Soccer, emigration and racism

by Odalis Almendarez Piña

Soccer is one of the best-known sports in the world, especially in Italy, which is view with great love. Soccer is known as a sport that unites everyone, not only the players but also the fans, regardless of age, race, gender, culture or nationality. This makes it a beautiful sport to play and watch. However, this has not always been the case. There were several rules that established who could play in the national teams, the acceptance of foreign players was very regulated, especially in Italy, where the game of soccer was tied for a long time to emigration, which brought millions of Italians to the countries of South America.

“The idea that politics and sport should be kept apart is laughable in Italy.” (Foot, 355)

Mussolini and Italian Team, World Cup 1934

There was an intertwining of soccer and politics that shaped soccer in Italy. In the 1920s in Italy the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini was starting which helped continued the rise of nationalism that Enrico Corradini has started around

1910s. This intertwining was between soccer, emigration and the political rise during fascism. Now, if we look back in history, we are able to see how the fascist movement used soccer to implement its ideals. Both, soccer and fascism, promoted the collectivity rather than just a single person, that is, the team or the country over individuals ( Emma, Almog , and Taylor). This was what Mussolini understood, and therefore he used soccer for his benefit (Noonan).

Mussolini’s fascist party began to shape the sport, creating the Carta di Viareggio in 1926. The Carta di Viareggio prohibited having more than two foreign players on the team until 1928, when it the changed to banning any foreign player in the Italian team (Foot, 38). In addition to that, La Carta di Viareggio officially recognized soccer as a profession for the first time (Foot, 25). At the start of soccer in Italy, soccer was an amateur sport which was only played for honor and entertainment, never for money. Players at this time had their own profession while they played, over time this had to changed (Foot 38). In 1920, this system was no longer working, and money had begun to flow. These transfers of money led to a bitter public discussion that contributed also to the creation of the Carta di Viareggio (Viareggio Charter) (Foot, 24).

However, this new set of rules contained a loophole. The Viareggio Charter only stated that foreigners were prohibited, which rose a lot of questions. Such as who was considered an Italian? Who was considered a foreigner? Many of the foreign players Italy had were from Hungary and Austria which could no longer play, therefore Italian clubs began to look for other players who were ‘Italian’ (Foot, 38). They were turning to look for Italians who have emigrated from the country in the past. This great emigration of Italians is known as the Italian diaspora.

“South Americans as Italians … Italians as South Americans” (Foot, 391)

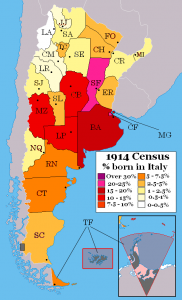

Because of this diaspora there are large groups concentrated Italian communities in South America, especially in Argentina and Brazil. It is estimated that the numbers of their “Italian oriundi” descendants are very high, Argentina had received almost 3 million Italians (The Italian Diaspora).

Diaspora Italiana in Argentina

The ‘La Boca’ neighborhood is located near the shore of Buenos Aires in Argentina. La Boca is one of the districts that has a considerable concentration of an Italian community, it has registered 53% of its inhabitants to be Italian, especially from Genoa. At the center of La Boca is the La Bombonera stadium. This stadium is home to the Boca Juniors team, which was founded in 1905 by five Italian immigrants (Moralis).

La Boca is an Italian neighborhood, with its roots tied to the first emigration from Italy. With the Italian diaspora, soccer spread throughout South America, and players born in Argentina formed the majority of foreigners who played in Italy in the 1920s (Moralis). Throughout the years, Boca Juniors has helped create great soccer players that have left to play in Italy (Foot, 392).

The presence of foreign players in Italian soccer has always been the subject of a debate that have influenced the changing rules that governed the game. After La Carta di Viareggio, only the oriundi were allowed to play. At this time, it was when the Italian oriundo category became part of soccer.

Oriundo is an Italian word that comes from the Spanish language which means “originating from” (Bonello). Although these players were not natives Italians, they qualify to play for the country if they meet certain criteria. These players had to have a close ancestral link with the ‘ Italy (Foot, 392)

These players had Italian ‘blood’, Italian surnames, and Italian parents, but often they had never been to Italy, and they didn’t speak Italian (Noonan).

La Bombonera, Buenos Aires

Although they were not born in Italy, due to this new set of rules, these players could play in Italy. The Viareggio Charter was in place until 1949, but after six years in 1955, the “oriundi’ were able back national (Foot,392).

