Annaliese Tucci

Introduction

My final project explores the following question: to what extent did fascist initiatives influenced Argentine society during the twentieth century. The spread of fascism in South America was not the direct result of the policies of the Italian government and Benito Mussolini, but there is a great influence that cannot be ignored. My objective is not to blame Italy for the presence of fascism in Argentina (because there are many different reasons) but to research the connection between the two countries and explore the impact of Italian policies during the Mussolini period and also after the second world War. I concentrate on the opportunities and programs for Italians in Argentina to remain devoted to the Italian homeland during the rise of fascism.

I also explore how such programs have influenced the Argentine government as of Juan Perón and finally, I concentrate on the wave of emigration after World War II, specifically, the fascists who sought to escape from Europe after the war. While fascists and propaganda programs spread throughout all of Argentina in the’ 20s and ’30s, they never transformed Argentine society as the Italian government had hoped for. In the midst of fascist propaganda, there was always anti-fascist propaganda and while many remained devoted to the homeland, many others did not have such loyalty. There was a wave of fascist emigration to Argentina but there was also a wave of refugees fleeing fascism in Italy. This project focuses on the influence of fascist projects in Argentina, but resistance to the existence of fascism was a powerful component and should not be discredited.

fascist interests in argentina

Fascism was a political movement, born in northern Italy in the early twentieth century. Fascism has never been concrete, but has always been reactive towards other ideologies (Finchelstein,17). While there was never a completely fascist regime in Argentina, the influence of Italian policies and politics in Argentina was unique. There were Argentine politicians that supported Mussolini’s government and so, “like the Argentine state, Argentine society Remained extremely receptive to fascism between the years of 1919 and 1945” (Finchelstein , 57). The fundamental reason for Italian interests towards Argentina was a result of the wave of Italian immigrants in Argentina, the most significant group in the whole of Argentina. While Mussolini was against Italian emigration, “If emigration could not be avoid, Italian emigration, he argued should be seen as an act of expansion” (Finchelstein, 38).

Group of Italian immigrants at Immigrants Hotel in Buenos Aires

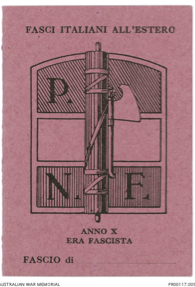

Through I Fasci Italiani all’Estero [Italian Fascists Abroad], the different programs for Italian youth and adults, as well as the education reform for Italian schools abroad, Mussolini obtained the support of many Italian immigrants. At the same time, many immigrants to South America left Italy to escape fascism, and thus, there were also many anti-fascist movements during the same period. For example, Severino Di Giovanni was one of the most famous anti-fascist Italians in Argentina during the twentieth century and was active in the movement anti-fascists in the 20s. He was part of the anarchist movement and took part in violent riots against fascism. Di Giovanni was executed in February 1931 and his last words before receiving eight bullets were: “Lunga vita all’anarchia!” or “Long Live Anarchy” (O’Higgins). The history of Saverino is complex but he is an example of the anti-fascist extremists present in Buenos Aires.

ITALIAN FASCIST PROGRAMS IN ARGENTINA FROM 1920-1930

The wave of fascism in Italy during the 1920s arrived in Argentina with the formation of the various fascist programs for Italians abroad. The loyalty and support of Italian immigrants abroad was fundamental for the survival and spread of fascism. There was a valorization of the immigrant communities abroad to create an Italian identity abroad. For Mussolini, fascism was fundamentally linked to Italian national identity and thus, to be Italian meant to obey and respect Mussolini’s policies.

Valorization meant reclaiming the emigrant for the patria by providing the Italian abroad an important role to play in the New Italy.”

