Selections of The Land of Lost Dreams by Laura Pariani, translated from Italian to English by Mary Ritter and James Marks

Il paese dei sogni perduti, by Laura Pariani, is a collection of short stories that are based on conversations Pariani had with Argentine friends. Pariani is Italian but has spent extensive time in Argentina. Her knowledge of the region’s history and her personal experiences there shine through in both her fiction and non-fiction works, which are often set in Argentina and explore the experience of Italian immigrants there.

Translation of “La memoria cancellata” by Mary Ritter and James Marks

The introduction to the book, “La memoria cancellata,” tells the story of the Italian “everyman” in Argentina at the time. In this chapter, she tells of the experiences felt by many Italian immigrants to Argentina: leaving from the same Genoese port, enduring the same immigration procedures, feeling the same homesickness. By doing so, she unites their experiences into one cogent process of losing one’s identity and memory. At the end of the chapter, she highlights the importance of memory.

Cancelled Memory

There were some that left to fare la golondrina,[1] as they said in those days. They worked for a while on the other side of the ocean and then returned. We were children then, but we still remember their faces, even if we didn’t understand if they were satisfied or desperate. Smiling yet disdainful, for they had seen the world, they subtlety flashed their golden pockets watches. Those who went to America could afford to act this way– surly, suspicious, asking about their fiancés and wives who were at home, awaiting their return.

Never did we think it was an act. The idea never even crossed our minds. On the contrary, it beguiled us; saving money for the trip cent by cent, rationing food, selling the little gold we had, causing the women to cry with its parting.

From Genoa, we boarded fearlessly, with meager bundles. We watched with fury the lights of the city that became farther and farther away, and we cursed our damned destiny, the ungrateful homeland and the fleas. We intended to return and outlive the resentment for the padrone[2] that had denied us a loan, the tenant farmer[3] that had sucked the soul from our work, the priest that wouldn’t even give us a word of comfort, a State that only remembered us when it was time for the draft.

Then the ocean, different from every river or lake that we knew, so frightfully vast. Thirty days of seasickness, vomit, stench from the cargo hold, wails of young children, nightmares of the ship sinking and being devoured by fish. Southward, always headed south. Finally, Buenos Aires was on the horizon.

What had worried us from the beginning was the fact that no one knew what awaited us upon arrival. Enclosed by the enormous vaults of the Hotel de Inmigrantes,[4] we Italians asked questions amongst ourselves, and the response was always the same: “they say…” “some friends wrote that…” “I heard that…” None of us had actually seen this land with our own eyes. We relied on vague stories that spoke of a city bigger than the striking Genoa from which the barco[5]left. An immense and empty country left in the hands of godless indios.[6] But it was difficult to understand what the truth could be in a land where they called that huge sea of murky yellow water that we had just finished crossing a río.[7]

Then came the medical exam, and then we were divided according to our skills: only those with an artisan craft were permitted to remain in the capital of Buenos Aires. The others, us peasants, were sent to be colonos[10] of the “campo”[11] as the Argentines called the unwavering solitude of the plains that spread out from the city without end.

Those of us who were a bit more cunning[12] could remain in Buenos Aires, fixing for ourselves a makeshift home in the neighborhoods on the outskirts with immigrants from our regions in conventillos[13] There, passing through the tall and narrow doorway, one finds a stone patio with a well in the middle. Around the patio, a portico with the room numbers of each family, assigned based on number of family members, no more than more two rooms per family. Dark and crowded cuartos[14] without any ventilation but the front door, two toilets for more than a hundred people, a basin for washing both sheets and children, a communal kitchen with a couple fires that the women competed to use, and a corral for the goats.

But for those who had neither skill nor purpose nor a patron saint to protect them, matters were even worse. Embarking on shoddy westward bound cart, or on a steamboat that chugged slowly up an enormous turbulent river that they called Paraná, we confronted a mysterious space: the earth that lay before us wasn’t the imagined kingdom of gold and fortune we expected, but a savage horizon of empty plains. And, in the big green desert, the silence was broken, especially by the stifling screeches of big birds and the screeching howls of the wind, until the sun left the sky quickly bringing darkness, without however bringing peace. Could this foreign starry sky ever calm us?

