The state of Pennsylvania is the fourth largest apple producing state in the United States, producing roughly 11 million bushels or 440 million pounds of apples per year. This amounted to approximately 21,000 acres in 2010 and attributed about $700 million to the state’s ecomomy. Over the years, the number of orchards producing apples has fallen, accompanied by a simultaneous decrease in the number of acres per farm. However, due to innovations in the industry, the yield per acre has steadily increased.

Adams County is one of the primary apple producing counties in PA, and is well-known for its “fruit belt,” a four to six mile wide swatch of land extending through south-central Pennsylvania.

The Food Security Paradox

Food security is defined by the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Guide to Measuring Household Food Security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy, life. Food security includes at a minimum the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and an assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g., without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing or other coping strategies)” (Bickel, Nord, Price, Hamilton, & Cook 2000).

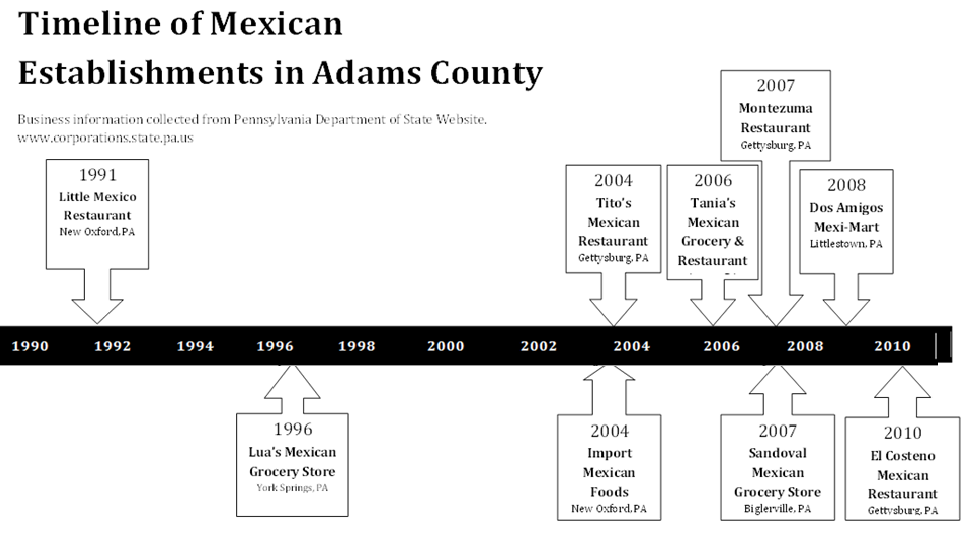

This timeline represents the increasing emergence of Mexican businesses in Adams County throughout the past twenty years (Figure 2). Establishment of new Mexican-oriented restaurants, groceries, and stores has occurred analogously to the increase in the Latino population in the past two decades. In a study on food access in Adams County, one Latina woman stated, “in our families, food is really one of the priorities” (Brown et al 2011;10). Cultural foods remain an important part of many migrant farm workers’ diets as well as the settled population. The presence and increasing population of Mexican food resources helps to continue this tradition in providing culturally-relevant foods. Acculturation and adoption of an “Americanized” diet can have detrimental effects on the health of Latinos. Less acculturated women eat more beans, fruit and vegetables, and eat less fat than women that have been acculturated (Cason et al 2006; 146). If these links do exist, Latinos in the county luckily have had increased access to Mexican foods over the last two decades due to the increase in Mexican food stores. In the words of one man,

“Years ago we used to eat only the things that were here- hamburgers, pizzas, roasted chicken, and all kinds of American food…Now 90% of the food that we eat is Mexican” (Cason et al 2003; 16).

Perhaps these stores have the ability to act as a safeguard to some extent in dietary acculturation and therefore improved long-term diet. This may be the case granted the cultural diet individuals are consuming is a healthy and well-rounded one. Ethnic foods appear to be important in not only preserving cultural tradition but also in maintaining a healthy diet. Some studies in Adams County also suggest that larger grocery stores are also playing an increasing role in providing Mexican foods,

“Ten years ago it was difficult to find tortillas, and now it’s easier to find almost any type of Mexican food at any big grocery store. Now we try to eat the food that we used to eat in our country” (Cason et al 2003; 16).

The establishment of new Mexican stores is reflective of community composition changes and the increased population of settled Latinos. Latinos are not only increasing their prevalence in Adams County population figures, school demographics and workforce, but also in the business sector. Such changes indicate and reinforce the permanence of the Latino population in this area and their contribution to the local economy. These stores also serve an important function for the migrant farmworker community (Jane Luceno).

