The Arming of Patroclus (16.124-145)

May 16, 2014

Among the scenes of arming of heroes in the Iliad, the arming of Patroclus in Book 16 is unique in that pattern of aristeia that we come to expect after the arming scenes is suddenly broken, argues Olga Faccani. Patroclus not taking Achilles’ spear before going to battle stands for an incompleteness in the aristeia and forecasts his destruction. Iliad 16.124-145, discussed, translated, and read in Greek by Olga Faccani.

And so Achilles slapped his thighs and spoke to Patroclus:

“Stand up, divine Patroclus, master of horsemen;

I can see the fighting and the fire raging by the ships,

And may our enemies never take them:

We should not delay any further.

Quick, put on my armor, and I will gather the army.”

Thus spoke Achilles, and Patroclus armed himself in flashing bronze:

First he wore around his legs the stunning greaves,

Joined together with silver ankle-pieces;

Secondly, he fastened the breastplate around his chest,

The superb breastplate belonging to swift-footed Achilles, embroidered with stars.

Then, he threw the bronze sword, silver studded, around his shoulders,

and the sturdy massive shield.

On his strong head he then put the helmet,

Adorned with horse tail hair,

And its crest nodded terribly form above.

He finally seized two deadly spears,

which perfectly fitted his palms.

But he forgot the spear of noble Achilles,

That heavy, long and sturdy spear which none of the other Acheans could lift:

For Achilles alone managed to hold it.

That spear had been carved out of Peliaden ash,

From the peak of Mount Pelion,

And Chirion offered it to his dear father,

So that it could be the doom of many heroes.

αὐτὰρ Ἀχιλλεὺς

μηρὼ πληξάμενος Πατροκλῆα προσέειπεν: 125

‘ὄρσεο διογενὲς Πατρόκλεες ἱπποκέλευθε:

λεύσσω δὴ παρὰ νηυσὶ πυρὸς δηΐοιο ἰωήν:

μὴ δὴ νῆας ἕλωσι καὶ οὐκέτι φυκτὰ πέλωνται:

δύσεο τεύχεα θᾶσσον, ἐγὼ δέ κε λαὸν ἀγείρω.

ὣς φάτο, Πάτροκλος δὲ κορύσσετο νώροπι χαλκῷ. 130

κνημῖδας μὲν πρῶτα περὶ κνήμῃσιν ἔθηκε

καλάς, ἀργυρέοισιν ἐπισφυρίοις ἀραρυίας:

δεύτερον αὖ θώρηκα περὶ στήθεσσιν ἔδυνε

ποικίλον ἀστερόεντα ποδώκεος Αἰακίδαο.

ἀμφὶ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὤμοισιν βάλετο ξίφος ἀργυρόηλον 135

χάλκεον, αὐτὰρ ἔπειτα σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε:

κρατὶ δ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἰφθίμῳ κυνέην εὔτυκτον ἔθηκεν

ἵππουριν: δεινὸν δὲ λόφος καθύπερθεν ἔνευεν.

εἵλετο δ᾽ ἄλκιμα δοῦρε, τά οἱ παλάμηφιν ἀρήρει.

ἔγχος δ᾽ οὐχ ἕλετ᾽ οἶον ἀμύμονος Αἰακίδαο 140

βριθὺ μέγα στιβαρόν: τὸ μὲν οὐ δύνατ᾽ ἄλλος Ἀχαιῶν

πάλλειν, ἀλλά μιν οἶος ἐπίστατο πῆλαι Ἀχιλλεὺς

Πηλιάδα μελίην, τὴν πατρὶ φίλῳ πόρε Χείρων

Πηλίου ἐκ κορυφῆς, φόνον ἔμμεναι ἡρώεσσιν. 145

Image: The Euphronios Kater. Side B: Youths arming themselves. Ca. 515 BC. National Etruscan Museum, in the Villa Giulia in Rome.

In a key scene near the end of the Iliad, King Priam beseeches Achilles to release the corpse of his son Hector. Simone Weil’s famous wartime reading of the poem, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force,” argues that Priam is just the object that Achilles rules over. Kaylin Bednarz challenges Weil’s reading of the passage, noting that she omitted a key Greek word in her translation. Homer, Iliad 24. 486-516, discussed, translated, and read aloud in Greek by Kaylin Bednarz.