These South American players were going to Italy to play because it was good money. At the end of the 1920s Italian soccer was very wealthy, therefore being able to buy these start players from Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. During this time the South American soccer was not wealthy like Italy, which made it difficult to compete against it to keep their players. The lost of these players seemed like a form of neo-colonialism (Foot, 393). Argentina was in an economic crisis and therefore losing these inevitable players.

Oriundi footballers: From Argentina to Italy

Julio Libonatti

One of the best known players as an oriundo was Julio Libonatti , called “El Matador” for his talent for the ball. He was born in Rosario in Argentina to a Calabrian family. Therefore, he had the opportunity to be part of this ‘oriundi’phenomenon. Libonatti played first with the Argentine national team from 1919 to 1922. After four years, from 1926 to 1931, Libonatti played for the national team of Italy. His matches attracted people from all over the country and even from abroad. Thanks to his talent, one of these people who looked at him was Count Enrico Marone Cinzano, the president of Turin (Castellani). In his visit to Rosario, Cinzano had noticed that Libonatti had everything it takes to make an attacker shine: speed, agility, good movement of the ball with both feet, as well as a powerful and precise shot (Castellani). With all this and the fact that he was of Italian origin, Cinzano was more interested in having Libonatti in Italy. In 1925, Libonatti was registered for the transatlantic transfer, and later moved to the Italian club Torino (Pink). Libonatti had accepted because he liked new adventures, he become history because he was the first Argentine citizen to make the transatlantic transfer (Pink). Wherever he played he made history and this was not an exception to the Azzurri , the Italian national team. Libonatti played his first game for Italy in 1926, becoming the first oriundi to play in the Azzurri (Pink).

Julio Libonatti and Team

Because of Benito Mussolini’s Viareggio Charter, Libonatti was automatically given the dual nationality. This was accepted by the dictator Mussolini, because it was useful for Italy to give this oriundi their citizenship. Especially because thanks to oriundi, Italy was able to win the first World Cup in 1934.

Libonatti, after his 33 years, left the club of Torino, however he continued to play in different teams in the Serie B and Serie C (Pink). After living the dolce vita (the good life), he was bankrupt and then reunited with his family who was in Argentina after leaving Italy when the fascist regime started to suffocated Italy and was about to invade Albania. (Pink) Despite this, Julio Libonatti has opened the door for several changes in the future of soccer, especially because other oriundi had the opportunity to thrive in Italy over the years.

Benito Mussolini was not the first leader to recognize the political potential of sport, but he is one of the leaders who has placed the greatest emphasis on them (Bill, 65). For Benito Mussolini having that Italian team of 1934 where there were five oriundi – Atilio José Demaría, Raimundo Orsi, Luisito Monti, and Enrique Guaita who were Argentines and Anfilogino Guarisi who was Brazilian – was beneficial for Italy’s victory of the World Cup in 1934 (Deer). The victory helped Mussolini’s propaganda machine to represent the country as a symbol of fascist superiority in Europe.

The dirty-faced Angels

Humberto Maschio, Antonio Valentin Angelillo and Omar Sivori are three Argentine players who arrived in Italy towards the end of the 1950s (Foot, 397). The three of them were nicknamed “Dirty-faced angels”, like the title of a well-known 1940s movie starring Humprey Bogart and James Cagney. Having come to play in Europe the three players could no longer be called up by the Argentine national team, Albiceleste.

In the following years these “oriundi” had the opportunity to play for the Italian national team, the Azzurri, without luck to win a victory in the World Cup (Fossati).

Dirty-Faced Angels Maschio, Angelillo, Savori

But they became protagonists of the national championship becoming idols of the fans of their respective club teams Sivori and Maschio, together with other “oriundi” or naturalized, the Brazilians Josè Altafini and Angelo Sormani, participated in the disastrous expedition of the Italian national team to the World Championships in Chile in 1962 (Fossati).

In 1966, the Italian soccer borders closed for foreign players, this was because their presence was blamed for the continues low wins of the national team, especially after the humiliating defeat of North Korea at the World Cup in 1966.

In 1995, the so-called “Bosman ruling” established the free movement of workers / players within the European Community, without any restrictions (Foot, 502). “The numerical constraint survives – to date – for athletes from non-European countries” (Fossati). In this regulatory logic, the practice spread by agents and prosecutors of the search for European ancestry of non-EU footballers to facilitate their insertion in the “rich” European leagues, through the recognition of the double passport.