We felt darkness in our hearts as we crossed a place without a soul because it lacked history. Forget a land to be conquered: we were just a bunch of scared people, terrorized by the distance and the emptiness. How can one start anew when they have abandoned their country, family, friends, festivities, and mother language? Did we leave behind the only things that mattered in life? It wasn’t an adventure because we weren’t adventurers, and once we arrived in the campo, we found ourselves in the periphery of the world, in hamlets smaller than the ones we left behind, amongst huts and roads of mud, with little metal placards to mark the tiny parcels of land assigned to us. It all crushed our dreams.

Because this is the truth: we came unknowingly from the other side of the ocean, almost as if we were only going to the market to sell produce from our vegetable garden, convinced that, en el final,[15] at the moment of weighing gains and losses, we only wanted to be buried in the villages where we were born.

Of course, we had to force ourselves to accept it, al fin y al cabo[16] we accepted that we would never be rich, that it was merely an illusion, a dream that pulled us away from Italy. The dream that lured the first ones to make the voyage, in which we felt like we might own a land of our own with borders past the horizon. To ride on horseback through our fields with the same air of superiority that we envied of the noblemen in our land.

But if life was tiresome every day and terrible for those of us who were destined to the campo, it also wasn’t easy for those who secured themselves a spot in the capital. They had to play the accordion in the budding places of that negrado[17]rhythm that they called tango, sweating all night from the starch of the white vest under the mended black jacket. Otherwise they were constrained to ganar moneda a moneda,[18]cleaning tripe in the frigoríficos[19] at the Riachuelo[20] with muscles stiffened by the cold and the damned smell of blood.

Hell of a life… even so, we ate, we ate, we ate, that this was the only thing that proved to be true: that in Argentina, meat was abundant, and one could finally satiate the hunger that had been there for centuries. And around the parrilla,[21] we sang in our broken Spanish:

Yo solo pienso en ser rico

per decar de trabacare

andarme con la familia

a l’Italia a descansare [22]

We were young. At home, in Italy, we left our mothers, girlfriends, sometimes no less than a wife and little children. In the beginning, we wrote letters in uncertain handwriting, we wanted to know how it was going for everyone over there on the other side of the ocean. We wrote of the problems of our new lives, we praised ourselves for our gains and for our future possibilities. Our words did not hold the malice caused by a mistake but the shame of not being able to make it in America like everyone at home expected us to.

Then, little by little, the tiredness of trying to create an impossible fortune beat us: we cut down on the letters, and in the end we stopped writing them all together. We learned the art of forgetting. The wonderful faces that were, the fondness that in the beginning of the separation made our hearts palpitate from nostalgia, the familiar places, even the words of the language we were raised speaking, all began to leave us little by little. We turned the page, and we became Argentine: with other women, under this different sky, with new words.

Letter from the Author:

All of the following stories, aside from one, came from conversations with Argentine friends during the year 2003. I wrote them with the awareness that, without memory, the present transforms into a time without the possibility for change or rebirth. Therefore, in these pages I mixed the public memory with individual memory: because a society that forgets is condemned to its own ignorance. In Argentina, el olvido, that is forgetfulness, moved more quickly than history in the last century, as was well said by Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Notes:

[1]“Fare la golondrina” was an expression used to describe Italian farmers who migrated from Italy to Argentina every year, working the harvest season in each country. In Italian, the word “golondrina” means barn swallow. Just as barn swallows migrate to South America in September and to North America in. April, to spend the warmest months in both areas, some Italian farmers would migrate every year, in order to spend the harvest months in both Italy and Argentina. George Epolito, “Golondrinas: Passages of Influence: The Construction of National/Cultural Identities in Italy and the Río de La Plata Basin of South America,” Taylor & Francis, August 24, 2012, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14608944.2012.702743.