“Godlike Achilles, remember your own father, who is of such an old age as I, on the deadly threshold of old age. It might be that his neighbors harass him, and there is no one to ward off war and ruin from him. But when hearing that you are alive he rejoices, and his days are full of hope that he will see his dear son coming from Troy; but I am completely doomed. I brought the bravest sons in broad Troy, but of them I say there is not one left. I had fifty when the sons of the Achaeans came; nineteen were from one womb. Women in the palace bore the others for me. Violent Ares cut the knees from under most of these sons. This was my only surviving son. He guarded the city and its people. You have recently killed him, as he guarded his fatherland, Hector. And so I have now come to the ships of the Achaeans, in order to ransom him from you; I bring a huge ransom. But respect the gods, Achilles, and take pity on him, remembering your own father. But I am even more pitiful; for I have suffered such things as no other mortal man on earth has, I have put to my face the hands of the man who killed my sons.” So he spoke; he stirred up in Achilles a longing to weep for his father. And so, grasping the old man by the hand he gently pushed him away. They both remembered. Priam, remembering man-slaying Hector, wept intensely, crouching at Achilles’ feet; but Achilles wept for his own father, and then for Patroclus. Their wailing stirred up the house. But when godlike Achilles had his fill of grieving and the longing for it left from his heart and body, he arose from his seat, and raised the old man by the hand, pitying his white head and white beard.

μνῆσαι πατρὸς σοῖο θεοῖς ἐπιείκελ’ Ἀχιλλεῦ,

τηλίκου ὥς περ ἐγών, ὀλοῷ ἐπὶ γήραος οὐδῷ:

καὶ μέν που κεῖνον περιναιέται ἀμφὶς ἐόντες

τείρουσ’, οὐδέ τίς ἐστιν ἀρὴν καὶ λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι.

ἀλλ’ ἤτοι κεῖνός γε σέθεν ζώοντος ἀκούων

χαίρει τ’ ἐν θυμῷ, ἐπί τ’ ἔλπεται ἤματα πάντα

ὄψεσθαι φίλον υἱὸν ἀπὸ Τροίηθεν ἰόντα:

αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ πανάποτμος, ἐπεὶ τέκον υἷας ἀρίστους

Τροίῃ ἐν εὐρείῃ, τῶν δ’ οὔ τινά φημι λελεῖφθαι.

πεντήκοντά μοι ἦσαν ὅτ’ ἤλυθον υἷες Ἀχαιῶν:

ἐννεακαίδεκα μέν μοι ἰῆς ἐκ νηδύος ἦσαν,

τοὺς δ’ ἄλλους μοι ἔτικτον ἐνὶ μεγάροισι γυναῖκες.

τῶν μὲν πολλῶν θοῦρος Ἄρης ὑπὸ γούνατ’ ἔλυσεν:

ὃς δέ μοι οἶος ἔην, εἴρυτο δὲ ἄστυ καὶ αὐτούς,

τὸν σὺ πρῴην κτεῖνας ἀμυνόμενον περὶ πάτρης

Ἕκτορα: τοῦ νῦν εἵνεχ’ ἱκάνω νῆας Ἀχαιῶν

λυσόμενος παρὰ σεῖο, φέρω δ’ ἀπερείσι’ ἄποινα.

ἀλλ’ αἰδεῖο θεοὺς Ἀχιλεῦ, αὐτόν τ’ ἐλέησον

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός: ἐγὼ δ’ ἐλεεινότερός περ,

ἔτλην δ’ οἷ’ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθόνιος βροτὸς ἄλλος,

ἀνδρὸς παιδοφόνοιο ποτὶ στόμα χεῖρ’ ὀρέγεσθαι.

ὣς φάτο, τῷ δ’ ἄρα πατρὸς ὑφ’ ἵμερον ὦρσε γόοιο:

ἁψάμενος δ’ ἄρα χειρὸς ἀπώσατο ἦκα γέροντα.

τὼ δὲ μνησαμένω ὃ μὲν Ἕκτορος ἀνδροφόνοιο

κλαῖ’ ἁδινὰ προπάροιθε ποδῶν Ἀχιλῆος ἐλυσθείς,

αὐτὰρ Ἀχιλλεὺς κλαῖεν ἑὸν πατέρ’, ἄλλοτε δ’ αὖτε

Πάτροκλον: τῶν δὲ στοναχὴ κατὰ δώματ’ ὀρώρει.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεί ῥα γόοιο τετάρπετο δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς,

καί οἱ ἀπὸ πραπίδων ἦλθ’ ἵμερος ἠδ’ ἀπὸ γυίων,

αὐτίκ’ ἀπὸ θρόνου ὦρτο, γέροντα δὲ χειρὸς ἀνίστη

οἰκτίρων πολιόν τε κάρη πολιόν τε γένειον.

