The Battle of Ares and Athena (21.391-414)

May 16, 2014

In Book 21, as Achilles clogs the Scamander with corpses, the gods begin fight one another as well. In this scene Ares and Athena hit each other and brag about it like squabbling children, says Mickey Galamba. He compares the appeal of such humorous scenes among the gods to that of contemporary celebrity gossip magazines in which we are treated to witnessing the undignified doings of superior beings. Iliad 21.391-414, discussed, translated, and read aloud in Greek by Mickey Galamba.

Ares, the shield piercer, began. He first attacked Athena, having his bronze spear in hand, and he spoke with words of reproach:

“Why, dog-fly, do you once again set strife upon the gods with your furious audacity? Why has your bold spirit compelled you to do this? Do you not remember how you prompted Diomedes, son of Tydeides, to wound me, or how you yourself took up your spear in the sight of all, drove straight for me and pierced my fair flesh? I think now you will pay for what you have done.”

Thus speaking, he struck the terrible, tassled aegis, which not even the lightening of Zeus can pierce. This furious Ares struck with his long sword. Athena, forced back, picked up a stone, rough and jagged, with her massive hand, which earlier men placed in the field as a boundary stone: She hit Ares with this on the neck, and loosed his limbs. Falling, he covered seven plethra, his hair became covered in dust, and his armor clanged around him. Pallas Athena laughed, and vaunting over him she addressed him with winged words:

“Fool! You have obviously never noticed how much mightier I am than you, since you are now attempting to match me in strength. Keep it up and you might fulfil the curses of your mother. She is angry and schemes against you because you abandoned the Achaeans and are helping the insolent Trojans.”

ἦρχε γὰρ Ἄρης

ῥινοτόρος, καὶ πρῶτος Ἀθηναίῃ ἐπόρουσε

χάλκεον ἔγχος ἔχων, καὶ ὀνείδειον φάτο μῦθον:

τίπτ’ αὖτ’ ὦ κυνάμυια θεοὺς ἔριδι ξυνελαύνεις

θάρσος ἄητον ἔχουσα, μέγας δέ σε θυμὸς ἀνῆκεν; 395

ἦ οὐ μέμνῃ ὅτε Τυδεί̈δην Διομήδε’ ἀνῆκας

οὐτάμεναι, αὐτὴ δὲ πανόψιον ἔγχος ἑλοῦσα

ἰθὺς ἐμεῦ ὦσας, διὰ δὲ χρόα καλὸν ἔδαψας;

τώ σ’ αὖ νῦν ὀί̈ω ἀποτισέμεν ὅσσα ἔοργας.

ὣς εἰπὼν οὔτησε κατ’ αἰγίδα θυσσανόεσσαν 400

σμερδαλέην, ἣν οὐδὲ Διὸς δάμνησι κεραυνός:

τῇ μιν Ἄρης οὔτησε μιαιφόνος ἔγχεϊ μακρῷ.

ἣ δ’ ἀναχασσαμένη λίθον εἵλετο χειρὶ παχείῃ

κείμενον ἐν πεδίῳ μέλανα τρηχύν τε μέγαν τε,

τόν ῥ’ ἄνδρες πρότεροι θέσαν ἔμμεναι οὖρον ἀρούρης: 405

τῷ βάλε θοῦρον Ἄρηα κατ’ αὐχένα, λῦσε δὲ γυῖα.

ἑπτὰ δ’ ἐπέσχε πέλεθρα πεσών, ἐκόνισε δὲ χαίτας,

τεύχεά τ’ ἀμφαράβησε: γέλασσε δὲ Παλλὰς Ἀθήνη,

καί οἱ ἐπευχομένη ἔπεα πτερόεντα προσηύδα:

νηπύτι’ οὐδέ νύ πώ περ ἐπεφράσω ὅσσον ἀρείων 410

εὔχομ’ ἐγὼν ἔμεναι, ὅτι μοι μένος ἰσοφαρίζεις.

οὕτω κεν τῆς μητρὸς ἐρινύας ἐξαποτίνοις,

ἥ τοι χωομένη κακὰ μήδεται οὕνεκ’ Ἀχαιοὺς

κάλλιπες, αὐτὰρ Τρωσὶν ὑπερφιάλοισιν ἀμύνεις.