Mapping Environmental Barriers to Food Security

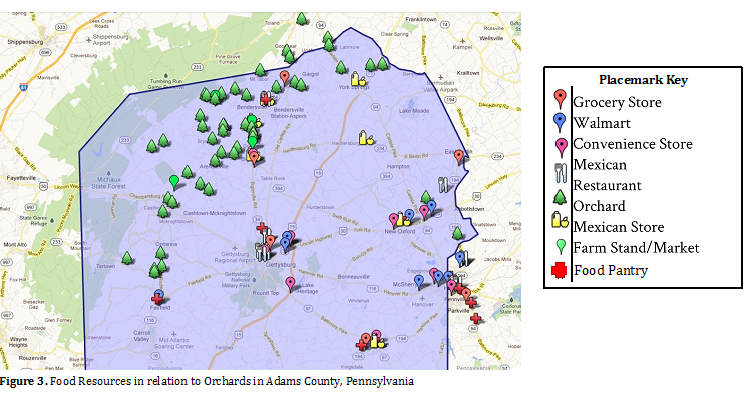

For many farm workers employment and home are tangled together as housing is provided by employers. Work for many migrant workers in Adams County is also connected to shelter and food, since many growers provide housing with kitchens on site for the workers, thus employment is not only a strictly monetary exchange. Orchards such as Bonnie Brae, even provide housing free of rent for its employees. The built environment of housing has influences of food security, particularly access to grocery stores within a relatively short distance. Both isolated living conditions and transportation can be a limiting factor in household and community food security (Cason et al 2003; 14-15, Cason et al 2004; 5). Mapping technology included in the Google Maps program was used to map the location of orchards, the home location of many migrant workers, in relation to food sources. This map was created with the Google Maps software, which was used to draw Adams County lines. Once these county lines were established, color and image coded placemarks were used to denote the different type of food stores throughout the county. A key was created to decode the associations of the different placemarks. There are a total of eight categories of placemarks, which include: orchard, grocery store, convenience store, Wal-Mart, Mexican restaurant, Mexican grocery store, farm stand/market, and food pantry. The map does not include other types of restaurants since the objective of the map is primarily to illustrate orchards in relation to food stores, food pantries, and Mexican food stores and restaurants, as the majority of migrant workers are Mexican (Borre 2011; 7). The map was compiled using information provided by Pathstone, an organization that provides services to the farmworker, rural community and low-income community. Pathstone provided information on the location of orchards in Adams County; these addresses are used by the organization to recruit and educate migrant farm workers about skill training and services available to them. This organization also provided the addresses of food pantries in the local area.

In order to analyze the relationship between transportation, access to amenities and location of housing the Walk Score program was utilized as part of this research. Walk Score is an online program that calculates the “walkability” of a particular address. This information can be useful in determining the influence and necessity for transportation for migrant farmworkers that live in housing within the orchards.

One of the most interesting things in the field of anthropology or sociology is an individuals’ ability to adapt to constant change when placed in situations that require them to do so. Whether it be changes in their societies and communities, their personal lives or in physical locations, people find ways to adjust their lifestyles according to the trials that they confront. Over the past three months I have been studying the routes taken by migrant farmworkers in the United States, and the ways that they have adapted their lives to always being on the move. Two of the workers I spoke to were able to provide me with a great deal of information, yet they each have very different experiences as migrant farmworkers in the United States.

The story of one woman, Marta, is very interesting, as it provided information on a migrant farmworker’s experience, the woman’s experience and a mother’s experience. Marta is a young woman from Veracruz, Mexico, who has been in the United States for almost ten years. She crossed the border with her younger sister in a large group of people. Marta and her sister travelled together for a few years with a small group of other women and some men, following the migratory route from Florida to New Jersey to Pennsylvania. Eventually they both got married and started travelling with their husbands. Marta’s sister lives permanently in Wisconsin and travels from time to time to other places for work. Marta and her husband have decided to continue following the East Coast route. They have two young children, a girl named Kelly who is almost five years old and a little boy name Jose Manuel who is 7 months old. Marta mentioned that when her children start to get older she would like to make a more permanent move so that the constant moves will not have negative impact on their schooling and education, but she does not know where yet.

Don Saúl’s story was just as interesting and informative as Marta’s. He is an elderly man from San Salvador, El Salvador, and has traveled back and forth to the United States multiple times since his early 20’s. What makes Don Saúl’s story interesting is that while he has spent the majority of his time in the United States as a migrant farm worker, he has also spent time at a permanent residence in Maryland where he works odd jobs while he is not travelling. Don Saúl is in the U.S. alone, without family, but has two adult daughters that he sends money to in El Salvador.