Image: Bertel Thorvaldsen, “Priam Pleads with Achilles for Hector’s Body,” 1868-1870.

O Swineherd, Where Art Thou? (Odyssey 14.48-61)

May 1, 2013

Nick Stender examines the scene in the Odyssey where Odysseus, dressed as a beggar, shows up at the hut of the swineherd Eumaeus, and is received with gallant swineherd hospitality–quite a contrast to the supposedly noble suitors who are occupying Odysseus’ palace. What does this scene reveal about the custom of xenia or guest-friendship in dark age Greece? Odyssey 14.48-61, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Nick Stender.

Odysseus and Eumaeus

ὣς εἰπὼν κλισίηνδ’ ἡγήσατο δῖος ὑφορβός,

εἷσεν δ’ εἰσαγαγών, ῥῶπας δ’ ὑπέχευε δασείας,

ἐστόρεσεν δ’ ἐπὶ δέρμα ἰονθάδος ἀγρίου αἰγός,

αὐτοῦ ἐνεύναιον, μέγα καὶ δασύ. χαῖρε δ’ Ὀδυσσεύς,

ὅττι μιν ὣς ὑπέδεκτο, ἔπος τ’ ἔφατ’ ἔκ τ’ ὀνόμαζε·

“Ζεύς τοι δοίη, ξεῖνε, καὶ ἀθάνατοι θεοὶ ἄλλοι,

ὅττι μάλιστ’ ἐθέλεις, ὅτι με πρόφρων ὑπέδεξο.”

τὸν δ’ ἀπαμειβόμενος προσέφης, Εὔμαιε συβῶτα·

“ξεῖν’, οὔ μοι θέμις ἔστ’, οὐδ’ εἰ κακίων σέθεν ἔλθοι,

ξεῖνον ἀτιμῆσαι· πρὸς γὰρ Διός εἰσιν ἅπαντες

ξεῖνοί τε πτωχοί τε. δόσις δ’ ὀλίγη τε φίλη τε

γίνεται ἡμετέρη· ἡ γὰρ δμώων δίκη ἐστίν,

αἰεὶ δειδιότων, ὅτ’ ἐπικρατέωσιν ἄνακτες

οἱ νέοι.

Homer’s Divine Inspiration (Odyssey 8.487-498)

May 1, 2013

Solai Sanchez explores the Greek idea of poetry as divinely inspired, and poets as bestowers of immortality. In Book 8 of the Odyssey Odysseus praises the poet Demodocus by saying that he must have learned his craft from the Muse, or from Apollo. What does this mean, exactly? Odyssey 8.487-498 discussed, translated, and read aloud by Solai Sanchez.

“Δημόδοκ’, ἔξοχα δή σε βροτῶν αἰνίζομ’ ἁπάντων·

ἢ σέ γε Μοῦσ’ ἐδίδαξε, Διὸς πάϊς, ἢ σέ γ’ Ἀπόλλων·

λίην γὰρ κατὰ κόσμον Ἀχαιῶν οἶτον ἀείδεις,

ὅσσ’ ἕρξαν τ’ ἔπαθόν τε καὶ ὅσσ’ ἐμόγησαν Ἀχαιοί,

ὥς τέ που ἢ αὐτὸς παρεὼν ἢ ἄλλου ἀκούσας.

ἀλλ’ ἄγε δὴ μετάβηθι καὶ ἵππου κόσμον ἄεισον

δουρατέου, τὸν Ἐπειὸς ἐποίησεν σὺν Ἀθήνῃ,

ὅν ποτ’ ἐς ἀκρόπολιν δόλον ἤγαγε δῖος Ὀδυσσεὺς

ἀνδρῶν ἐμπλήσας, οἳ Ἴλιον ἐξαλάπαξαν.

αἴ κεν δή μοι ταῦτα κατὰ μοῖραν καταλέξῃς,

αὐτίκα καὶ πᾶσιν μυθήσομαι ἀνθρώποισιν,

ὡς ἄρα τοι πρόφρων θεὸς ὤπασε θέσπιν ἀοιδήν.”