[2] Italian for “landowner.”

[3] It can be assumed from this passage that the immigrants would be working under a tenant farmer, who’s goal was to produce as much as possible, without regard for the workers.

[4] The Hotel de Inmigrantes, or the Immigrant Hotel in Buenos Aires, was a place for just-arrived immigrants to stay for a short time until they found housing.

[5] Spanish for “boat.”

[6] Spanish for “Indians” meaning “Native Americans.”

[7] Spanish for “river”, which refers to the Rio de la Plata or the Plata River, in English. To Italians, it seemed as big as a sea, and the sentence goes to show how confusing it could be as immigrant in a place where they called what seemed like an ocean a river.

[8] Rio de la Plata is a river system and area of the same name that flows into the Atlantic Ocean, image from – https://www.garmin.com/en-US/p/154015

[9] The Immigrant Hotel, image from – https://turismo.buenosaires.gob.ar/en/otros-establecimientos/national-immigration-museum

[10] Spanish for “colonizers.”

[11] Spanish for “fields.”

[12] The original term used here was “gàbola,” which denotes lies or trickery.

[13] Spanish for “tenements.”

[14] Spanish for “rooms”

[15] Spanish for “in the end.”

[16] Spanish for “eventually.”

[17] Adjective form of “black” in Spanish. There is a racial connotation that denotes the African roots of tango music.

[18] Spanish for “living penny to penny.”

[19] Spanish for “refrigerators.”

[20] The Riachuelo was a meat processing facility, a commonplace job in Argentina at the time.

[21] Spanish for “grill.”

[22] Broken Spanish, noted by some Italianized verb endings, roughly meaning “I only think about being rich, To leave work, To go be with my family, To Italy to rest”

Translation of “Anni Settanta. I: I morti di Trelew” by James Marks

This chapter is based on a conversation between the author, Laura Pariani, and a woman by the name of Tanita whom she presumably encountered in Italy and conversed with while preparing for this book of stories and history. This telling is based on the Massacre of Trelew in which political dissidents of the government of Alejandro Agunstín Lanusse were killed in cold blood after a prison escape that did not go totally to plan. This was a time period in Argentina of many dictatorships, and this was not the last bout of killings to happen. The “Dirty War” that came a few years after had approximately 10,000 to 30,000 killings, of both political dissidents and regular citizens.[1]

The ’70s, I: The Dead of Trelew

“I wasn’t into politics at that point, it was 1972, I was too little. From my family I heard mentions of the ERP, FAR, andMontoneros[2], when my father talked about the newspapers. I barely knew who the guerillas were. They didn’t interest me. Do you understand? Back then they all seemed crazy, I was thirteen, I still had braids…”

I still remember the voice of Tanita well: it was high pitched like that of a young girl. She had arrived in Italy in 1981, after some time in Mexico. We had in common a love for comic strips and for calla lilies, those white flowers shaped like a funnel that were always too rare to find at a florist shop.

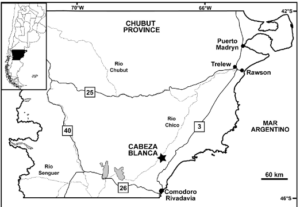

“Then, that day in the middle of August, we heard the news from a Uruguayan broadcast: Radio Colonia[3]recounted that that morning, roughly thirty political prisoners escaped from a maximum-security prison, in Rawson. When they escaped, they were headed towards the airport in Trelew, about thirty kilometers away.”

On occasion I saw some pictures of those two small towns in the province of Chubut, a Welsh enclave in the Patagonian territory: rolling hills battered by the wind, the Valdés peninsula in the distance with its seals and walruses. A tranquil place that seem removed from history…

“In the moment I thought of the soldiers humiliation, of that General Lanusse who governed us. Máxima seguridad[5], yeah right! Serves him right this blunder… But soon after, the radio correspondent added that only four or five were able to reach the Austral[6] flight that some accomplices had hijacked as a means for escape. The others arrived at the airport too late: there, they barricaded themselves in for a bit, attempting to resist the siege of the military. In the end, they gave up their guns and surrendered.”