– David Aliano

(Mussolini’s National Project in Argentina, p.30)

As a result of this policy agenda, Mussolini created the Fasci Italiani all’Estero [Italian Fascists Abroad] in 1923 and restructured the Italian school system in Argentina and around the world (Aliano, 32). By 1925, the Dopolavoro all’Estero [Dopolavoro Abroad] was created for Italian adults. Programs and activities were created to instill love for the homeland. From 1927 to 1936, there was a high level of fascist interest in South America (Aliano, 58). One reason why Argentina was so attractive is because: “By the time the fascists came to power in Italy in 1922, Italian immigrants had firmly established themselves within Argentina’s socioeconomic landscape ” (Aliano, 55). After the unification of Italy, there was a wave of emigration to Argentina and therefore, a foundation in Argentina was the best option for the fascists. Despite the efforts, according to Federica Bertagna in La Stampa italiana in Argentina: “i numeri degli iscritti al Fascio e alle sezioni del Dopolavoro a Buenos Aires sono eloquenti: in una collettività che alla fine de

A membership card of Italian Fascists Abroad (Australian War Memorial)

gli anni trenta raggiungeva le 300.000 persone, i primi non superarono mai i 4000” (148). While the influence of fascism was always present in Argentina, it never became the powerful tool that Mussolini and the Italian government had hoped for.

In 1928, Mussolini ordered the organization of Italian youth programs abroad and began to pay particular attention to Italian youth programs. There was a problem of how to “fascistizzare” Italian society and the control of Italian youth was a fundamental tactic. The creation of the Opera Nazionale Balilla [National Balilla Opera] in Argentina was fundamental for the fascist government to attract Italian youth. In 1933, there was the first fascist summer camp in Argentina and throughout South America. In the months of January and February, a hundred children of Italian origins participated in the camp (Aliano, 72). In 1935 there were 3 operating camps throughout Argentina and eventually also developed in Uruguay and Brazil. While the creation of a summer camp may not seem extraordinary, the influence of the summer camp had the potential to change the mentality of youth, towards loyalty to fascism, the homeland, and Benito Mussolini.

This nationalization project was prevalent in literature, textbooks, and in the curriculum of Scuole Italiane all’Estero [Italian Schools Abroad]. According to Aliano, “these books attempted to nationalize the children of Italian immigrants in Argentina, reincorporating them into the Italian nation by

Mussolini with a Balilla

instilling in them values and ideals of the New Italy” (Aliano, 109). While fascist programs gained popularity, they never became what was hoped for. One of the reasons is due to the Italian embassy’s position on the Italian schools that had “propagated the cult of Il Duce and the new Italian empire” (Newton, 191). In 1938, the Italian Ambassador Raffaele Guariglia announced that the Italian government would not continue its project to build a scholastic structure model in Buenos Aires and in 1939, the Italian foreign ministers threatened to close all Italian schools in Argentina (Newton, 191). Despite disagreements with the Italian government and the Argentine government, “the Italian schools retained the symbols and paraphernalia of fascist Italy ” (Newton, 205). This confrontation demonstrated that the Italian government did not had enough influence to transform the entire Argentine educational system.

The reason for programs abroad is simple: the valorization of Italian emigrant communities as an effort to promote fascist ideology all over the world. The homeland is where the hearts of the people are located and the countries of emigration were useful only to promote the expansion and glory of Italy.

fascist propaganda in argentina from 1920-1930

Partito Nazionale Fascista. Mostra nazionale delle colonie estive e dell’assistenza all’infanzia, 1937

The influence of Italian fascism in Argentina also extends to the diffusion of propaganda, mainly through the press. By 1923, fascist propaganda reached Argentina, through the delegate of the Italian Fascist National Party for South America, Ottavio Dinale . Dinale convinced Mussolini to finance a fascist newspaper for Argentina, Il Littore , which began publishing in Buenos Aires in October 1923 (Newton, 46). In 1930, Vittorio Valdini , the main financier of the operation and the leader of the fascists in Argentina, founded a new fascist newspaper, Il Mattino d’Italia, based in Buenos Aires (Newton, 57). As fascism grew, its propaganda also grew.

Above all , Il Mattino d’Italia was a fundamental tool of fascist propaganda. According to Bertagna , the initial edition of Il Mattino d’Italia consisted of around 10,000 copies (63). During the conflict in Ethiopia between 1935 and 1936, the newspaper reached approximately 40,000 copies (63). The main objective of the fascist press was to “conquistare un ampio consenso tra la massa degli emigrati” (Bertagna, 60).

In Argentina, e altrove, l’apertura di sezioni dei Fasci nella prima metà degli anni venti era state seguita dalla pubblicazione di vari periodici di ispirazione fascista, tra cui il settimanale Il Littore (1923), il mensile Terra d’oltremare (1925) e il Risveglio (1927) a Buenos Aires; Disciplina (1926) a Rosario e Italicus (1927) a Bahía Blanca.”