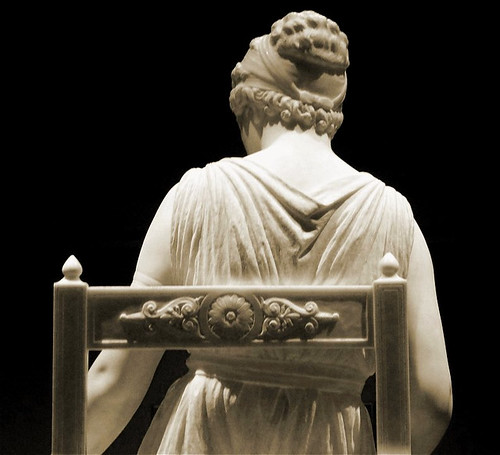

Image: Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), “The Combat of Ares and Athena,” 1771. Louvre Museum.

The Scream of Achilles (18.217-238)

May 16, 2014

Earlier on in the epic the action unfolds in mostly naturalist terms, as C.S. Lewis emphasizes in his discussion of Homer’s style. In the later parts of the poem, elements of pure fantasy start to appear, as in this section where men are killed solely by the wrath in Achilles’ scream. Sarah Eisen argues here that the presence of a complex simile in this passage marks it as a crucial turning point in the plot. Iliad 18.217-238, discussed, translated, and read in Greek by Sarah Eisen.

Standing there he shouted, and Pallas Athena shouted clearly from afar, and incited unspeakably great uproar in the Trojans.

It was like the brilliant peel of a trumpet, when it is blasted by the life-destroying enemies who surround the city, thus was at this time the remarkable cry of Achilles. But when they certainly perceived the blasting voice of Achilles, the souls in all of them were stirred. Even the fair-maned horses turned back the chariots, for in their hearts they forebode pain. Charioteers were astounded, when they saw the tireless and terrible fire blazing above the head of the greathearted Achilles. For the grey-eyed goddess Athena kindled the fire.

Thrice godlike Achilles bellowed greatly over the trench, thrice were the famous Trojans and allies panic-stricken. Then and there 12 great men were destroyed amidst their own chariots and spears. But gladly the Achaeans placed Patroclus on the bier, dragging him from the arrows. His companions stood around him, grieving. After them swift-footed Achilles followed, crying hot tears, when he saw his trusted comrade lying on the bier, he whom Achilles sent to war with his horses and chariot, but would not again be received going home.

ἔνθα στὰς ἤϋσ’, ἀπάτερθε δὲ Παλλὰς Ἀθήνη

φθέγξατ’: ἀτὰρ Τρώεσσιν ἐν ἄσπετον ὦρσε κυδοιμόν.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ἀριζήλη φωνή, ὅτε τ’ ἴαχε σάλπιγξ

ἄστυ περιπλομένων δηί̈ων ὕπο θυμοραϊστέων, 220

ὣς τότ’ ἀριζήλη φωνὴ γένετ’ Αἰακίδαο.

οἳ δ’ ὡς οὖν ἄϊον ὄπα χάλκεον Αἰακίδαο,

πᾶσιν ὀρίνθη θυμός: ἀτὰρ καλλίτριχες ἵπποι

ἂψ ὄχεα τρόπεον: ὄσσοντο γὰρ ἄλγεα θυμῷ.

ἡνίοχοι δ’ ἔκπληγεν, ἐπεὶ ἴδον ἀκάματον πῦρ 225

δεινὸν ὑπὲρ κεφαλῆς μεγαθύμου Πηλεί̈ωνος

δαιόμενον: τὸ δὲ δαῖε θεὰ γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη.

τρὶς μὲν ὑπὲρ τάφρου μεγάλ’ ἴαχε δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς,

τρὶς δὲ κυκήθησαν Τρῶες κλειτοί τ’ ἐπίκουροι.

ἔνθα δὲ καὶ τότ’ ὄλοντο δυώδεκα φῶτες ἄριστοι 230

ἀμφὶ σφοῖς ὀχέεσσι καὶ ἔγχεσιν. αὐτὰρ Ἀχαιοὶ

ἀσπασίως Πάτροκλον ὑπ’ ἐκ βελέων ἐρύσαντες

κάτθεσαν ἐν λεχέεσσι: φίλοι δ’ ἀμφέσταν ἑταῖροι

μυρόμενοι: μετὰ δέ σφι ποδώκης εἵπετ’ Ἀχιλλεὺς

δάκρυα θερμὰ χέων, ἐπεὶ εἴσιδε πιστὸν ἑταῖρον 235

κείμενον ἐν φέρτρῳ δεδαϊγμένον ὀξέϊ χαλκῷ,

τόν ῥ’ ἤτοι μὲν ἔπεμπε σὺν ἵπποισιν καὶ ὄχεσφιν

ἐς πόλεμον, οὐδ’ αὖτις ἐδέξατο νοστήσαντα.

