What motivates migrant workers to move? How do they know where to go in order to find places to work? What kind of influence are Latino migrant workers having on the places they travel to?

A road less traveled

The route that migrant farmworkers take is generally the same year after year. However, there are a multitude of factors that affect the migration route and where people decide to move after they are done in one place. The most important factors that affect the migration pattern are:

- How the workers are treated and paid,

- How strict law enforcement is, and

- Whether or not they are travelling with others, be it family, a small group of other workers, or alone.

Travelling is the most important aspect of a migrant worker’s lifestyle and experience in the U.S. When I was speaking to Marta I asked how she traveled with the kids and their belongings and she replied,

“Siempre tratamos de salir como en la noche, o salimos en la tarde. Sabemos que los niños nos va dar guerra un ratito, unos dos tres horas y luego se duermen y duermen toda la noche. Y pues como queda en la noche está más tranquilo y más fresco. Es mejor en la noche. En el día pues entra el sol y hace más calor, hay más tráfico, todo es más…no es lo mismo. Y como es viaje largo, pues tratamos de salir de tarde para llegar por ahí de mediodía llegamos a.. del otro día, pues toda la noche manejando.”[2]

“We always try to leave in the night, or we leave in the evening. We know that the kids are going to fight us for a little while, maybe two or three hours but and then they fall asleep for the whole night. And since it’s in the night it’s more calm and fresh. It’s better in the night. In the day the sun is out and it’s warmer, there’s more traffic, everything is more…it’s not the same. And since it is a long trip, well we try to leave in the evening so we arrive there around midday we arrive at… the other day, driving all night.”

The unspoken understanding in her response was that during the night there are fewer police on the roads and fewer chances of getting pulled over for any reason.

In circular motion

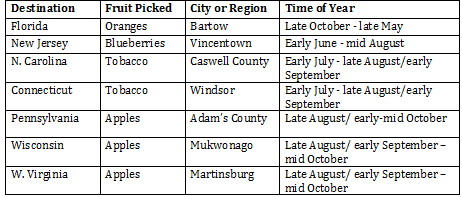

The cities and areas that migrant farmworkers travel to for work are all part of a non-official, but well-defined route or circuit for Latino migrant farmworkers. When the work in one area finishes, migrant workers pack their few belongings and move on to the next destination in search of a new job that they will work until the season is over. The stops that migrant farmworkers might take on the East Coast can differ depending on a variety of factors, however there is a consistent, well-defined general route that is followed. From the interviews conducted for this project, I learned that there are three main stops along the circuit. The first stop is in Florida, home base for the majority of the farmworkers at BB, for the orange and citrus season. The second stop is in New Jersey for the blueberry season. The third and final stop is in Pennsylvania for the apple season. Each place has unique characteristics, advantages and disadvantages, which all add to the migrant farmworker’s experience.

Florida

On the East Coast circuit, Florida is generally the first stop, or the place many migrant farmworkers begin their journeys. This is also where the most time is spent during the year because the season is longer. The citrus harvest in Florida lasts from late October to late May, nearly seven months picking oranges and other citrus fruit. When Marta was asked what it was like picking oranges, she explained:

“Casi viene hacienda lo mismo. Bueno es más….yo digo que es más matado, no sé si es. Porque, si cuesta..es más trabajoso que las manzanas. Aquí si fuera, bueno las manzanas…es trabajoso porque pues tiene…como uno anda en el grupo tiene uno que andar corriendo conjunto con la gente si no te quedas, si no, como que no avanza.”[1]

“It’s almost the same thing. Well it’s more…I say that it’s harder, I don’t know if it is. Because, it is tolling…it’s more work than the apples. Here is it was…well the apples…it’s hard work because you have to…one goes along with the group and has to stay running with the people and make sure you don’t stay behind, it just doesn’t advance.”

She explains that picking oranges is more complicated and harder work because the way they are instructed to pick requires that they after a truck with a large group of people. Sometimes, if a worker is not quick enough, they get left behind and have to stop working for the day because the truck will not wait. This can be extremely discouraging for the workers, but Marta says she thinks that they do it on purpose in order to force everyone to work faster. Many other workers, including the men, commented on the difference between the apple harvest and the orange harvest, and often explained how much more  tedious and difficult it was picking citrus, hinting at the fact that working and living in Florida was not the preferred job choice for many people. This attitude toward the work in Florida also reflected on how they felt about life in Florida in general. In another interview conducted by Aidan Gaughran, JJ Luceno and Rachel Gilbert, a woman explains that in Florida, camps are not always provided to the workers, as they are in Pennsylvania or New Jersey. In Florida the family must rent an apartment or small house to stay in during their seven months there.

tedious and difficult it was picking citrus, hinting at the fact that working and living in Florida was not the preferred job choice for many people. This attitude toward the work in Florida also reflected on how they felt about life in Florida in general. In another interview conducted by Aidan Gaughran, JJ Luceno and Rachel Gilbert, a woman explains that in Florida, camps are not always provided to the workers, as they are in Pennsylvania or New Jersey. In Florida the family must rent an apartment or small house to stay in during their seven months there.

