Padua: A Northern City in Conflict

Bienvenuti! Today’s blog will be starring Northern Italy’s oldest city: Padua, or as it is known in Italian: Padova. Coincidentally enough, as we are in Italy studying migration, likewise it is said that Padua was founded by the prince of Troy fleeing the loss of his home (some might call him a refugee), ultimately growing into one of the richest cities in the Roman Empire known as Patavium. Then again during the scourge of the Huns, refugees fleeing Padua found safety in the wetlands to the east that would ultimately become the famous city of Venice. Therefore it is interesting to note that while today some 30% of the citizens of Padua support Lega Nord, the very conservative anti-immigration political party in Italy, the city itself has a very rich history of migration and refugees. To further elaborate on the political climate, Veneto the province that Padua is a part of, Lega Nord received around 35% in 2014 while in Emilia-Romagna the province of Bologna and neighbor to Veneto, only had 19.4%. This was further shown by the experience that some of our group had while listening to a very intense taxi driver express very anti-immigration sentiments on the way to our destination. To paraphrase: ’The invasion of the immigrants is due to a conspiracy supported by the U.S. and Italian left-wing parties.’ However all in all, while this rich history and brief background into the political climate of Padua may be interesting, it is time to discuss what we did today.

Our goals for the day were to first meet with an advanced english language course for masters level students studying political science and international relations and just have conversations with university students about their own perceptions of migration, whether or not they had academic knowledge.

Personally, I had the pleasure of speaking with two students with different migration stories which they willingly discussed. The former, was a Syrian Human Rights lawyer with a focus on violence against women, who was in Padua on fellowship for six months. The most striking points that this student made were her takes on Europe’s methods of approaching the migration “problem” and her own personal feelings towards the position of her countrymen as refugees.“I don’t want to be here, instead of worrying about refugees in Europe, fix the problem in Syria so that I can go home.” It was at this point that I reflected greatly on the real reaction by the western world in regards to Syria and the refugee crisis. In addition to these remarks the passion and the desperation that was expressed by this intelligent young woman showed the struggle that many in her shoes face. In the media the western world sees words such as “invasion” and “flooding” of migrants into Europe, worried that they’re going to suck away at their social security systems and cause a burden on their economies. However, not only is that wrong, most recently Sweden’s GDP increase for 2015was higher than expected, due in part to migrants. For the most part, these people who escaping war, violence, and persecution want to return to rebuild and live in their homeland.

The other student in our group was a man whom had migrated from Calabria, a city in the south of to Padua for an education, and like most other Italians following this trend called himself a migrant to the north, an interesting concept for a country that has been unified for over a hundred years yet still holds very regionalized opinions about their fellow citizens. This was followed by an intense discussion of the “Caporalati” who are migrants (usually illegal) that have been manipulated or coerced into forced labor in the fields working for usually only 15 euros a day. Much of this illegal work is controlled by the Camorra and is used for their own profit. The most interesting aspect of this trend is the government’s inability to fix this trend even though they have put in legislation that has no effect because of the control over the local governments that the Camorra has. While this breaking into groups was an amazing experience and the first time that we had the ability to understand what our peers in Italy were thinking of these same topics that we’re covering, it was only the first activity that we did in a long day’s worth of immersion and interviews in Padua. That afternoon we engaged in a languaging workshop.

The concept alone of a “languaging workshop” is progressive. In it, the participants are encouraged to use language at their whim, to seamlessly meld multiple tongues into a textured conversation, accessible to many because of its multilinguality. The participants were from diverse backgrounds and each held personal motivations for practicing english. The group included Egi Cenolli, the female president of the Council of Foreigners, two elderly men, one of whom was a retired middle school head and the other an activist in Razzimo Stop. There was also Debre, a migrant from Ghana and Erica who works for Save the Children and an organization that promotes anti-racism through sports. Leading the group was Francesca Helm who is also a migrant, however, her journey was from London to Italy. Having spent a major portion of her life in Italy she is bilingual and directs the workshop with ease. After introducing the class, she explains that the freedom of language in the class creates a sense of solidarity between people. A consistent theme we’ve found during the mosaic is the unifying, and also dividing, power of language. Nonetheless in this setting the participants used languages to relate and share with one another.

After explaining the purpose of our program, Maurizio who is a part of Razzismo Stop launched into a thorough yet concise summary of migration policy and competing ideologies in Italy. He began by addressing how the geographical placement of Italy has always made it a transit nation. Migrant numbers did not rise though until the influx of Albanians in the early 1990s which in part he attributes to the romanticized images of Italy on television. The second wave of migrants were those searching for work. Most recently, the third wave of people are evacuating nations racked by war and prosecution. While these migrants are fleeing from violence often perpetrated by other citizens of their country, “we are to blame,” he said, because “we the Europeans, U.S., and Russia start and incite the wars.” The activist continued. He explained how politicians use information to polarize people, get votes, and create doubts. He identified the mayor of Padua’s position: ‘the solution was to help migrants in their home nation first before they come to Europe.’ This led him to bring up what had been happening contemporaneously the day before, Greece and Macedonia closed the border and the refugees in Calais, France were evicted.