Image: The Sosias Painter, “Achilles tending the wounded Patroklos,” late archaic period. Berlin, Antikenmuseen.

Homer’s description of the moment Patroclus dies is exquisitely poignant, argues Christina Errico, and Homer’s unusually familiar treatment of Patroclus leads the listener to form an emotional connection with him. Homer, Iliad 16.843-863, discussed, translated, and read in Greek by Christina Errico.

You answered him feebly, horseman Patroclus:

“You boast loudly now, Hector, for Zeus the son of Cronus and Apollo gave the victory to you;

They overpowered me easily; for they themselves took the armor from my shoulders.

Even if twenty such as you met me,

they all would have been destroyed, overpowered by my spear.

But deadly fate and the son of Leto killed me,

and of men, Euphorbus; but you come third in line to strip off my armor.

But I will tell you another thing, and you take it to heart:

surely you yourself will not live long, but already

death and strong fate loom over you,

ready to beat you down by the hands of brilliant Achilles, son of Aeacus.”

And so, as he was speaking in this way, the end of death came over him;

his soul, having flown from his limbs, went to Hades

mourning his fate, leaving behind his manliness and youth.

τὸν δ’ ὀλιγοδρανέων προσέφης Πατρόκλεες ἱππεῦ:

ἤδη νῦν Ἕκτορ μεγάλ’ εὔχεο: σοὶ γὰρ ἔδωκε

νίκην Ζεὺς Κρονίδης καὶ Ἀπόλλων, οἵ με δάμασσαν 845

ῥηιδίως: αὐτοὶ γὰρ ἀπ’ ὤμων τεύχε’ ἕλοντο.

τοιοῦτοι δ’ εἴ πέρ μοι ἐείκοσιν ἀντεβόλησαν,

πάντές κ’ αὐτόθ’ ὄλοντο ἐμῷ ὑπὸ δουρὶ δαμέντες.

ἀλλά με μοῖρ’ ὀλοὴ καὶ Λητοῦς ἔκτανεν υἱός,

ἀνδρῶν δ’ Εὔφορβος: σὺ δέ με τρίτος ἐξεναρίζεις. 850

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω, σὺ δ’ ἐνὶ φρεσὶ βάλλεο σῇσιν:

οὔ θην οὐδ’ αὐτὸς δηρὸν βέῃ, ἀλλά τοι ἤδη

ἄγχι παρέστηκεν θάνατος καὶ μοῖρα κραταιὴ

χερσὶ δαμέντ’ Ἀχιλῆος ἀμύμονος Αἰακίδαο.

ὣς ἄρα μιν εἰπόντα τέλος θανάτοιο κάλυψε: 855

ψυχὴ δ’ ἐκ ῥεθέων πταμένη Ἄϊδος δὲ βεβήκει

ὃν πότμον γοόωσα λιποῦσ’ ἀνδροτῆτα καὶ ἥβην.

τὸν καὶ τεθνηῶτα προσηύδα φαίδιμος Ἕκτωρ:

Πατρόκλεις τί νύ μοι μαντεύεαι αἰπὺν ὄλεθρον;

τίς δ’ οἶδ’ εἴ κ’ Ἀχιλεὺς Θέτιδος πάϊς ἠϋκόμοιο 860

φθήῃ ἐμῷ ὑπὸ δουρὶ τυπεὶς ἀπὸ θυμὸν ὀλέσσαι;

ὣς ἄρα φωνήσας δόρυ χάλκεον ἐξ ὠτειλῆς

εἴρυσε λὰξ προσβάς, τὸν δ’ ὕπτιον ὦσ’ ἀπὸ δουρός.

Image: Gavin Hamilton, “Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus,” 1760 – 1763. National Galleries Scotland

In a key scene near the end of the Iliad, King Priam beseeches Achilles to release the corpse of his son Hector. Simone Weil’s famous wartime reading of the poem, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force,” argues that Priam is just the object that Achilles rules over. Kaylin Bednarz challenges Weil’s reading of the passage, noting that she omitted a key Greek word in her translation. Homer, Iliad 24. 486-516, discussed, translated, and read aloud in Greek by Kaylin Bednarz.