“Allá es diferente porque allá no vivimos en campo. Allá vivemos en trailer; rentamos. Allá no estamos como aquí, que estamos todos juntos. Allá cada quién llega, busca su renta, no te van a rentar.”[2]

“Y luego… na’ más trabajas pa’ pagar la corta, pa’ pagar la salida, como… no, está difícil… está más difícil allá a veces. Porque allá gana uno poquito; paga uno renta que son unos quinientos al mes; paga uno luz, que viene más de cien; paga uno agua, que son más de cincuenta, cada mes, y ¡gana uno poquito!”[3]

“There it is different because there we don’t live in a camp. There we live in a trailer; we rent. There is not like here, where we are all together. There whoever arrives looks for their own rent, and they don’t rent to you.”

“And then…all you do is work to pay the court, to pay the exit, like… no, it’s hard… it’s harder there sometimes. Because there one makes very little; one pays rent which is five hundred a month; one pays the light which is over one hundred dollars a month; one pays the water which is more than fifty, every month, and one makes very little!”

Marta explains that they make much less money in Florida because they have to pay rent, light, water, etc., and when everything adds up they have little to spend or save. Predictably, Florida and the orange harvest are one of the least favorite areas of work for migrant workers on the route.

Nueva Jersey

The second stop along the general route is in New Jersey for the blueberry season, although there are alternative stops along the circuit during this same summer (late June or early July through late August) time frame. For example, alternative summer stops in the Mid-Atlantic area might be made in Connecticut or North Carolina. However, almost all of my interviews confirmed that New Jersey was the strongly preferred summer stop, if possible.

New Jersey (or other Mid-Atlantic locations) is also the shortest stop along the route  because the harvest period for blueberries is very quick. Workers will be in New Jersey over the summer, generally between early June to mid-August. Blueberries are easy fruit to pick, as Marta says, “es facilito para toda la gente… No tiene uno que cargar nada pesado. Nada más que la ‘basketita’”.[4] (“It’s easy for everyone… You don’t have to carry anything heavy. Just the basket.”) In addition to the relative ease of the labor, Marta thinks, “Las semanas que uno trabaja, trabaja bien. Son bien trabajadas ahí.”[5] (“The weeks that one works are worked well. It’s good work there.”) These feelings towards work in New Jersey also resonated amongst the other workers. Unless they know in advance that the blueberry season is going to be bad (for climactic reasons), migrant farmworkers want to make a stop in New Jersey and to be hired for the blueberry season.

because the harvest period for blueberries is very quick. Workers will be in New Jersey over the summer, generally between early June to mid-August. Blueberries are easy fruit to pick, as Marta says, “es facilito para toda la gente… No tiene uno que cargar nada pesado. Nada más que la ‘basketita’”.[4] (“It’s easy for everyone… You don’t have to carry anything heavy. Just the basket.”) In addition to the relative ease of the labor, Marta thinks, “Las semanas que uno trabaja, trabaja bien. Son bien trabajadas ahí.”[5] (“The weeks that one works are worked well. It’s good work there.”) These feelings towards work in New Jersey also resonated amongst the other workers. Unless they know in advance that the blueberry season is going to be bad (for climactic reasons), migrant farmworkers want to make a stop in New Jersey and to be hired for the blueberry season.

As for home life in New Jersey, many farms give the workers the option to live at a camp on the farm. However, instead of being able to cook their own food at the camps, they buy premade meals from a chef employed by the farm or they pay a fee to eat in a cafeteria where the food is also prepared for them. Marta explains,

“Bueno, sí uno quiere arrendar, puede arrendar para vivir mejor, para hacer comida porque ahí no hacemos comida ahí en el campo. Este, está la cocina grande y ahí pagan cocinera o cocinero para hacer comida. La hacen comida a toda la gente, porque sí es demasiada gente que llega ahí. Son como, llegan, a ver, hasta dos cientas personas en un campo de esos. Y ese le pagan a la cocinera y dos ayudantes así para que hacen la comida para todos, toda la gente. Y después a uno ya no lo dejan entrar a la cocina con otros a la cocina si no ocupar la cocina. Le digo si quisieramos sería bien caro pagar, pues va pagar depósito uno, pagar depósito de luz, de agua, de todo porque…Para arrendar tiene que dar depósito y todo eso. Y a pagar la luz también y luego también ya es más difícil porque si quiere uno bajar luz y agua le piden papeles, pero nosotros no tenemos papeles, y este…no ya no. Y sale demasiado caro, y por eso no. Eso no más, dos meses le digo, y después para acá.”[6]

