A panorama view of the vineyard Casa de Uco located right at the foothills of the Andes. It serves as a representation of one of the more than 1,500 wineries in the region of Mendoza

You can’t think about Italy without thinking about wine. It is a product that is impossible to separate from Italian culture, history and traditions. When you think of Mendoza, the western region of Argentina, the production of wine also defines the culture, history, and economy of the area. In this blog post, I intend to show how the wine industry has developed in Mendoza, from its indigenous founders to the Spanish colonizers, until the arrival of immigrants from southern Europe (especially the Italians). In particular, I will examine the impact that Italian immigrants had on wine production during the greatest period of migration in Argentina, from around 1880 until 1915. You can see their extraordinary influence in various sectors concerning wine: the production, oenology and agriculture, commerce, education in viticulture and agriculture schools, and the technical, academic, mechanical and business skills that they brought with them and that they developed as new Argentine citizens.

Mendoza and Its Geographical and Climatic Characteristics

To understand why Mendocenean wine is so particular and why it has become a worldwide delicacy, it is necessary to understand the geographical and climatic characteristics of the region. The term terroir is used to describe the combination of factors such as soil type, climate, and the amount of sunshine the grapes receive which together define the specific taste of each type of wine. Mendoza is located at the foothills of the Andes, the mountain range that divides Chile and Argentina. The altitude of this region is very high; some grapes grow at altitudes of up to 1,700 m above sea level, but most are grown at around 1,000 m above sea level (Discover Mendoza Wines – VINOA). At this altitude, the temperature remains constantly very cool, which is excellent for preserving the grapes. In addition, the rarefied air allows the sun’s rays to penetrate the plants strongly and uniformly. The region is also very arid, given that the Andes block most of the precipitation that comes from the Pacific to the west. In a normal year, Mendoza receives about 20-25 cm of rain, very little compared to other wine regions, such as Piedmont, which receives 106-117 cm per year. Together, these factors contribute to the production of truly excellent grapes, and therefore, incredible wines (Discover Mendoza Wines – VINOA).

In the region of Mendoza, there are various wine production areas. The most important ones that contribute significantly to its wine output are the following: Lujan de Cuyo y Maipú is located in the center of Mendoza, where Malbec is grown at an altitude of 650 to 1,070 m. above sea level. There is also the Uco Valley, which is south of Maipú, and where the grapes are grown at the highest altitude, 1,700 m. above sea level. Further south lies San Rafael y General Alvear, where Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Malbec are grown (Discover Mendoza Wines – VINOA). Each region varies slightly from the others, however the same general characteristics define this area of South American wine production.

This map shows where the most important wine regions are located in Mendoza

Which Wines are Produced in Mendoza?

Let’s pause for a moment to talk about the typical wines of the region, after which we will talk about their origins. For white wines, Mendoceneans are most famous for the production of Chardonnay, which is known for its freshness and acidity. These same characteristics also define Riesling which is another important wine of the region. Additionally, Torrontes is a wine of Argentine origins, whose grapes grow at high altitudes. This wine is also known for its freshness as well as being particularly fragrant and aromatic. The red wines produced in Mendoza are Malbec, Tempranillo and Cabernet Sauvignon. They are all characterized by their robust and full-bodied taste. Malbec is the most important wine in the region; the first vines of Malbec were planted in the first half of the seventeenth century. Tempranillo is a varietal brought by the Spaniards, and Cabernet Sauvignon is of French origins (Discover Mendoza Wines – VINOA).

Despite the various origins of these wines, it is clear that Argentines have developed advanced techniques and have built a formidable industrial system which is now one of the most important players in the international wine trade. In fact, it is the fifth largest wine exporter in the world; it contributes 1.5 million tons of wine to the global market every year. 2/3 to 3/4 of Argentina’s annual wine production (around 1,240,000 bottles) comes from the Mendoza region, showing the strength of the industry and the concentration of wine expertise that exist here (Expedia). In addition, Mendoza’s wine production alone makes up 1.3% of the country’s GDP (UN Video). Clearly, the Mendoza wine industry is one of the most important industries in all of Argentina. But how did it become such a large player internationally? Now, we will focus on the history of Mendoza and the figures who contributed to the development of its formidable wine industry.