– Federica Bertagna

(La Stampa Italiana in Argentina, p.60)

Il Mattino d’Italia “The Duce acclaimed at the Mussolini Forum by thousands of young people who have come from all over Italy and from abroad” (August 6,1937)

There was also a significant number of anti-fascist publications. One of these , La Nuova Patria, was a newspaper with a democratic orientation in Argentina (Bertagna , 65). One of the most famous anti-fascist magazines was L’Italia del popolo. As Federica Bertagna observes in her book, La Stampa Italiana in Argentina: “è indubbio che essa funge da catalizzatore di tutte le iniziatie degli antifascisti, dalle denunce sull’infiltrazione di elementi fascisti ai vertici delle associazioni della collettività, alle raccolte di fondi in favore dei perseguitati e degli esuli” (117). For antifascists in Argentina, L’Italia del popolo was the most popular anti-fascist paper. The history of fascist and anti-fascist propaganda in Argentina is extensive, but it is safe to say that where fascists existed abroad, there were also many antifascists who opposed Mussolini. The power of the press helped to push both fascist and anti-fascist agendas throughout all of Argentina.

italian emigration after world war ii and the protection of fascists in argentina

Colonialism as an alternative to emigration

In early 1922, the Italian government discouraged emigration to Argentina but despite these efforts from 1919 to 1925, approximately 372,000 Italians emigrated to Argentina. However, in 1926 the numbers began to decrease drastically and between 1926 and 1940 only 80.3 thousand Italians immigrated (Newton, 45). The new Italy rejected emigration as an act of treason to the homeland. The press represented images of colonialism as an alternative to emigration. If emigration was prohibited, the expansion of Italy into Africa would become a good alternative.

In September 1927, the government created a new emigration policy in which migration abroad was prohibited to Italian citizens (Newton, 52). Despite the stop of immigration, the fascist agenda in Argentina continued with the formation of programs such as the Dopolavoro, the Patronato del Lavoro, Balilla (Gioventù Italiana Littorio nell’Estero) and the control of some Italian schools (Newton, 55).

European Immigration to Argentina by Country of Origin. Ricardo Feierstein, Historia de los judíos argentinos (Buenos Aires: Editorial Planeta Argentina SAIC, 1993)

While in the 1920s and 1930s there were Italian fascist programs in Argentina, in the 1940s, there was a new wave of Italian emigration to Argentina. After 1945, Argentina prepared for the emigration of fascist refugees from Italy. There was a wave of emigration after the Second World War, both refugees fleeing fascism and fascists wishing to escape post-war Europe. In the article, “L’emigrazione fascista e neofascista nel secondo dopoguerra (1945-1985)”, Federica Bertagna describes the barrier between the criminals who escaped Italy and those who went abroad to find work after the Second World War, and it is important to note that there were political and economic reasons behind migration around the world (2).

As Federica Bertagna writes in the article “Vinti o emigranti? Le memorie dei fascisti italiani in Argentina e Brasile nel secondo dopoguerra”, “alla conclusione della seconda guerra mondiale, la caduta del fascismo spinse molti degli sconfitti a lasciare l’Italia, definitivamente o in attesa di tempi migliori” (282). During this wave of emigration, many innocent people also left Italy in the hope of a better life. The fascists favored countries with a favorable economy and a secure political climate, such as Peronist Argentina and Brazil ( Bertagna , 283). In this sense , the climate policy ” safe ” in Brazil and Argentina was favorable and neutral in respect of the fascists , a difference of the United States of America , which to a certain point they fought the fascists during the war . Above all, “the decision to emigrate to Argentina stemmed from a sum of factors: the fear, above all, of arrest and conviction” ( Bertagna , 74).