That was it. By then, they must have already arrived at the naval base “Almirante Zar” in Trelew. In the meantime, a Chilean broadcast told of the hijacking of the aircraft and of six guerrillas (the most famous was Roberto Mario Santucho, founder of the ERP) who landed in Puerto Montt[7] with a request for political asylum.

“Argentine radio broadcasts however remained silent. Only the day after did they acknowledge a failed escape attempt, explaining that the fugitives, after being recaptured, were brought to a nearby naval base. Then, nothing else.”

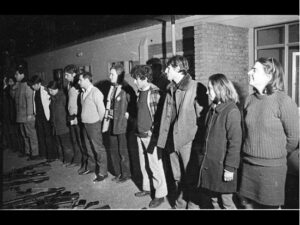

Of the nineteen that surrendered there remains only a single photo from the airport, taken at the moment they surrendered their arms to the lieutenant commander, Sosa: with the face of someone in waiting, between life and death. The military didn’t want to take hostages, unconditional surrender…

“Three or four days after, as I was coming back from school, my mother told me that on the eleven o’clock news, they said that one of the recaptured escapees tried to take a machinegun from a guard and fighting broke out: some had died. Gradually, as the hours passed, the number of dead told by the radio increased. On the five o’clock news, they confirmed that the prisoners all tried to escape at once and were mowed down by bullets. You get it? Habían caído todos[11]. Nineteen dead for an impossible escape, as the naval base was in the middle of nowhere… So, an implausible story. So improbable that not even my mother would believe it.”

But six survived the massacre; they were in bad shape, on the brink of death: the military had let them bleed out until medical attention arrived. The doctors were only notified of them ten hours after the incident. Three recovered – María Antonia Berger, Alberto Miguel Camps and René Haidar – they would go on to tell the real story.

“I felt shocked. I never thought the military would do this. ‘Son simplemente bestias’[12] said my father, astonished by the fact that the authorities, instead of bringing them to justice, they would rather just kill them. I felt a sudden disgust growing inside me for the world, for our leaders. I couldn’t understand how they ever came to do such a thing. Cuesta pensarlo. No se entiende.[13] The ferocity, the brutality…”

It is hard to even conceive that it would happen in a Roman Catholic and apostolic Argentina. Where all the members of the armed forces, without exception, made their first Communions, were married in the church, and surely confessed their sins regularly. Nineteen prisoners, both men and women, all young; Ana María Villareal, wife of Santucho, eight months pregnant… They were thrown into calabozos,[14] beaten, stripped naked, to then be assassinated.

In the end, to cover up the barbarities, they simulated an uprising, and the ley de fuga[15] was invoked. To top it all off, the Communique of the Navy were accepted and praised by the president for their actions, General Alejandro Agustín Lanusse, an honest and religious man as his biographies would claim.

“The next morning at school they were talking about murder. Everyone was still in shock, and worn out from it, some cried. The older ones organized an assembly; they recited off the names of the dead and every one of us responded: ‘Present! Hasta la victoria siempre!’[17] One of my friends said that this was the second worst massacre of Patagonia. You know, after that one in the 20’s with the peones[18]… sometime later the bodies were brought to Buenos Aires, I think they wanted to organize a funeral vigil at the union headquarters in my neighborhood, on La Plata Avenue. That afternoon I heard sirens, gunshots, a crazy commotion, and then the riot control tanks appeared: the police assaulted the place where the velorio[19] was happening, they launched teargas, they beat the families and destroyed the facility. All to stop the people from accompanying the bodies to the cemetery.”

And then? The lieutenant commander Luis Emilio Sosa, and the frigate lieutenant Roberto Guillermo Bravo, the responsible parties of the matanza[20] at the aeronaval base in Trelew, were sent to the Argentine embassy in Washington to hacer cursos[21] with special indemnity.