I. The Indigenous Population and the First Spanish Colonizers

An examples of the acequías that can be seen throughout the city of Mendoza and that were constructed by the huarpes people many centuries ago

Before European colonizers arrived in the Andes, the indigenous group called the huarpes occupied the land. The members of this group settled in the area at the beginning of the fifth century AD. To water their crops, they created irrigation channels that collected the water that melted from the snow-capped peaks of the Andes mountains. This technology would come to revolutionize the agricultural system in the region, and when the Spanish colonizers arrived in Argentina in the sixteenth century, they appropriated these channels (but massacred the huarpes) for their agricultural needs. Now they are called by the Spanish name, i.e. acequías (Expedia). The first vineyards in this region were founded by the Jesuit missionaries around the mid-sixteenth century and were located next to their monasteries (VINOA).

II. The Founding of Mendoza and the Beginning of its Commercial Production of Wine

Before being an Argentine city, Mendoza was founded in 1561 by the Spaniards as a territory in the domain of the Kingdom of Chile. From 1561 to 1776 it remained under Chilean control (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte, 3). Mendoza and Chile share the Andes, and have historically worked together to produce and sell wine. They grew Criolla grapes for wine, but the wine low-quality. The wine that Mendocenean winemakers produced was sold in other Argentine cities, such as Córdoba, Buenos Aires and Santa Fe. In this pre-modern period, they transported the wine in carts in bottles made of ceramic or leather. They brought wine to the east coast of the continent as early as the eighteenth century.

The wine production process prior to the nineteenth century was similarly rudimentary; winemakers first had cows stomp on the grapes to extract their juice; then, they passed the grape must through the hair of the cow’s tail, then separating the skins from the must (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte, 5). After that, they put the liquid in the containers and left them there to ferment. After that, they used a piece of perforated leather to separate and remove everything other than wine. They bottled the wine and then closed it with lime, plaster, or mud. Clearly this process was very artisanal, but despite the slowness of the process, winemakers in Mendoza were able to create a surplus that, in as early as the eighteenth century, was exported all over the continent of South America.

III. The 19th century in Mendoza – An Industry that Begins to Transform

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the wine industry saw a 50% increase in exports from Mendoza, showing the continued centrality of wine to the region’s economy (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte, 6). The dated techniques had been replaced by more innovative ones; winemakers began using wooden barrels instead of ceramic containers. In addition, the Moscato and Criolla wine types had been replaced by Malbec, which would become the most important wine grown in Mendoza. In 1830, there were about 1,000 hectares of vineyards in the region (VINOA). After the end of the Rosas dictatorship in 1853 and after more than twenty years of insecurity for winemakers, winemaking had re-emerged as a robust industry with many economic opportunities.

At the same time, a large wave of immigrants had reached the shores of Argentina in the port of Buenos Aires. From 1853 until 1910, seven million immigrants settled in the country; a large percentage of the group remained in Buenos Aires or went to the Pampa, however many went to Mendoza to commence their new lives (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte, 7).

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Argentina needed manpower for the agricultural and industrial development of the country, however, some Argentine presidents, such as Sarmiento, Avellaneda and Roca, preferred immigration from Northern Europe rather than from the Latin cultures of the Mediterranean (South America Wine Guide). In the end, however, the people who needed work and who, for a variety of reasons, could not continue to live in their homeland were the ones who immigrated to Argentina. For the most part, they were southern Europe, originating overwhelmingly from Italy and Spain. The three presidents obviously did not think about the excellent knowledge of winemaking that immigrants from both countries had that they could utilize to strengthen Argentina’s wine industry.

The arrival of these people not only allowed Mendocenean wine production to continue, but also led to significant transformations and developments of the sector. Although there had been a long history of winemaking in Mendoza, the wines they produced were not as high quality as the European ones; Italian immigrants, especially those from Northern Italy such as Piedmont, Valle d’Aosta and Veneto, knew well how to make great wine, and in need of work, they sought opportunities in wine production. Some even brought vines with them from their homeland and then tried to grow them here in the new land (South America Wine Guide). Many arrived with a great technical knowledge of wine-making machinery was put to use in Mendoza. They also arrived with a great desire to drink wine, as per tradition in their country of origin.