“Godlike Achilles, remember your own father, who is of such an old age as I, on the deadly threshold of old age. It might be that his neighbors harass him, and there is no one to ward off war and ruin from him. But when hearing that you are alive he rejoices, and his days are full of hope that he will see his dear son coming from Troy; but I am completely doomed. I brought the bravest sons in broad Troy, but of them I say there is not one left. I had fifty when the sons of the Achaeans came; nineteen were from one womb. Women in the palace bore the others for me. Violent Ares cut the knees from under most of these sons. This was my only surviving son. He guarded the city and its people. You have recently killed him, as he guarded his fatherland, Hector. And so I have now come to the ships of the Achaeans, in order to ransom him from you; I bring a huge ransom. But respect the gods, Achilles, and take pity on him, remembering your own father. But I am even more pitiful; for I have suffered such things as no other mortal man on earth has, I have put to my face the hands of the man who killed my sons.” So he spoke; he stirred up in Achilles a longing to weep for his father. And so, grasping the old man by the hand he gently pushed him away. They both remembered. Priam, remembering man-slaying Hector, wept intensely, crouching at Achilles’ feet; but Achilles wept for his own father, and then for Patroclus. Their wailing stirred up the house. But when godlike Achilles had his fill of grieving and the longing for it left from his heart and body, he arose from his seat, and raised the old man by the hand, pitying his white head and white beard.

μνῆσαι πατρὸς σοῖο θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ’ Ἀχιλλεῦ,

τηλίκου ὥς περ ἐγών, ὀλοῷ ἐπὶ γήραος οὐδῷ:

καὶ μέν που κεῖνον περιναιέται ἀμφὶς ἐόντες

τείρουσ’, οὐδέ τίς ἐστιν ἀρὴν καὶ λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι.

ἀλλ’ ἤτοι κεῖνός γε σέθεν ζώοντος ἀκούων

χαίρει τ’ ἐν θυμῷ, ἐπί τ’ ἔλπεται ἤματα πάντα

ὄψεσθαι φίλον υἱὸν ἀπὸ Τροίηθεν ἰόντα:

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ πανάποτμος, ἐπεὶ τέκον υἷας ἀρίστους

Τροίῃ ἐν εὐρείῃ, τῶν δ’ οὔ τινά φημι λελεῖφθαι.

πεντήκοντά μοι ἦσαν ὅτ’ ἤλυθον υἷες Ἀχαιῶν:

ἐννεακαίδεκα μέν μοι ἰῆς ἐκ νηδύος ἦσαν,

τοὺς δ’ ἄλλους μοι ἔτικτον ἐνὶ μεγάροισι γυναῖκες.

τῶν μὲν πολλῶν θοῦρος Ἄρης ὑπὸ γούνατ’ ἔλυσεν:

ὃς δέ μοι οἶος ἔην, εἴρυτο δὲ ἄστυ καὶ αὐτούς,

τὸν σὺ πρῴην κτεῖνας ἀμυνόμενον περὶ πάτρης

Ἕκτορα: τοῦ νῦν εἵνεχ’ ἱκάνω νῆας Ἀχαιῶν

λυσόμενος παρὰ σεῖο, φέρω δ’ ἀπερείσι’ ἄποινα.

ἀλλ’ αἰδεῖο θεοὺς Ἀχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ’ ἐλέησον

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός: ἐγὼ δ’ ἐλεεινότερός περ,

ἔτλην δ’ οἷ’ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθόνιος βροτὸς ἄλλος,

ἀνδρὸς παιδοφόνοιο ποτὶ στόμα χεῖρ’ ὀρέγεσθαι.

ὣς φάτο, τῷ δ’ ἄρα πατρὸς ὑφ’ ἵμερον ὦρσε γόοιο:

ἁψάμενος δ’ ἄρα χειρὸς ἀπώσατο ἦκα γέροντα.