The tragic facts of Trelew came into my mind suddenly as I passed by a painting of mine, a little drawing that I drew while thinking of Tanita, many years ago. I believe that, on the back, there would also be a dedication to her and her memories from the seventies… It hangs in a corner, this little drawing: bodies torn to shreds, a baby with braids that stares at them, shocked and incredulous. Every now and then, I pause to look at it. Today inadvertently, I raised my eyes and Tanita came back to me, meeting me in the dark corridor that is memory. Who knows where she ended up? Her family moved to Germany, she wanted to graduate from a cinema school.

Strange how there are certain things, that in the moment go unobserved. For example, in those times – it’s been thirty years at this point – when I read Italian newspapers with superficial articles on the massacre at Trelew, I did not realize their importance. The unconceivable decision to kill the guerillas in cold blood – the “final solution” – to make them pay for the military’s humiliation. Then the implausible account of the facts… it seems to me now that in those times, the incapacity to justify such criminal conduct of the Naval officials could have influenced the following decision to carry on in complete secret the repressive plan in the coup of 1976. Yes, the nightmare of the Guerrasucia[22] began the 22nd of August 1972. Because not even the others, the refugees in Chile, could save themselves. Like Marcos Osatinsky, recaptured in ’75 and tortured in the police headquarters in Córdoba, and then – they say – skinned alive. His wife was also kidnapped in ’75 and held in the ESMA[23] together with their fifteen-year-old son. The other of her sons, seventeen years old, was killed during his capture. Or like Roberto Santucho – a young man in bloom, who I chanced upon reading the diaries of Witold Gombrowicz, who had him as a pupil in 1951 in Santiago de l’Estero[24] – captured and killed in ’76. Seven members of his family were killed, four vanished, nine took asylum elsewhere… Enough. No quiero ricordar más.[25]

Notes:

[1] “Argentina Declassification Project – The ‘Dirty War’ (1976-83).” Central Intelligence Agency. Accessed May 13, 2023. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/collection/argentina-declassification-project-dirty-war-1976-83#:~:text=During%20the%20Argentine%20government%27s%20seven,as%20well%20as%20innocent%20victims.

[2] Ejercito Revolucionario del Pueblo – The People’s Revolutionary Army, Las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias – The Armed Revolutionary Forces, and Montoneros – Movimento Peronista Montonero, were all left-wing revolutionary groups.

[3] Uruguayan radio station

[4] See the top right center area for view of Rawson and Trelew. Image from – Busker, Felipe. “-Map of the Chubut Province, Patagonia, Argentina, Showing the Location …” ResearchGate, 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-the-Chubut-Province-Patagonia-Argentina-showing-the-location-of-the-Bajadadel_fig1_335293341.

[5] Spanish for “maximum security”

[6] An Argentine airline

[7] A city in Chile

[8] Almirante Zar Aeronaval Base in Trelew, Image from –

“Bases En Chubut.” Avnaval – bases en Chubut. AccessedMay 13, 2023. https://www.histarmar.com.ar/Armada%20Argentina/AviacionNaval/BasesAeronav/BANChubut.htm.

[9] Prison in Rawson, Image from – Román, Emiliano. “Rawson.” A Sala Llena, October 27, 2012. https://asalallena.com.ar/rawson/.

[10] One of the last images of the prisoners at the airport. Image from – Caistor, Nick. “Massacre at Trelew: 50 Years On.” Latin America Bureau, August 22, 2022. https://lab.org.uk/massacre-at-trelew-50-years-on/.

[11] Spanish for “they mowed them all down”

[12] Spanish for “They are simply animals/beasts”

[13] Spanish for “It’s hard to comprehend, one cannot understand”

[14] Spanish for “jail cells”

[15] Extrajudicial killings

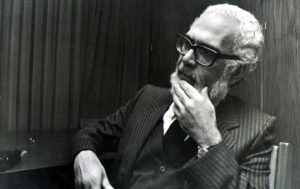

[16] General Alejandro Agustín Lanusse – Image from – Barrio, Facundo Fernández. “Las Actas Secretas de Lanusse.” El Cohete a la Luna, August 21, 2022. https://www.elcohetealaluna.com/las-actas-secretas-de-lanusse/.