IV. Italians and Italian Expertise as Essential Contributors to Mendoza’s Viticulture

Italian immigrants comprised a population of both wine experts and wine consumers. This caused a large increase in domestic demand for wine in Argentina, and luckily there existed a group well prepared to meet this demand. In 1885, in the early years of the first large wave of Italian migration, the railway connecting Mendoza to Buenos Aires was built (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Segunda Parte, 1-2). This new mode of transportation was necessary both for the development of the wine industry in Mendoza and for giving European immigrants the opportunity to reach the Andean city. Remember that these same Italians would have formed the majority of the workforce in the vineyards.

The railway revolutionized the wine trade; while in the past it took two months to travel by wagon from one city to another, now it only took two hours. The ability to produce a larger quantity of wine and to transport it quickly by train offered the winemakers of Mendoza the opportunity to considerably increase their output. In fact, in this period, production has skyrocketed; in 1910, there were about 45,000 hectares of vineyards in the region, and in 1914, the cellars of Mendoza produced 500 million liters of wine (La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte, 2). These impressive numbers were largely thanks to the Italian presence in the region. There were also many Italians who had an impact on the economy and the creation of the middle class in Mendoza as owners of small businesses they founded offering services and expertise they brought from the homeland (South America Wine Guide). Mendoza, at the beginning of the twentieth century, had a very large population of foreigners (in 1914, only 56% of the region’s population were native Mendoceneans), which contributed to a rather diverse environment (Vázquez 548).

The Most Important Italian Names in Mendoza’s Wine-Production Industry

Here it is important to mention the names and the stories of the Italian winegrowers who ushered in a new period of economic success for Mendoza and its wine production.

Antonio Tomba

The first is Antonio Tomba, born in 1849 in Valdagno, in the province of Vicenza. His family had a winery, so from there he acquired the wine knowledge that he would bring with him to Mendoza in 1873, when he left the port of Genoa to embark on the journey of his new South American life. When he settled in Mendoza, he met and then married the daughter of the Pescara family, a family of noble and wealthy Italian immigrants. On the land he received from his wife Olaya’s father, he founded a very large and successful wine company. He even sent for his brothers Gerónimo, Francisco, Domingo and Pedro from Italy to work with him in Argentina in the winery. Tomba began to export wine to Italy, creating a commercial link between the new home and the homeland and supporting a continued cultural connection. He also developed many new systems for grinding and filtering wine, which would revolutionize the wine production to follow (Gil, “Antonio Tomba: an Italian with espíritu ‘bodeguero'”). Furthermore, when the writer and scientist Gina Lombroso (1872-1944) traveled to Argentina in the early twentieth century, she met Antonio Tomba, and described him this way:

“Fu un italiano, il Tomba, un veneto, pratico della fabbricazione del vino, che rialzò, a quel che ci dissero, le sorti della vite. Il Tomba capì che la ragione per cui il vino a Mendoza non riusciva, era il caldo eccessivo al tempo della vendemmia, il quale arrestava il fermento nel momento che l’uva stava nelle tinozze; egli organizzò nelle sue cantine dei frigoriferi capaci di riparare a questo inconveniente e fabbricò così, del vino buono, che vendette a prezzi discreti; in pochi anni egli riuscì a fare adottare il suo vino dalle masse” (Gina Lombroso – Nell’America meridionale 248-249)

Three of the players of Club Deportivo Godoy Cruz Antonio Tomba, known simply as Godoy Cruz

Today, Mendoza’s soccer team is called Club Deportivo Godoy Cruz Antonio Tomba in honor of the important entrepreneur-winemaker.

The Italian winemaker Felipe Rutini

Another entrepreneur who contributed to the wine industry was the Italian Felipe Rutini, who arrived in Argentina in 1889 and founded his winery a few years later in 1895 (South America Wine Guide). It was called Bodega La Rural and it was also highly successful. Today, there exists the Bodega de Rural Museum in Mendoza, which has examples of old winemaking machinery from the time of Felipe Rutini.