“Well, if you want to rent, you can rent to live better, to make food there because we don’t make food there in the camp. There’s the big kitchen and there they pay a cook to make food. They make food for everyone because it’s too many people who go there. There’s like, let’s see, up to two hundred people in one of those camps. And they pay the cook and two helpers so that they make food for everyone, all the people. After they don’t let anyone go into the kitchen. I say that if we wanted to it would be very expensive to pay, you have to pay a deposit, pay the deposit for light, for water, for everything because…To rent you have to pay a deposit for all of that. And pay the light also and it is more difficult because if you want to get light and water they ask you for papers, but we don’t have papers, and so…we can’t. It’s too expensive, and because of that no. That’s it, two months I say, and then back here.”

New Jersey is one of the spots on the route that the workers do enjoy passing through. There is always enough work for many people, the labor is not as intensive as oranges or apples and it is for a short period of time, so people do not get bored with the work.

Pennsylvania

Finally, the last spot on the general East Coast route is Pennsylvania. The season in Pennsylvania lasts between late August and early to mid October, depending on when the picking is completed at an orchard and when people are ready to move on to the next place. When the workers arrive in August it is very hot still, but the picking starts immediately. Fortunately, apples stay ripe on the trees for a long time, giving the orchards and the workers time to finish. With the Mosaic class, we had the opportunity to go to an orchard towards the end of a work day to see how the picking was done. I was surprised at how quickly everyone moves, often running to the trucks to empty their satchels and then continue picking. There are no formal rules on how to pick the apple, only an unwritten rule to not get in anyone’s way. In order to get to the apples, the workers jump, climb the trees and move around tall, rickety wooden ladders. When they are done, they take their bag of apples to a parked truck with enormous wooden crates and empty them. Attached to their hats, bags or clothes, is a tag with their name and a barcode. A woman scans the barcode as they bring their filled bag to the crate to record how many bags they filled, and helps make sure that the apples are not bruised when they are emptied into the crate. The workers are paid by the number of bags they fill, so when they are sure their barcode was scanned, they run back to the trees to start all over again.

Fortunately, apples stay ripe on the trees for a long time, giving the orchards and the workers time to finish. With the Mosaic class, we had the opportunity to go to an orchard towards the end of a work day to see how the picking was done. I was surprised at how quickly everyone moves, often running to the trucks to empty their satchels and then continue picking. There are no formal rules on how to pick the apple, only an unwritten rule to not get in anyone’s way. In order to get to the apples, the workers jump, climb the trees and move around tall, rickety wooden ladders. When they are done, they take their bag of apples to a parked truck with enormous wooden crates and empty them. Attached to their hats, bags or clothes, is a tag with their name and a barcode. A woman scans the barcode as they bring their filled bag to the crate to record how many bags they filled, and helps make sure that the apples are not bruised when they are emptied into the crate. The workers are paid by the number of bags they fill, so when they are sure their barcode was scanned, they run back to the trees to start all over again.

While picking apples is difficult, intense work, Pennsylvania is one of the most popular places for the workers to travel to, and there are many factors that draw workers there. These factors include simple reasoning such as the weather being agreeable during the apple season, and more complex reasoning, such as the services that are provided in Pennsylvania for migrant workers. Through the mosaic, the students were able to visit different organizations that provided different services to migrant workers, like daycare, food bank, legal assistance, help finding new, permanent jobs in the area. As a result, many of the workers have been going to Pennsylvania for many consecutive years. For example, Saúl has been going to Pennsylvania to work the apple season for nearly fifteen years. While he now lives permanently in Maryland, he continues traveling as a migrant worker to Pennsylvania between August and October of every year. According to Don Saúl and many of the other men I interviewed, picking apples in Pennsylvania is the best paid work along the East Coast. In addition to good pay, Pennsylvania state law requires that, “Any seasonal farm labor camp within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is required to hold a valid permit prior to occupancy of the camp.”[7] This required permitting of the camps is designed to ensure that the living spaces and facilities are safe, clean and adequate. Understandably, the quality and availability of living space and common facilities for the workers is a major pull factor for many migrant workers.

Circular Motion

When the apple season is completed, the cyclical route kicks up again, and the workers travel back to Florida. The time spent traveling or in transition between each geographic location is always very stressful and unpredictable for the workers. The day they leave depends on whether or not all the work is actually done at the orchard, when the boss has their paychecks ready, and how long it takes them to pack their things. I was at BB the day the workers were supposed to be receiving their checks, and the atmosphere was very tense. Everyone seemed to be waiting around or doing things to kill time like cleaning their kitchen stations or making sure every little thing was packed. Between each location on the circuit, travelling is the most unsettling aspect of the experience, and the days leading up to the next move are always nerve racking.