Divine License (Iliad 21.342-355)

May 1, 2013

Morisseau_podcast_Greek112_2013

Will Morriseau argues that uses the gods to impose his own will on the poem. His freedom with the facts is “divine license,” and Homer himself is the only real deity in the work. Will discusses this idea in the context of a puzzling simile in Iliad 21, where Hephaestus is scorching the battlefield. Iliad 21.342-355, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Will Morriseau.

Ὣς ἔφαθ’, Ἥφαιστος δὲ τιτύσκετο θεσπιδαὲς πῦρ.

πρῶτα μὲν ἐν πεδίῳ πῦρ δαίετο, καῖε δὲ νεκροὺς

πολλούς, οἵ ῥα κατ’ αὐτὸν ἅλις ἔσαν, οὓς κτάν’ Ἀχιλλεύς·

πᾶν δ’ ἐξηράνθη πεδίον, σχέτο δ’ ἀγλαὸν ὕδωρ.

ὡς δ’ ὅτ’ ὀπωρινὸς Βορέης νεοαρδέ’ ἀλωὴν

αἶψ’ ἀγξηράνῃ· χαίρει δέ μιν ὅς τις ἐθείρῃ·

ὣς ἐξηράνθη πεδίον πᾶν, κὰδ δ’ ἄρα νεκροὺς

κῆεν· ὃ δ’ ἐς ποταμὸν τρέψε φλόγα παμφανόωσαν.

καίοντο πτελέαι τε καὶ ἰτέαι ἠδὲ μυρῖκαι,

καίετο δὲ λωτός τε ἰδὲ θρύον ἠδὲ κύπειρον,

τὰ περὶ καλὰ ῥέεθρα ἅλις ποταμοῖο πεφύκει·

τείροντ’ ἐγχέλυές τε καὶ ἰχθύες οἳ κατὰ δίνας,

οἳ κατὰ καλὰ ῥέεθρα κυβίστων ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα

πνοιῇ τειρόμενοι πολυμήτιος Ἡφαίστοιο.

A Hero’s Best Friend (Odyssey 17.290-304)

May 1, 2013

The famous scene in which Argus, Odysseus’ faithful dog, recognizes Odysseus on his return and promptly expires, is more than just pathos, argues Lucy McInerney. It is also an opportunity for Homer to show the fortitude of Odysseus himself. In other recognition scenes, she points out, Odysseus is able to share his emotions with whoever it is that recognizes him. In the case of Argus, the only character in the whole epic to recognize Odysseus on sight, he has to turn away and pretend not to know him. Odyssey 17.290-304 discussed, translated, and read aloud by Lucy McInerney.

John Flaxman, Odysseus and Argos (1805) Engraving and etching on paper, Tate Gallery

ὣς οἱ μὲν τοιαῦτα πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἀγόρευον·

ἂν δὲ κύων κεφαλήν τε καὶ οὔατα κείμενος ἔσχεν,

Ἄργος, Ὀδυσσῆος ταλασίφρονος, ὅν ῥά ποτ’ αὐτὸς

θρέψε μέν, οὐδ’ ἀπόνητο, πάρος δ’ εἰς Ἴλιον ἱρὴν

ᾤχετο. τὸν δὲ πάροιθεν ἀγίνεσκον νέοι ἄνδρες

αἶγας ἐπ’ ἀγροτέρας ἠδὲ πρόκας ἠδὲ λαγωούς·

δὴ τότε κεῖτ’ ἀπόθεστος ἀποιχομένοιο ἄνακτος

ἐν πολλῇ κόπρῳ, ἥ οἱ προπάροιθε θυράων @1

ἡμιόνων τε βοῶν τε ἅλις κέχυτ’, ὄφρ’ ἂν ἄγοιεν

δμῶες Ὀδυσσῆος τέμενος μέγα κοπρίσσοντες·

ἔνθα κύων κεῖτ’ Ἄργος ἐνίπλειος κυνοραιστέων.