The winery once owned by Juan Giol, which now exists as el Museo Nacional del Vino y La Vendimia in Maipù

The businessman, Juan Giol, also established his winery here in Mendoza. In 1887 Giol and Bautista Gargantini became commercial partners, and together bought a piece of land in Maipú. They produced their first wines in 1898 and in 1904 they became the richest winemakers in the world (Etchevers, “The Former Giol Winery – Maipú, Mendoza”). At its peak, the winery and vineyards, which were called La Colina de Oro, occupied approximately 260 hectares in the heart of Maipú. In fact, in 1911, the winery produced half of the total wine production in the country of Argentina and distributed its wines everywhere in the country. In 1917 Giol sold the winery, and subsequently returned to Italy to live with his family. The desire to return to the homeland at some point remained with almost all immigrants. Now what remains from Juan Giol’s wine empire is “El Museo Nacional Del Vino y la Vendimia” in the Casa de Giol in Maipú (Etchevers, “The Former Giol Winery – Maipú, Mendoza”). Here you can see how much Italian immigrants were able to excel in wine production after they settled in Mendoza.

La Escuela Nacional de Vitivinicultura (The National School of Viticulture)

Italians were also very present in the education of agriculture and enology, both as educators and as students. In Mendoza, the “Escuela Nacional de Vitivinicultura” was founded in 1896 to educate the next generation of Argentine winemakers and to continue the economic development of the region which had always been closely linked to the wine industry (Vázquez 544). The school employed many Italians or Argentines of Italian origins such as Renato Sanzín, the professor and botanical pathologist at the school (Vázquez 547). There was also the Italian Modestino Jossa, enochemist and director of the laboratory at the school, who then became the technical director at the Arizú cellar, also founded by Italian immigrants. A large part of the students were descendants of Italians (Vázquez 549), and thanks to this education, they were able to find work at the administrative level in wineries or become owners of companies. Below, we can see a chart that outlines the courses that were offered at the Escuela Nacional de Vitivinicultura:

Source: Vázquez, “LA RECEPCIÓN ITALIANA EN LA EDUCACIÓN AGRÍCOLA Y EN LA DIFUSIÓN DE CONOCIMIENTOS TÉCNICOS PARA LA VITIVINICULTURA DE MENDOZA, ARGENTINA (1890-1920),” 546.

Study Abroad

Another important aspect of education at the Escuela was the offer of scholarships to six graduates who were sent abroad to Europe for a year to deepen their wine knowledge. Among the destinations were Montpelier in France or Alba or Conegliano in Italy. The government of the province of Cuyo provided these scholarships, and in return, when graduates returned to Argentina, they worked for the government for four years, providing wine knowledge to spread what they had learned abroad to enrich the wine industry of the region. The technological and scientific knowledge they had learned in Europe had to be modified to adapt it to the different conditions present in Mendoza (Vázquez 549). More than half of the students studied in Italy; this figure confirms the Italian influence on Mendoza’s wine production at the beginning of the twentieth century, and how Italian wine knowledge was still very useful at that time (Vázquez 549).