The return of the Oriundi to Italy

For almost two decades the Italian team had no oriundi in the Azzurri team, because Italian had this idea of detachment and of not belonging towards the oriundi. However, Mauro Camoranesi revived this tradition in 2003 (Lea). Mauro Camoranesi was born in Tandil, Argentina but was eligible for Italian citizenship thanks to his great-grandfather who had emigrated in 1873. He played for many club teams in Argentina, Mexico, Uruguay and Italy, but from 2003 to 2010 he represented Italy. The “Azzurri” had shown interest in him before the Argentina team, therefore Camoranesi made his international debut for Italy in a friendly match against the Portugal (Lea). When asked how he decided to represent the Azzurri (Italy) instead of the Albiceleste (Argentina) Camoranesi said that “Argentina never came looking for me, so I never had to choose. One day Trapattoni [soccer manager] called me. I thought his offer over and made up my mind almost two months ago to accept it. I remain an Argentinian, but this is a golden opportunity for my career “(Son of Argentina loyal to the Azzurri)

Mauro Camoranesi

In 2006, he won the World Cup in Germany with Italy; however, he was not fully accepted by his adopted country. There were a lot of critics against him, due to Italians not believe that he was worthy of wearing the blue jersey. For example, during the World Cup in 2006 he didn’t sing the Italian’s national anthem because he didn’t know it. He was also criticized for his interview after his victory in the World Cup when he said “me siento argentino pero he defendido los colores de Italia, que está en mi sangre, con dignidad. Eso es algo que nadie puede quitar” [he felt Argentinian but he defended the colors of Italy because it is his blood, with dignity, and nobody can take away that] but this was not enough for the Italians, especially because it was in Spanish (Casado).

“Nothing oriundi, only Italians in the national team” – Roberto Mancini

The concept of oriundi has created many questions about who a true Italian is. In the time of Mussolini’s dictatorship, it was useful to have oriundi players because they were star players who helped Italy win. At that time having a powerful team was also a symbol of a powerful nation.

Oriundi in Italian National Team

Although these players had Italian blood through their parents or grandparents, to what extent are they were truly Italian? Roberto Mancini is the coach of the Italian national team and former footballer of the Italian national team and other Italian clubs. He says that “niente oriundi, in Nazionale solo italiani…io penso che un giocatore italiano meriti di giocare in Nazionale, mentre chi non è nato in Italia, anche se ha dei parenti italiani, credo non lo meriti”[no oriundi, nella squadra nazionale… I think that an Italian player deserves to play in the national team, while those who were not born in Italy, even if they have Italian relatives, I think they don’t deserve it] (Zucchelli). Things like these are being listened a lot in soccer. These are the questions that Italians, and even Argentines ask themselves. Not only did Argentina lose its players to other nations, but Italy sometimes did not see these oriundi as true Italians.

The acceptance of Italian oriundi players has changed a lot throughout the time. The idea of the oriundi players at the start was in a sense as repatriation. During the fascist regime it was helpful to have these good players to have an invincible team. At one point these players were looked at as true Italians, but this didn’t last long. When the Azzurri won no there were not many critics contr or these natives, but when that does not happen there were many critics. With the change of Italian politics, the acceptance of foreigners and foreign players in the national team has also changed. The debate continues even now.

Top 11 Oriundi

The issue of acceptance is still ongoing in the world of football. A team composed only of the “Top” eleven oriundi would be similar to this image.The question in this team, if this team was possible, will ask who they are representing. Maybe a team representing immigrants? from the world? or a country? Would it be accepted? The constant question of who a true Italian is is, remains up to this date, not just in soccer. Is it enough to be an Italian descent? Does having an Italian passport make you Italian or is nothing enough? Even if were you born in Italy to immigrant parents, are you not Italian? Why is it easier for Italian child to obtain Italian citizenship, but not for those children born in Italy? To be a true Italian must you be born in an Italian family, in Italy and speak Italian? This debate will continue and will rise further questions about the true meaning of an Italian.

Bibliography

Emma Anspach , Hilah Almog , and Taylor (2009) “Football and Politics in Europe, 1930s-1950s”, Edited and Updated by Brittney Balser and Alessandro Santalbano (2013), Soccer Politics Pages, Soccer Politics Blog, Duke University, http: / /sites.duke.edu/wcwp

Bill Murray, The World’s Game: A History of Soccer . Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Bonello, Pierre. “Players: Oriundi “. Forza Azzurri Statistics. https://forza_azzurri.homestead.com/play_Oriundi.html

Casado, Edu. ” Qué fue de … Mauro Camoranesi : the Argentine que jugó por el país de su bisabuelo “. 20minutos. 23 Mar 2017. https://blogs.20minutos.es/quefuede/2017/03/23/que-fue-de-mauro-camoranesi-el-argentino-que-jugo-por-el-pais-de-su- Bisabuelo /

Castellani, Massimiliano. “Football & history . Libonatti , the Oriundo who opened the doors “. To come . Feb 13 2015. https://www.avvenire.it/agora/pagine/libonatti-

Deer, Gino. “Blue native – From Mumo Orsi in Palette : the naturalized at the World Cup .” Quasirete . Gazzeta of Sport. http://quasirete.gazzetta.it/2014/06/12/azzurro-oriundo-da-mumo-orsi-a-paletta-i-naturalizzati-ai-mondiali/

Foot, John. Winning at All Costs: A Scandalous History of Italian Soccer. Nation Books. 2006, 2007.