[17] Spanish for “All the way to victory”

[18] Spanish for “peasants”

[19] Spanish for “vigil”

[20] Spanish for “massacre”

[21] Spanish for “to do coursework”

[22] Spanish for “Dirty War,” refers to the many extrajudicial killings in Argentina in the mid-70’s to early 80’s.

[23] The Argentine Naval Mechanical School which doubled as a clandestine detention center.

[24] A city in Northern Argentina

[25] Spanish for “I don’t want to remember any more.”

[26] The Argentine Naval Mechanical School, which is now a memorial for the human rights abuses of the final dictatorship. Image from – UNESCO. “Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos (Ex ESMA) – CIPDH – UNESCO.” CIPDH. Accessed May 13, 2023. https://www.cipdh.gob.ar/memorias-situadas/lugar-de-memoria/espacio-para-la-memoria-y-para-la-promocion-y-defensa-de-los-derechos-humanos-ex-esma/.

Translation of “Anni Settanta II: E di notte la paura” by Mary Ritter

This chapter, “And at Night, Fear,” features a conversation with Noemí Ulla (1940-2016), an Argentine writer, who discusses her experience of being a writer during the years of the dictatorship. She also references the experiences of other Argentine writers who experienced great persecution under the civic-military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976-1983.

[Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Rosario.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 7, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/place/Rosario-Argentina.]

[Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Paraná River.” Encyclopedia Britannica, March 14, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/place/Parana-River.]

The ’70s, II: And at Night, Fear

“I arrived in Buenos Aires at the end of the 60s. I came from Rosario – not a small city but still provincial – with big dreams.” The voice of Noemí Ulla scratches in the dim light of the living room of her apartment on the eleventh floor on Moreno Street, two steps from the Casa Rosada.[1] Photographs and paintings hung on the walls. The blinds, as always, were lowered to block out the reflection of the January porteño.[2] “I had just released a novel, Los que esperan el alba[3]. It was the winner of a competition in Santa Fe, and the prize was its publication. Then an essay, Tango, rebelión y nostalgia,[4] with the lyrics of songs of tango.”

[“Noemí Ulla.” Editorial Municipal de Rosario. Accessed May 14, 2023. https://www.emr-rosario.gob.ar/autor/noemi-ulla/.]

“But why did you leave the province?” I ask, sipping a very sweet Turkish coffee that Noemí had served me with a plate of little cookies.

“Who knows?” Short light hair, a white gown with a brooch pinned on the breast; her- delicate face gives the impression of fragility, which is decidedly negated by the tone of her voice, with which Noemí shares her thoughts, ideas, desires. A special atmosphere hangs in the room.

“Surely at the time Buenos Aires enchanted a young person: it was a splendid city. The publishing houses prospered, translating many works and producing magazines.”

I sensed nostalgia in her words. I understand you, I want to tell her. I also remember Buenos Aires at the end of the ‘60s. Frequently, the memories would flood my mind all of the sudden: illuminated window displays of Calle Florida,[5] afternoons at the Confitería Richmond with my mother, purchases from Harrod’s, the theaters of Corrientes surmounted by neon signs and overflowing with people. How is it possible that all that fervor, that progress that one sensed in this capital could disappear so suddenly? It seems incredible to compare the city of my memories with its actual decline; and something in my heart hopes that Buenos Aires could resurrect itself.

“I began to work for the Centro Editor de America Latina,” continues Noemí, “and then I supported myself by dedicating my life to teaching. But what I really loved was something else: my deepest love was, above all, for creative writing, especially magical realism. But in those times, no one wanted that: the dominant idea was that literature must focus on political commitment and social engagement. It was considered immoral to let the imagination run free. Therefore, my first collection of fantasy tales, Ciudades – that, amongst others, was liked very much by Silvina Ocampo[6] – came under ferocious attack. ‘But how?’ a Peronist friend asked me once. ‘How can you settle on fantasy as a person who has written an essay on the letras de tango?’[7] So the book, which was ready in 1974, waited for years, until 1983, to be published.”