τὼ δὲ μνησαμένω ὃ μὲν Ἕκτορος ἀνδροφόνοιο

κλαῖ’ ἁδινὰ προπάροιθε ποδῶν Ἀχιλῆος ἐλυσθείς,

αὐτὰρ Ἀχιλλεὺς κλαῖεν ἑὸν πατέρ’, ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτε

Πάτροκλον: τῶν δὲ στοναχὴ κατὰ δώματ’ ὀρώρει.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεί ῥα γόοιο τετάρπετο δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς,

καί οἱ ἀπὸ πραπίδων ἦλθ’ ἵμερος ἠδ’ ἀπὸ γυίων,

αὐτίκ’ ἀπὸ θρόνου ὦρτο, γέροντα δὲ χειρὸς ἀνίστη

οἰκτίρων πολιόν τε κάρη πολιόν τε γένειον.

Image: Bertel Thorvaldsen, “Priam Pleads with Achilles for Hector’s Body,” 1868-1870.

Homer’s Divine Inspiration (Odyssey 8.487-498)

May 1, 2013

Solai Sanchez explores the Greek idea of poetry as divinely inspired, and poets as bestowers of immortality. In Book 8 of the Odyssey Odysseus praises the poet Demodocus by saying that he must have learned his craft from the Muse, or from Apollo. What does this mean, exactly? Odyssey 8.487-498 discussed, translated, and read aloud by Solai Sanchez.

“Δημόδοκ’, ἔξοχα δή σε βροτῶν αἰνίζομ’ ἁπάντων·

ἢ σέ γε Μοῦσ’ ἐδίδαξε, Διὸς πάϊς, ἢ σέ γ’ Ἀπόλλων·

λίην γὰρ κατὰ κόσμον Ἀχαιῶν οἶτον ἀείδεις,

ὅσσ’ ἕρξαν τ’ ἔπαθόν τε καὶ ὅσσ’ ἐμόγησαν Ἀχαιοί,

ὥς τέ που ἢ αὐτὸς παρεὼν ἢ ἄλλου ἀκούσας.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ μετάβηθι καὶ ἵππου κόσμον ἄεισον

δουρατέου, τὸν Ἐπειὸς ἐποίησεν σὺν Ἀθήνῃ,

ὅν ποτ’ ἐς ἀκρόπολιν δόλον ἤγαγε δῖος Ὀδυσσεὺς

ἀνδρῶν ἐμπλήσας, οἳ Ἴλιον ἐξαλάπαξαν.

αἴ κεν δή μοι ταῦτα κατὰ μοῖραν καταλέξῃς,

αὐτίκα καὶ πᾶσιν μυθήσομαι ἀνθρώποισιν,

ὡς ἄρα τοι πρόφρων θεὸς ὤπασε θέσπιν ἀοιδήν.”

Divine License (Iliad 21.342-355)

May 1, 2013

Morisseau_podcast_Greek112_2013

Will Morriseau argues that uses the gods to impose his own will on the poem. His freedom with the facts is “divine license,” and Homer himself is the only real deity in the work. Will discusses this idea in the context of a puzzling simile in Iliad 21, where Hephaestus is scorching the battlefield. Iliad 21.342-355, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Will Morriseau.

Ὣς ἔφαθ’, Ἥφαιστος δὲ τιτύσκετο θεσπιδαὲς πῦρ.

πρῶτα μὲν ἐν πεδίῳ πῦρ δαίετο, καῖε δὲ νεκροὺς

πολλούς, οἵ ῥα κατ’ αὐτὸν ἅλις ἔσαν, οὓς κτάν’ Ἀχιλλεύς·

πᾶν δ’ ἐξηράνθη πεδίον, σχέτο δ’ ἀγλαὸν ὕδωρ.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ὀπωρινὸς Βορέης νεοαρδέ’ ἀλωὴν

αἶψ’ ἀγξηράνῃ· χαίρει δέ μιν ὅς τις ἐθείρῃ·

ὣς ἐξηράνθη πεδίον πᾶν, κὰδ δ’ ἄρα νεκροὺς

κῆεν· ὃ δ’ ἐς ποταμὸν τρέψε φλόγα παμφανόωσαν.

καίοντο πτελέαι τε καὶ ἰτέαι ἠδὲ μυρῖκαι,

καίετο δὲ λωτός τε ἰδὲ θρύον ἠδὲ κύπειρον,

τὰ περὶ καλὰ ῥέεθρα ἅλις ποταμοῖο πεφύκει·

τείροντ’ ἐγχέλυές τε καὶ ἰχθύες οἳ κατὰ δίνας,

οἳ κατὰ καλὰ ῥέεθρα κυβίστων ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα

πνοιῇ τειρόμενοι πολυμήτιος Ἡφαίστοιο.