While Don Saúl is undocumented, he was very open about his history and his experiences crossing the border. The first time he came to the U.S. he paid a coyote to help him cross the border, but since then he has always crossed alone or with smaller groups of men using his memory as a guide. Don Saúl’s journey to cross the border is much more treacherous than a Mexican immigrant’s journey, because he must travel into, through and out of Guatemala, and then travel through Mexico to one of the border towns to prepare for crossing into the United States. Don Saúl spoke about an underground bus system set up along the Guatemalan-Mexican border to take people through Mexico. The “convis” or busses are normally packed with Guatemalan, Salvadoran and other Central American immigrants in a trip that lasts almost two days. This journey to simply get to the Mexico-U.S. border can last anywhere from five days to a few months, depending on weather, transportation, how many people are travelling, and run-ins with authorities. Once in the United States, Don Saúl takes a train or bus to his destination.

For the first few years upon arriving in the United States, Don Saúl worked mainly in California, but decided to move to the east coast when he heard that the pay was better. Like many new migrant workers, he began working in Florida and slowly started the routine of travelling with the other single men north when the seasons changed. When asked if workers share each other information on where to go for work, Don Saúl chuckled and continued to explain that unless you have family members who are already established, or are travelling with other men, it is difficult to get advice from other workers on where to go or which orchards to work for or avoid. One would think that they would want to help each other; however there is a level of competition that is only increasing as more migrant workers come to the U.S. Thus, while some information is passed, individual preferences are developed by individual experience.

Eventually Don Saúl developed a preferred route on the geographic circuit based on his own preferences as to camps or farms he was comfortable working, where the pay was better, and which seasons were going to be good for picking or not. After a few years travelling the route from Florida to New Jersey to Pennsylvania, Don Saúl decided that settling in one place would be easier and more economical for him than travelling constantly. He was discouraged from his original routine of travelling for work when there was a period of consecutive bad seasons for the farmworkers. He explained that because most of the work picking is paid by quantity, when there is a bad season, he would get paid less. Now, Don Saúl lives in Maryland working construction jobs, window washing, and as a janitor. The only time of the year that he picks fruit is during the apple season, because it is the best paid job at that time of the year. During the apple season he travels to Pennsylvania with other men that live near him, and then they return at the end of October when the season is over.

Don Saúl has been living as a migrant farm worker and undocumented immigrant for many years, and while each individual experience is incredibly different, details from his story do resonate in the stories of many other Latino migrant farmworkers (Jane Luceno).

Apples and Immigration in the United States

Globalization and international competition in agricultural commodity markets, along with lack of appropriate government support, means that the apple growers of Adams County struggle to lower production costs while consistently providing a high-quality product for the competitive market. American consumers no longer remember the natural, blemished state of fruit or the small family orchards that flourished across the country. Instead, consumers have become accustomed to the lustrous red strains of apples that evolved as the product of competition between Northeast and West Coast producers “setting the standards for ‘pretty’ apples in new and larger supermarkets” (Yoder, 2008, p. 86). We now demand these beautiful, shiny red apples, caught on the same path of temptation that led Eve and Snow White down precarious paths. And so the American apple industry finds itself on an increasingly unknown and unstable path as well. By losing sight of the roots of the original apple tree, we have lost a sense of our own roots as well. The apple is a non-native species of fruit that was brought to the shores of America, only to develop into thousands of individual varieties with different strengths and weaknesses. Some grew wild and pioneered westwards, while others were lovingly tended to and cultivated until they grew into the unique varieties of apple beloved by all. In many ways, the apple embodies ideals and values associated with the positive aspects of the United States.

Yet the true irony of the situation is that a strong nativist sentiment prevails in many areas of the country that rely on migrant agricultural workers to keep industries and economies functioning. To demand that a non-native fruit be grown and provided at a low cost while simultaneously refusing to have “non-native” people doing this grueling work is nonsensical.

Public discourse simultaneously refers to national security as “securing America’s borders” and as the ability to produce our own food. The harsh reality is that globalization has rendered both of these things impossible. A globalized industrial agriculture system means that America cannot produce its own food without the help of a massive migrant labor workforce that comes, in the case of apples, primarily from Mexico. Likewise, a global exchange of culture and ideas has redefined borders and changed what it means to be American, Hispanic, Latin@, or “white.”

Americans must ultimately acknowledge these changes and come to grips with the globalized nature of modern societies. Americans must recognize that the hands of migrant laborers from Mexico pick the apples in Adams County, Pennsylvania that are baked in pies and eaten across the country at Thanksgiving. We must look beyond images and concepts society has come to associate with apples that are stereotypically “American” and are closely linked to patriotism and white, middle class life: these images hide the real face of the American apple, and that is the face of migrant labor. Embedded in Thoreau’s assertion that strong parallels can be drawn between the history of man and the history of the apple is the recollection of the Sour Crab apple, the native species of North America. Just like we never speak of the reality of the indigenous apple, we rarely acknowledge the indigenous race of North America, similarly evolved into thousands of unique yet equally beautiful varieties (Rachel Gilbert).