She poured me a little glass of marsala. There was peace. The apartment is silent, yet vaguely resonant, almost overtaken by the humming of the city that surrounds it.

“They were the years of the dictatorship. A horrific experience for all. But the intellectuals suffered a particularly strong persecution: certain books were banned, taken from libraries and destroyed, and many writers and journalists were imprisoned or vanished.”

I think about Nunca más,[8] about the desaparición[9] of many intellectuals of that time. Oesterheld,[10] for instance, the author of Eternauta who was kidnapped. The government circulated misinformation to cover their tracks, saying that he was in Europe to receive an award. Haroldo Conti[11] and Rodolfo Walsh[12] come to mind too, who preferred to be shot than imprisoned. 36,000 desaparecidos[13] is a huge number, a quantity of bodies that I struggle to imagine.

“In those years, I happened to send one of my short stories to a contest with a panel of judges that included Onetti.[14] The story won second place. And you know the advice some friends gave me? ‘Don’t tell anyone that Onetti was on the panel!’ they told me, because he was a writer despised for his political ideas, disliked so much that he had to take refuge in Spain. We felt powerless, dispossessed of our own life. Every word that you said had to be carefully weighed because someone could denounce you … At that time, I was teaching, and during an inspection, a colleague denounced me as subersiva[15] Fortunately, I had the support of the director, who called that her and confronted her: “Well, now we’ll have a meeting between her and Noemí Ulla.” It was a real face to face. He asked her why she accused me, but the only thing that she told him was that I had friendships with intellectuals from the left and that I worked with left-wing publishing houses. Yes, this was true, I couldn’t deny it. But the director fearlessly defended me, keeping his composure, and he finished by ridiculing her.”

“And then?” I asked with bated breath.

“Nothing. Nothing happened. It was a miracle. But for a long time, I expected a car to come in the night and take me away. It had happened to other people that I knew. So, every time that I was reminded of the incident, the fear returned.”

I heard many others repeat this same feeling of apprehension: the racing heart, night after night, the perked ear, the muscles tensed from anxiety, the silence of the telephone, getting sleep only in the morning, when the radio started its brief and monotone messages on the reorganización nacional[16] A nightmare that lasted for years. A fear of speaking, thinking, writing. Years of silence just to survive. I think of the last scene from the novel Fuego a discreción from the Italian Argentine writer Antonio Dal Masetto,[17] when the protagonist, a boy living in the years of the dictatorship, ends up locked up in an empty cistern and, in an almost ritual act, kills a dove and uses its blood to write on the walls: amor ya no es una palabra, ahora la palabra es fuerza.”[18]

“And you never thought of leaving Argentina? I know that many intellectuals escaped …”

“Of course I thought about it. But I didn’t have money. I remember I wrote to another Argentine writer who had taken refuge in Spain, asking for advice. He told me sincerely that Spain was just recovering from its own dictatorship and that living there was its own complicated situation. But, in the end, it was a still question of money: I didn’t have enough to get there.”

The streetlights were slowly turning on outside the window as night fell. After the afternoon pause, Buenos Aires comes to life, as the oppressive heat of the day mellows. The pulled-up blinds reveal a multi-colored sunset of yellows and reds. A lilac-colored cloud unravels on the top of a skyscraper. It’s impossible to not compare the peace that is now with the terror that was in those years.

[Asokan, Ratik. “An Argentinian Novelist, out of Oblivion.” The Nation, August 22, 2016. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/antonio-di-benedetto-zama-out-of-oblivion/.]