Fossati, Fulvio. 2020.

Lea, Greg. “Arrigo Sachi and Italian football’s ethical dilemma about foreign playrs “. The Guardian. Feb 18 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/football/these-football-times/2015/feb/18/arrigo-sacchi-italy-football-ethical-dilemma-racism-foreign-players

Moralis , Georgios. “Boca Juniors”. FootballHistory . https://www.footballhistory.org/club/boca-juniors.html

Noonan, Niall. “Mussolini’s World Cup”. Leftways . Medium. Nov. 12, 2017. https://medium.com/leftways/mussolinis-world-cup-445fb6606fc4

Pink. “Julio Libonatti : The First Trans-Atlantic Transfer.” The Football Pink. Nov. 21, 2018. https://footballpink.net/2018-11-16-julio-libonatti-the-first-trans-atlantic-transfer/

“Son of Argentina loyal to the Azzurri”. The Irish Times. Feb 11 2003. https://www.irishtimes.com/sport/son-of-argentina-loyal-to-the-azzurri-1.348504

“The Italian Diaspora”. PilotGuide . https://www.pilotguides.com/study-guides/the-italian-diaspora/

Zucchelli , Chiara. “Mancini:” Nothing oriundi , only Italians in the national team “. VOTE / You agree ? “. LaGazzettaDelloSport. 23 March , 2015. https://www.gazzetta.it/Calcio/Nazionale/23-03-2015/mancini-contro-oriundi-non-meritano-nazionale-solo-italiani-110209390555.shtml

Other readings

Acuña Gómez, Guillermo – Acuña Delgado, Ángel . “El fútbol como producto cultural: revisión y análisis bibliográfico ” in Citius , Altius, Fortius – 2016, 9 (2), pp. 31-58. Online: http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revcaf/Numeros%20de%20revista/Vol%209%20n2/Vol9_n2_Acunna_Acunna.pdf

Alabarces , Pablo (comp.). Futbologías : fútbol , identidad y violencia en América. Buenos Aires: Clacso , 2003.

Alabarces , Pablo. Fútbol y patria. Buenos Aires: Prometheus , 2007.

Clementi, Hebe, El protagonism of La Boca. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Letra Buena, 1994.

Lozato , Gianguglielmo . “Football and emigration : identity and identification . An analysis of the relationship between football and emigration , between identity and lost or found roots ”in public opinion . January 14 , 2016. Online: http ://www.op Opinion-pubblica.com/calcio-ed-emigrazione-lidentita-e-l identification/

Marchesini, Daniele. “Sport” in Bevilacqua, Piero – De Clementi, Andreina – Franzina , Emilio ( edited by). History of Italian emigration . Vol. II: Arrivals . Rome: Donzelli , 2009, pp. 397,418.

Meneses , Guillermo Alonso – Avalos González, Juan Manuel. “The investigation of the futbol y sus nexos con los estudios de comunicación : Aproximaciones y ejemplos ” in Comunicación y sociedad , (20), 2013, 33-64. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-252X2013000200003&lng=es&tlng=es http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/comso/n20/n20a3.pdf

Meneses , Guillermo Alonso – Escala Rabadán , Luis ( coord .). Offside / Fuera de lugar Futbol y migraciones en el mundo contemporáneo . Tijuana, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2015. Online: https://books.google.it/books?id=7hwQCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT343&lpg=PT343&dq=futbol+estudios+culturales&source=bl&ots=Y64qOTkxwg&sig=ACfHXXAvX_AxHXUdX_AxHdXUvEX_AxHxHxUvXHxUdXUdXHUXY 2ahUKEwjhzfuZn97oAhUow8QBHaslCsgQ6AEwCXoECAwQMg = # v = onepage & q =% futbol 20estudios 20culturales% & f = false

Meneses Cárdenas, Jorge Alberto. “El futbol nos une : socialización , ritual e identidad en torno al futbol ” in Culturales , vol. IV, núm . 8, julio-diciembre , 2008, pp. 101-140 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. Online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/694/69440805.pdf