Il passaporto falso di Adolf Eichmann (NBC News)

For many fascists, Argentina was a safe haven: the Argentine government under Perón provided refuge, Vittorio Valdini , who was an Italian entrepreneur and the leader of the fascist movement in Argentina, still supported fascist initiatives and the Italian government, the Vatican and the Red Cross distributed false passports to former Nazis and fascists (Bertagna , 286). There are many reasons for the actions of the Vatican and the Red Cross, but the most interesting thing is the fear of communism that is spreading in these countries . According to the work of intelligence, “i fascisti entravano in possesso di falsi passaporti attraverso le strutture di assistenza ai profughi, con un metodo identico a quello che consentiva ai criminali di Guerra nazisti e ai collaborazionisti di lasciare l’Europa” (Bertagna, 63). The most notable escape Nazi was the escape of Adolf Eichmann to Argentina in 1950. He fled with his family under a false passport , issued by the delegation of Italian of the Red Cross. Under the false name of “Riccardo Klement “, Eichmann fled Europe from the port of Genoa in Italy and for some time took refuge in Argentina before being captured and sent to Israel .

During Juan Perón ‘s rule, the Argentine government supported and protected war criminals from World War II, fascists and nazis. Perón secretly ordered diplomats to create escape routes, also known as “ratlines”, through ports in Spain and Italy, which would illegally bring over thousands of ex-SS officers and members of the Nazi / Fascist party from Europe. Argentina was in fact ““l’unico stato che accettava i passaporti per apolidi della Croce rossa internazionale, gli unici che costoro potevano procurarsi” (Bertagna, 9).

Juan Perón

It is important to note that Peron publicly admired Mussolini. His support for Mussolini is well documented and during a trip to Europe in 1938 he stated:

“Italian Fascism made people’s organizations participate more on the country’s political stage. Before Mussolini’s rise to power, the state was separated from the workers, and the former had no involvement in the latter. […] Exactly the same process happened in Germany, that is the state was organized [to serve] for a perfectly structured community, for a perfectly structured population: a community where the state was the tool of the people, whose representation was, in my opinion, effective.”

– Juan Perón

While Peronism was not the same as Fascism, the influence of people like Benito Mussolini is evident. In fact, “the rise of Perón evoked recollections of events in Italy twenty years earlier . Peronist Youth – not to mention the thuggish Nationalists left over from the 1930s – were disquietingly reminiscent of the squadristi, and Perón himself – charismatic , bombastic , intelligent , affably macho-bore more than a passing resemblance to Il Duce “(Newton, 66) .

Juan Perón

While Peronism is its own movement, there is no doubt that Perón was influenced by Mussolini and other fascists. As Finchelstein writes in his book Translatlantic Fascism: Ideology , Violence , and the Sacred in Argentina and Italy 1919-1945 , fascism eventually became “transatlantic” and was formed in different ways by the fascist programs of the 20s and 30s. The influence of Italian fascism through outlets such as the press and programs in Argentina had an impact on Argentine society, so much so that the Argentine president protected the fascists fleeing Italy after the Second World War. While Argentina has never seen a fascist movement like Italy did under Mussolini, the influence of fascism during this period became even more evident through the policies under Perón .

Bibliography

Aliano, David. Mussolini’s National Project in Argentina Lanham, Maryland: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2012.

Bertagna, Federica. La stampa italiana in Argentina. Roma: Donzelli, 2009.

Bertagna, Federica. La patria di riserva: l’emigrazione fascista in Argentina. Roma: Donzelli, 2006.

Bertagna, Federica. “L’emigrazione fascista e neofascista nel secondo dopoguerra (1945-1985)”. https://www.academia.edu/37568567/Lemigrazione_fascista_e_neofascista_nel_secondo_dopoguerra_1945-1985_

Bertagna, Federica. “Vinti o emigranti? Le memorie dei fascisti italiani in Argentina e Brasile nel secondo dopoguerra.” História: Debates e Tendências, vol.13, no. 2, 2013, pp. 282-294.

Finchelstein, Federico. Transatlantic Fascism : Ideology, Violence, and the Sacred in Argentina and Italy, 1919-1945 . Duke University Press, 2010.

O’Higgins, Sorcha. “Meet Severino Di Giovanni, Argentina’s Most Famous Italian Anarchist.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 3 May 2018, theculturetrip.com/south-america/argentina/articles/meet-severino-di-giovanni-argentinas-most-famous-italian-anarchist/.

Newton, Ronald C. The “Nazi Menace” in Argentina, 1931-1947 . Stanford University Press, 1992.

Newton, Ronald C. “Ducini, Prominenti, Antifascisti: Italian Fascism and the Italo-Argentine Collectivity, 1922-1945.” The Americas, vol. 51, no. 1, 1994, pp. 41–66. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1008355. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020.