“For me, things definitely turned out alright. Others’ lives were broken. For example, Antonio Di Benedetto,[19] one of the greatest Argentine writers. It was Juan José Saer,[20] my friend from Santa Fe and also a writer, that made me read, many years ago, El Silenciero and Zama. The stories shocked me, so much so that I wanted to a write an essay about Di Benedetto. In Buenos Aires at that time no one knew him yet because here in the capital they had always looked down on the province, and Di Benedetto, being from Mendoza, suffered the consequences. But I insisted: I began to collect news and reviews because I really wanted to write the essay. I also started a long correspondence with him. I finally meant Di Benedetto here in Buenos Aires when he visited the capital. I was struck by the news that he had been interned in a concentration camp. He was released after a year, following a large media campaign during which many public figures, like Victoria Ocampo[21] and Bioy Casares,[22] signed a petition. But by then, he was a different man: destroyed by torture, crushed by terror, with a sense of universal guilt that resulted in paranoia. He exiled himself: France, Spain, Germany… He returned in 1983, when democracy was first reinstated: they gave him a job that was not enough to live on, so much so that it made him deeply ill. So, after a little bit of time, he died. It was 1986.”

Notes:

[1] The office of the Argentine president.

[2]Porteño means “port city person” in Spanish. It refers to people who come from port cities, including Buenos Aires, Argentina. But in this sense, it personifies the heat of the summer sun in Argentina, where the seasons are reverse of the Northern Hemisphere.

[3] Ulla’s first novel, which she published in 1967. “Noemí Ulla,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noem%C3%AD_Ulla

[4] An essay published in 1967. Ibid.

[5] A major street in downtown Buenos Aires popular for its shopping centers and street performances. “Florida Street,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florida_Street

[6] Silvina Ocampo (1903-1993) was an Argentine short story writer. She is considered to be one of the greatest Argetine writers of all time, so it would be a great honor for her to enjoy one of Ulla’s books. “Silvina Ocampo,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silvina_Ocampo

[7] Spanish for “lyrics of tango.”

[8] A report produced by the Comisiòn Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) in 1984. The report was based on the commission’s investigations into the Argentine government’s forced disappearances of thousands of the country’s citizens. “National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Commission_on_the_Disappearance_of_Persons.

[9] Spanish for “disappearance.”

[10] An Argentine journalist and writer. His graphic novel, El Eternauta, is one of his most famous works. His comics acted as social commentaries on the dictatorships that plagued his native country, but unfortunately, as a result, he disappeared in 1976, likely kidnapped and murdered by the government. “Héctor Germán Oesterheld,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C3%A9ctor_Germ%C3%A1n_Oesterheld.

[11]An Argentine writer who disappeared in 1979. “Haroldo Conti,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haroldo_Conti.

[12] An Argentine investigative journalist who was killed by a group of Argentine soldiers in 1977. His most famous work is “Carta Abierta de un Escritor a la Junta Militar” (Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta), which criticized the economic policies of the Argentine dictatorship. “Rodolfo Walsh,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodolfo_Walsh#Death. “Carta abierta de un escritor a la Junta Militar,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carta_abierta_de_un_escritor_a_la_Junta_Militar

[13] Spanish for “disappeared” or “missing” persons.

[14] An Uruguayan novelist who was imprisoned by the Argentine dictatorship. “Juan Carlos Onetti,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Carlos_Onetti

[15] Spanish for “subversive.”

[16] This refers to the “Proceso de Rorganización Nacional” (National Reorganization Process), the military dictatorship that controlled Argentina from 1976-1983. “National Reorganization Process,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Reorganization_Process

[17] A writer born in Italy who moved to Argentina and eventually settled in Buenos Aires. “Antonio Dal Masetto,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Dal_Masetto

[18] A phrase in Spanish that translates to “love is no longer a word, now the word is strength.”

[19] An Argentine writer who wass imprisoned and tortured in the 1970s by the Argentine dictatorship. “Antonio di Benedetto,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_di_Benedetto

[20] One of the most important Argentine writers. “Juan José Saer,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Jos%C3%A9_Saer

[21] An Argentine writer. “Victoria Ocampo,” Wikipedia, last accessed may 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Ocampo

[22] An Argentine writer. “Adolfo Bioy Casares,” Wikipedia, last accessed May 13, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolfo_Bioy_Casares