δὴ τότε γ’, ὡς ἐνόησεν Ὀδυσσέα ἐγγὺς ἐόντα,

οὐρῇ μέν ῥ’ ὅ γ’ ἔσηνε καὶ οὔατα κάββαλεν ἄμφω,

ἄσσον δ’ οὐκέτ’ ἔπειτα δυνήσατο οἷο ἄνακτος

ἐλθέμεν· αὐτὰρ ὁ νόσφιν ἰδὼν ἀπομόρξατο δάκρυ,

ῥεῖα λαθὼν Εὔμαιον, ἄφαρ δ’ ἐρεείνετο μύθῳ·

Women are not to be trusted, says the ghost of Agamemnon to Odysseus in the underworld in Book 11 of the Odyssey. Penelope is an exception, even he admits, while advising caution to Odysseus on his return home. Allison Hummel argues that this passage praising Penelope in the middle of the Odyssey is crucial to reminding Odysseus, and us, about the meaning of Odysseus’ great struggle to get home. Homer, Odyssey 11.440-456, discussed, translated, and read aloud by Allison Hummel.

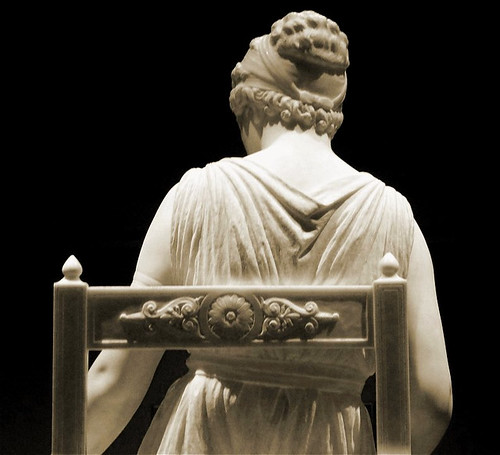

Penelope. Detail of the statue by American sculptor Franklin Simmons

ὣς ἐφάμην, ὁ δέ μ᾽ αὐτίκ᾽ ἀμειβόμενος προσέειπε:

‘τῷ νῦν μή ποτε καὶ σὺ γυναικί περ ἤπιος εἶναι:

μή οἱ μῦθον ἅπαντα πιφαυσκέμεν, ὅν κ᾽ ἐὺ εἰδῇς,

ἀλλὰ τὸ μὲν φάσθαι, τὸ δὲ καὶ κεκρυμμένον εἶναι.

ἀλλ᾽ οὐ σοί γ᾽, Ὀδυσεῦ, φόνος ἔσσεται ἔκ γε γυναικός:

λίην γὰρ πινυτή τε καὶ εὖ φρεσὶ μήδεα οἶδε

κούρη Ἰκαρίοιο, περίφρων Πηνελόπεια.

ἦ μέν μιν νύμφην γε νέην κατελείπομεν ἡμεῖς

ἐρχόμενοι πόλεμόνδε: πάϊς δέ οἱ ἦν ἐπὶ μαζῷ

νήπιος, ὅς που νῦν γε μετ᾽ ἀνδρῶν ἵζει ἀριθμῷ,

ὄλβιος: ἦ γὰρ τόν γε πατὴρ φίλος ὄψεται ἐλθών,

καὶ κεῖνος πατέρα προσπτύξεται, ἣ θέμις ἐστίν.

ἡ δ᾽ ἐμὴ οὐδέ περ υἷος ἐνιπλησθῆναι ἄκοιτις

ὀφθαλμοῖσιν ἔασε: πάρος δέ με πέφνε καὶ αὐτόν.

ἄλλο δέ τοι ἐρέω, σὺ δ᾽ ἐνὶ φρεσὶ βάλλεο σῇσιν:

κρύβδην, μηδ᾽ ἀναφανδά, φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν

νῆα κατισχέμεναι: ἐπεὶ οὐκέτι πιστὰ γυναιξίν.

The bringer of dark pains (Iliad 4.105-126)

May 16, 2012

Homer describes the deadly goat-horn bow of Pandarus. What kind of bow was it, and how does it relate to bows known from the Bronze Age Mediterranean? Iliad 4.105-126, read, translated, and discussed by Jimmy Martin.

αὐτίκ’ ἐσύλα τόξον ἐΰξοον ἰξάλου αἰγὸς (105)

ἀγρίου, ὅν ῥά ποτ’ αὐτὸς ὑπὸ στέρνοιο τυχήσας

πέτρης ἐκβαίνοντα δεδεγμένος ἐν προδοκῇσι

βεβλήκει πρὸς στῆθος· ὃ δ’ ὕπτιος ἔμπεσε πέτρῃ.