The Next Generation of Italo-Argentine Winemakers

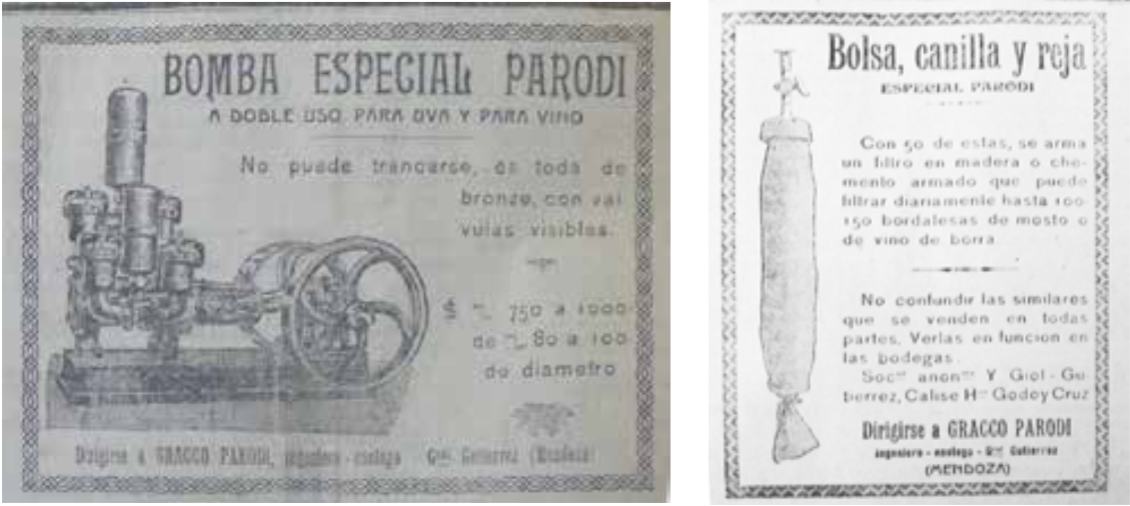

Graduates of the Escuela Nacional de Vitivinicultura, many of whom were Italian, contributed a great deal to the wine sector in the future. They have become directors, managers, presidents of wine associations, professors, collaborators, consultants, winemakers, entrepreneurs, and some worked within the government, as in the Ministry of Agriculture. After the 1903 crisis that ravaged the wine industry, the government of the Cuyo province requested the assistance of Italian wine experts to help improve the industry so as to avoid the same mistakes that had contributed to the previous crisis (Vázquez 553). In 1903, the Italian winemaker Gracco Spartaco Parodi was hired at the Bodega Tomba (founded by Antonio Tomba), which at the time was the largest wine producer in Mendoza. Subsequently, in 1910, the Italian Adriano Fugazza, another wine expert, took over for Parodi as enologist for the winery. Clearly Italian wine knowledge was still very prestigious in the eyes of the Argentines.

Source: Vázquez, “LA RECEPCIÓN ITALIANA EN LA EDUCACIÓN AGRÍCOLA Y EN LA DIFUSIÓN DE CONOCIMIENTOS TÉCNICOS PARA LA VITIVINICULTURA DE MENDOZA, ARGENTINA (1890-1920),” 557.

Parodi himself was also an inventor of technologies and wine machines, and created “La Bomba Especial Parodi de bronce” and “El dispositivo de bolso, canilla y reja” which adapted European technologies to the needs of the winemakers of Mendoza (Vázquez 557). The most important wineries in the region, such as Giol, Galise, Tomba and Toso (which were mostly founded by Italian immigrants), bought and used these inventions. Other wine inventions created by the Italians for use in Mendoza were the Garolla grinders and the Marelli pumps (Vázquez 556). Many winemakers and wine entrepreneurs in Mendoza wanted to use machines made in Italy, showing the influence and continuous presence of Italy in the Argentine wine industry in the early twentieth century. The demand for these devices created a transatlantic market between Italy and Argentina, which has served to maintain the links between the new world and the homeland (Vázquez 555).

The reality, however, the viticultural and winemaking link between Italy and Mendoza has not remained intact as strongly as it did in the early twentieth century. I would be negligent, however, not to mention the names of the wineries in Mendoza that still bear an Italian name and that still retain their Italian roots. Bodega Lagarde is a winery founded in 1969 by the Pescarmona family that came from Italy and is now managed by Sofía and Lucila Pescarmona, the third generation of the family (Pasado & Presente, Bodega Lagarde). The Catena Zapata winery is also of Italian origins, founded by the Italian immigrant Nicola Catena in 1902 (The Beginnings, Catena Zapata). Finally, the winemaker Alessandro Speri, who comes from a family of winemakers in Valpolicella, in the province of Veneto, came to Mendoza in 2002 to start a new wine company in Argentina. His father, Benedetto, is a fifth generation winegrower, so this wine knowledge is well rooted in the family (“El Hijo Prodigo”, Alessandro Speri Wines). Although there are other wineries in Mendoza that are managed by Italians or that bear an Italian name, these three show how the wine legacy which was brought from the Italian peninsula to the Andes of Mendoza over a hundred years ago has endured.

Cin cin! Salud! Or, better yet, both!