A Hero’s Best Friend (Odyssey 17.290-304)

May 1, 2013

The famous scene in which Argus, Odysseus’ faithful dog, recognizes Odysseus on his return and promptly expires, is more than just pathos, argues Lucy McInerney. It is also an opportunity for Homer to show the fortitude of Odysseus himself. In other recognition scenes, she points out, Odysseus is able to share his emotions with whoever it is that recognizes him. In the case of Argus, the only character in the whole epic to recognize Odysseus on sight, he has to turn away and pretend not to know him. Odyssey 17.290-304 discussed, translated, and read aloud by Lucy McInerney.

John Flaxman, Odysseus and Argos (1805) Engraving and etching on paper, Tate Gallery

ὣς οἱ μὲν τοιαῦτα πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἀγόρευον·

ἂν δὲ κύων κεφαλήν τε καὶ οὔατα κείμενος ἔσχεν,

Ἄργος, Ὀδυσσῆος ταλασίφρονος, ὅν ῥά ποτ’ αὐτὸς

θρέψε μέν, οὐδ’ ἀπόνητο, πάρος δ’ εἰς Ἴλιον ἱρὴν

ᾤχετο. τὸν δὲ πάροιθεν ἀγίνεσκον νέοι ἄνδρες

αἶγας ἐπ’ ἀγροτέρας ἠδὲ πρόκας ἠδὲ λαγωούς·

δὴ τότε κεῖτ’ ἀπόθεστος ἀποιχομένοιο ἄνακτος

ἐν πολλῇ κόπρῳ, ἥ οἱ προπάροιθε θυράων @1

ἡμιόνων τε βοῶν τε ἅλις κέχυτ’, ὄφρ’ ἂν ἄγοιεν

δμῶες Ὀδυσσῆος τέμενος μέγα κοπρίσσοντες·

ἔνθα κύων κεῖτ’ Ἄργος ἐνίπλειος κυνοραιστέων.

δὴ τότε γ’, ὡς ἐνόησεν Ὀδυσσέα ἐγγὺς ἐόντα,

οὐρῇ μέν ῥ’ ὅ γ’ ἔσηνε καὶ οὔατα κάββαλεν ἄμφω,

ἄσσον δ’ οὐκέτ’ ἔπειτα δυνήσατο οἷο ἄνακτος

ἐλθέμεν· αὐτὰρ ὁ νόσφιν ἰδὼν ἀπομόρξατο δάκρυ,

ῥεῖα λαθὼν Εὔμαιον, ἄφαρ δ’ ἐρεείνετο μύθῳ·

Women are not to be trusted, says the ghost of Agamemnon to Odysseus in the underworld in Book 11 of the Odyssey. Penelope is an exception, even he admits, while advising caution to Odysseus on his return home. Allison Hummel argues that this passage praising Penelope in the middle of the Odyssey is crucial to reminding Odysseus, and us, about the meaning of Odysseus’ great struggle to get home. Homer, Odyssey 11.440-456, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Allison Hummel.

Penelope. Detail of the statue by American sculptor Franklin Simmons

ὣς ἐφάμην, ὁ δέ μ᾽ αὐτίκ᾽ ἀμειβόμενος προσέειπε:

‘τῷ νῦν μή ποτε καὶ σὺ γυναικί περ ἤπιος εἶναι:

μή οἱ μῦθον ἅπαντα πιφαυσκέμεν, ὅν κ᾽ ἐὺ εἰδῇς,

ἀλλὰ τὸ μὲν φάσθαι, τὸ δὲ καὶ κεκρυμμένον εἶναι.

ἀλλ᾽ οὐ σοί γ᾽, Ὀδυσεῦ, φόνος ἔσσεται ἔκ γε γυναικός:

λίην γὰρ πινυτή τε καὶ εὖ φρεσὶ μήδεα οἶδε

κούρη Ἰκαρίοιο, περίφρων Πηνελόπεια.

