, 1845, Series II, Box 6, Folder 193, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Papers, Yale University.

[7] “Appointment in the United States Circuit Court,” New York

Evening Post, April 15, 1845; “Appointed Clerk,” Baltimore

Daily Commercial, April 16, 1845.

[8] Gardiner was mentioned in his capacity as U.S. Commissioner in February 1846, but obituaries at the time of his 1851 death stated that he had held the commissionership since 1845. See “The Indiana Rubber Case–to Manufacturers,” New York

Tribune, February 27, 1846; “Death of Mr. Commissioner Gardiner,” New York

Herald, January 23, 1851.

[9] “United States Commissioner’s Office,” New York

Herald, January 26, 1849; “United States Commissioner’s Office,” New York

Herald, April 13, 1849; Alexander Gardiner to My Dear Sister, July 9, 1845, Gardiner to unidentified correspondent, [1848], Series II, Box 6, Folder 193, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Papers, Yale University.

[10] John Tyler to Alexander Gardiner, February 4, 1850, Tyler Family Papers, Special Collections, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, [

WEB].

[11] Tyler to Gardiner, December 27, 1850, Tyler Family Papers, Special Collections, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, [

WEB]; Tyler to David L. Gardiner, February 12, 1851, Tyler Family Papers, Special Collections, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, [

WEB].

[12] Alexander Gardiner to Sister, October 23, 1850, Series II, Box 6, Folder 193, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Family Papers, Yale University.

[13] Samuel E. Johnson to Alexander Gardiner, October 26, 1850, Series 4, Box 14, Folder 363, MS 230, Gardiner-Tyler Family Papers, Yale University; “Declines the Honor,” Burlington, VT

Courier, November 14, 1850; Johnson’s letter was published the same day, in “Another Refusal of the Appointment of United States Commissioner,” New York

Evening Post, October 26, 1850.

[14] “Alleged Slave Case,” New York

Tribune, December 28, 1850;

Annual Report of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, Presented at New-York, May 6, 1851 (New York: William Harned, 1851), 26, [

WEB].

[15] See Edward P. Crapol,

John Tyler: The Accidental President (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006); Gary May,

John Tyler (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2008).

[16] Tyler to David L. Gardiner, February 12, 1851, Tyler Family Papers, Special Collections, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, [

WEB].