Bibliography

“Argentina: Home of Malbec Wines.” Youtube, uploaded by United Nations, 21 Dec. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xsM5WPnivgM.

“Discover Mendoza wines – VINOA.” Youtube, uploaded by Vinoa, 4 Feb. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k1FoEXPe1vQ.

“El Hijo Prodigo.” Alessandro Speri Wines, www.elhijoprodigowinery.com/alessandro-speri/el-hijo-prodigo/.

Etchevers, Pablo. “The Former Giol Winery – Maipú, Mendoza”. Welcome Argentina, www.welcomeargentina.com/maipu/giol_winery.html.

Gil, Cielo. “Antonio Tomba: Un Italiano Con Espíritu ‘Bodeguero.’” ItMendoza, 4 Sept. 2019, mendoza.italiani.it/scopricitta/antonio-tomba/.

“Gli Italiani in Argentina.” Rapporti Paese, Ministero Degli Affari Esteri, Apr. 2008, http://www.esteri.it/mae/doc_osservatorio/rapporto_italiani_argentina_logo.pdf.

“Italy.” Mendoza Travel. Accessed April 8, 2020. https://www.mendoza.travel/en/italia/.

La Cultura De La Vid y El Vino. El Fondo Vitivinícola Mendoza, http://www.fondovitivinicola.com.ar/page_educacion.php.

“La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Primera Parte.” Mendoza, a través De Su Historia, by Roig Arturo Andrés. et al., Caviar Bleu, 2004.

“La Vitivinicultura En Mendoza: Segunda Parte.” Mendoza, a través De Su Historia, by Roig Arturo Andrés. et al., Caviar Bleu, 2004.

“Mendoza Vacation Travel Guide | Expedia.” YouTube, uploaded by Expedia, 18 Aug. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9XNjXgM6FHo.

Nicoletti, Antonio. “Antonio Tomba, Start-Upper Ante Litteram.” Lo Zibaldone Economico –Spazio di Economia, Cultura e Cittadinanza, June 26, 2018. http://www.zibaldoneeconomico.eu/2018/06/antonio-tomba-start-upper-ante-litteram/

“Pasado & Presente.” Nosotros, Bodega Lagarde, www.lagarde.com.ar/nosotros/pasado-presente.

The Beginnings. Bodega Catena Zapata, www.catenawines.com/begginings.php.

Vázquez, Florencia Rodríguez. “LA RECEPCIÓN ITALIANA EN LA EDUCACIÓN

AGRÍCOLA Y EN LA DIFUSIÓN DE CONOCIMIENTOS TÉCNICOS PARA LA VITIVINICULTURA DE MENDOZA, ARGENTINA (1890-1920).” Mediterranea – Ricerche Storiche 26 (December 2012).

Yeomans, Clorrie. “A Journey through Argentine Wine History: Guide to Wine in Argentina.”

South America Wine Guide, September 13, 2019. https://southamericawineguide.com/a-journey-through-argentine-wine-history/.

Yeomans, Clorrie. “The History of Mendoza & Its Italian Wine Influence: Interview with Top Historian, Professor Cueto.” South America Wine Guide, August 15, 2019. https://southamericawineguide.com/the-history-of-mendoza-its-italian-wine-influence-interview-with-top-historian-professor-cueto/.

Image sources:

www.media.winefolly.com/mendoza-wine-map.jpg

www.winefolly.com/grapes/chardonnay

www.winefolly.com/grapes/riesling

www.winefolly.com/grapes/torrontes

www.winefolly.com/grapes/malbec

www.winefolly.com/grapes/tempranillo

www.winefolly.com/grapes/cabernet-sauvignon

www.d2v76fz8ke2yrd.cloudfront.net/media/ecs/global/magazine/story-images/020417/CasaDeUco-bg.jpg

www.mendozapost.com/nota/8159-quieren-que-las-acequias-mendocinas-sean-patrimonio-universal/

www.betrush.top/2018/07/23/godoy-cruz-vs-defensores-unidos/

www.welcomeargentina.com/maipu/giol_winery.html

www.southamericawinegide.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/felipe-rutini-min.jpg

www.zibaldoneeconomico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Tomba2-1024×576.jpg