ἦ μέν μιν νύμφην γε νέην κατελείπομεν ἡμεῖς

ἐρχόμενοι πόλεμόνδε: πάϊς δέ οἱ ἦν ἐπὶ μαζῷ

νήπιος, ὅς που νῦν γε μετ᾽ ἀνδρῶν ἵζει ἀριθμῷ,

ὄλβιος: ἦ γὰρ τόν γε πατὴρ φίλος ὄψεται ἐλθών,

καὶ κεῖνος πατέρα προσπτύξεται, ἣ θέμις ἐστίν.

ἡ δ᾽ ἐμὴ οὐδέ περ υἷος ἐνιπλησθῆναι ἄκοιτις

ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ἔασε: πάρος δέ με πέφνε καὶ αὐτόν.

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω, σὺ δ᾽ ἐνὶ φρεσὶ βάλλεο σῇσιν:

κρύβδην, μηδ᾽ ἀναφανδά, φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν

νῆα κατισχέμεναι: ἐπεὶ οὐκέτι πιστὰ γυναιξίν.

Fire and the Use of Simile (Iliad 21.8-16)

April 30, 2013

Near the climax of the Iliad, Achilles alone chases a large number of Trojans into the river Xanthos, where they take refuge, Homer says, like locusts take refuge in a river when they are being attacked with fire. Emily Drummond notes that the people of Cyprus are known to have actually used this method to combat locusts, but she points out that the simile also needs to be seen next to other similes in the immediate context where Achilles is compared to fire. Iliad 21.8-16, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Emily Drummond.

ἐς ποταμὸν εἰλεῦντο βαθύρροον ἀργυροδίνην,

ἐν δ’ ἔπεσον μεγάλῳ πατάγῳ, βράχε δ’ αἰπὰ ῥέεθρα,

ὄχθαι δ’ ἀμφὶ περὶ μεγάλ’ ἴαχον· οἳ δ’ ἀλαλητῷ

ἔννεον ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα ἑλισσόμενοι περὶ δίνας.

ὡς δ’ ὅθ’ ὑπὸ ῥιπῆς πυρὸς ἀκρίδες ἠερέθονται

φευγέμεναι ποταμὸν δέ· τὸ δὲ φλέγει ἀκάματον πῦρ

ὄρμενον ἐξαίφνης, ταὶ δὲ πτώσσουσι καθ’ ὕδωρ·

ὣς ὑπ’ Ἀχιλλῆος Ξάνθου βαθυδινήεντος

πλῆτο ῥόος κελάδων ἐπιμὶξ ἵππων τε καὶ ἀνδρῶν.

Chariot tactics in Homer (Iliad 4.297-309)

May 16, 2012

Chariots appear frequently in the Iliad, but Homer notoriously seems to have little idea of how they would actually be used in combat. Dan Plekhov points out the exception, a passage that does seem to describe realistic chariot tactics, and argues that it reflects memories of Mycenaean culture, not the experience of contemporary societies of Homer’s own day. Iliad 4.297-309, read, translated and discussed by Dan Plekhov.

ἱππῆας μὲν πρῶτα σὺν ἵπποισιν καὶ ὄχεσφι,

πεζοὺς δ’ ἐξόπιθε στῆσεν πολέας τε καὶ ἐσθλοὺς

ἕρκος ἔμεν πολέμοιο· κακοὺς δ’ ἐς μέσσον ἔλασσεν,

ὄφρα καὶ οὐκ ἐθέλων τις ἀναγκαίῃ πολεμίζοι. (300)

ἱππεῦσιν μὲν πρῶτ’ ἐπετέλλετο· τοὺς γὰρ ἀνώγει

σφοὺς ἵππους ἐχέμεν μηδὲ κλονέεσθαι ὁμίλῳ·

μηδέ τις ἱπποσύνῃ τε καὶ ἠνορέηφι πεποιθὼς

οἶος πρόσθ’ ἄλλων μεμάτω Τρώεσσι μάχεσθαι,

μηδ’ ἀναχωρείτω· ἀλαπαδνότεροι γὰρ ἔσεσθε. (305)

ὃς δέ κ’ ἀνὴρ ἀπὸ ὧν ὀχέων ἕτερ’ ἅρμαθ’ ἵκηται

ἔγχει ὀρεξάσθω, ἐπεὶ ἦ πολὺ φέρτερον οὕτω.

ὧδε καὶ οἱ πρότεροι πόλεας καὶ τείχε’ ἐπόρθεον

τόνδε νόον καὶ θυμὸν ἐνὶ στήθεσσιν ἔχοντες

Podcast: Play in new window | Download