τοῦ κέρα ἐκ κεφαλῆς ἑκκαιδεκάδωρα πεφύκει·

καὶ τὰ μὲν ἀσκήσας κεραοξόος ἤραρε τέκτων, (110)

πᾶν δ’ εὖ λειήνας χρυσέην ἐπέθηκε κορώνην.

καὶ τὸ μὲν εὖ κατέθηκε τανυσσάμενος ποτὶ γαίῃ

ἀγκλίνας· πρόσθεν δὲ σάκεα σχέθον ἐσθλοὶ ἑταῖροι

μὴ πρὶν ἀναΐξειαν ἀρήϊοι υἷες Ἀχαιῶν

πρὶν βλῆσθαι Μενέλαον ἀρήϊον Ἀτρέος υἱόν. (115)

αὐτὰρ ὁ σύλα πῶμα φαρέτρης, ἐκ δ’ ἕλετ’ ἰὸν

ἀβλῆτα πτερόεντα μελαινέων ἕρμ’ ὀδυνάων·

αἶψα δ’ ἐπὶ νευρῇ κατεκόσμει πικρὸν ὀϊστόν,

εὔχετο δ’ Ἀπόλλωνι Λυκηγενέϊ κλυτοτόξῳ

ἀρνῶν πρωτογόνων ῥέξειν κλειτὴν ἑκατόμβην

οἴκαδε νοστήσας ἱερῆς εἰς ἄστυ Ζελείης.

ἕλκε δ’ ὁμοῦ γλυφίδας τε λαβὼν καὶ νεῦρα βόεια·

νευρὴν μὲν μαζῷ πέλασεν, τόξῳ δὲ σίδηρον.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ κυκλοτερὲς μέγα τόξον ἔτεινε,

λίγξε βιός, νευρὴ δὲ μέγ’ ἴαχεν, ἆλτο δ’ ὀϊστὸς (125)

ὀξυβελὴς καθ’ ὅμιλον ἐπιπτέσθαι μενεαίνων

The funeral pyre of Patroclus

May 15, 2012

The funeral pyre of Patroclus, discussed in the context of Homeric, Mycenaean, and Protogeometric burial customs, by Andrew Shoemaker, followed by his reading and translation of the relevant passage of the Iliad.

The shield of Ajax (Iliad 7.211-223)

May 15, 2012

Shields in Homer and in bronze age art, discussed by Marjorie Haines. There follows a reading of Iliad 7.211-223, which describes Ajax’s “tower” shield (first in Greek, then in her English translation).

τοῖος ἄρ’ Αἴας ὦρτο πελώριος ἕρκος Ἀχαιῶνμειδιόων βλοσυροῖσι προσώπασι· νέρθε δὲ ποσσὶνἤϊε μακρὰ βιβάς, κραδάων δολιχόσκιον ἔγχος.τὸν δὲ καὶ Ἀργεῖοι μὲν ἐγήθεον εἰσορόωντες,Τρῶας δὲ τρόμος αἰνὸς ὑπήλυθε γυῖα ἕκαστον, (215)Ἕκτορί τ’ αὐτῷ θυμὸς ἐνὶ στήθεσσι πάτασσεν·ἀλλ’ οὔ πως ἔτι εἶχεν ὑποτρέσαι οὐδ’ ἀναδῦναιἂψ λαῶν ἐς ὅμιλον, ἐπεὶ προκαλέσσατο χάρμῃ.Αἴας δ’ ἐγγύθεν ἦλθε φέρων σάκος ἠΰτε πύργονχάλκεον ἑπταβόειον, ὅ οἱ Τυχίος κάμε τεύχων (220)σκυτοτόμων ὄχ’ ἄριστος Ὕλῃ ἔνι οἰκία ναίων,ὅς οἱ ἐποίησεν σάκος αἰόλον ἑπταβόειονταύρων ζατρεφέων, ἐπὶ δ’ ὄγδοον ἤλασε χαλκόν.τὸ πρόσθε στέρνοιο φέρων Τελαμώνιος Αἴαςστῆ ῥα μάλ’ Ἕκτορος ἐγγύς, ἀπειλήσας δὲ προσηύδα· (225)Ἕκτορ νῦν μὲν δὴ σάφα εἴσεαι οἰόθεν οἶος