The microphone then passed to Debrey (on the left with Dickinson student Isaiah Gibson) , who came in a little late but made sure to go around and shake each of our hands. Previously a teacher in Ghana, he made his way across Africa, stopping in Niger to earn money teaching. By 2006 he was in Libya, dangerously close to the rebel base. To escape, he travelled to Lampedusa, eventually reaching Padua. Two years ago he was accepted into the Casa de Don Gallo home for migrants. The building, occupied by squatters 2 years ago, houses 60-85 migrants, mostly men. They live in what was once bank offices without running water or electricity; the commune had recently cut off the electricity.. Many of the inhabitants hold seasonal jobs, some have none. Debrey told us of how it became crucial for the men to work together, pooling skills and creativity in generating income. In the outdoor space, they fix bicycles and do small carpenter jobs. The city council was of little help, for while they listened to the migrants complaints, they never took any action to help. When asked how come people still come to Italy despite knowing, how difficult life here is for migrants, Debrey had a simple response: no one wants to live like their parents so the only option they see is to search elsewhere for new and better life chances.

Erica spoke next. She began by saying, “my life is a story of immigration” since she was born in Palermo, Sicily. Her talk was focused on the anti-racism sports organization. In addition to providing athletic outlets for the players, the group also concerned themselves with the players’ quality of life. The organization worked towards changing the rules regarding players registered abroad. Formerly barred from them registering again in Italy, these individuals can now play in Italy too. Erica works for Save the Children that also provides beneficial services for the migrants. One service they provide is a the safe space for children both with and without their parents. Another topic Erica also discussed was her dislike for the term “integrate;” she believed it insinuated that someone is integrating into another culture, as though leaving their previous one behind. She would prefer a meeting in the middle or a more hybrid meld of the two cultures involved. Interestingly, she said she would prefer to use the phrase “melting pot,” a term once popular in the US that has now fallen out of favor. The quality of melting pots, boiling down all the components into one homogenous substance leaves no room for individuality. Social scientists today prefer the analogy of a tossed salad in which all the unique parts work together to make the whole.

To close the panel, Egi Cenolli spoke about the Council of Foreigners. The main issue was the failure of the city council to facilitate elections since their last ones in 2011 and thus, foreigners can not vote or have a voice. During their prime, the council had been working towards achieving voting rights for all immigrants. Denied the opportunity to speak with the mayor about holding elections, the council of foreigners is at a standstill. They can sit in on city meetings but can do nothing. This corroborates Debrey’s statement about the ineffectual and inactive behavior of the local government.

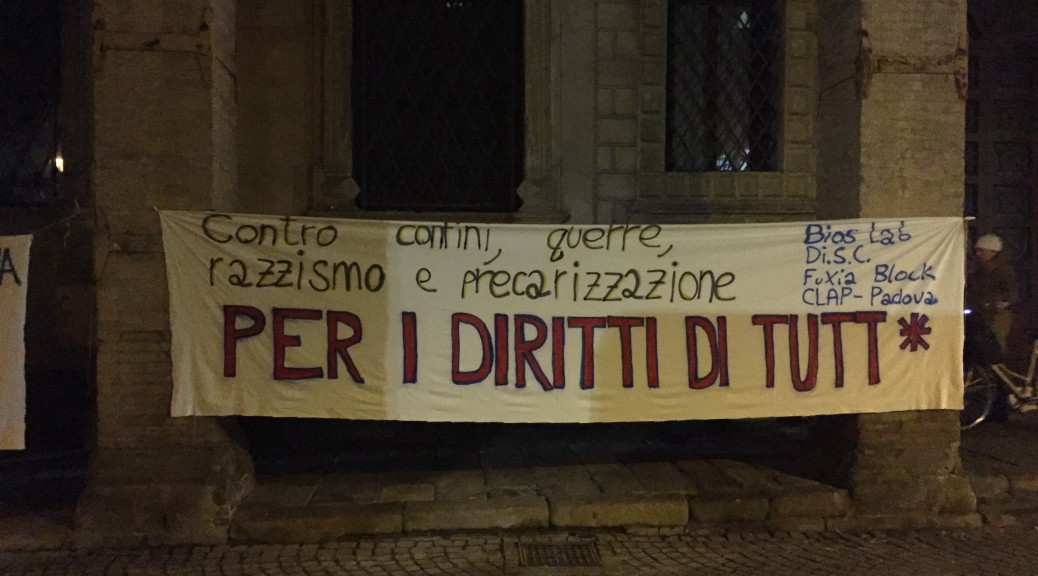

The panel came to an end around 6:30pm because a number of its participants wanted to attend a protest taking place in the main square. In light of Padova’s political reputation, this protest for migrants rights was bound to be controversial. It was already dark but the square was lit by street and traffic lights. There were people milling about in groups throughout the square with most congregated around a large stone tomb. Holding it up are four large pillars. The two in front of which the crowd gathered had been wrapped in orange life vests. With the artificial light in the square, these vests glowed eerily as though on fire. On the vests there were stickers reading, “#overthefortress”.

The rejection of “Fortress Europe” was a persistent theme throughout the protest. The speakers discussed it, picketers called for its end. University students, older couples and everyone in between could be seen at the protest. A number of young people carried signs, most of which were in Italian; one in english read “Open the Borders”. Two large sheets hung on a nearby building. On these, they stated this was a demonstration to gain citizenship rights for all. A young woman explained this over a microphone in the center of the congregated people. She spoke sternly but remained composed. Shortly after, a young black man from Gambia was given the microphone, despite the hesitation expressed by one man orchestrating the demonstration. As soon as he began talking we all were entranced. Passionate, angry, in pain, each accusation and story became increasingly powerful. He spoke about his escape from persecution, and who his brother was unable to do so here and thus was sent back and immediately killed in the airport when he arrived. Pleading, he asked how Italy could let that happen? How could they let so many people die at sea? How could they deny aid to genuinely desperate people? Eventually the skeptical man came over and passed the microphone to someone else. Our mosaic dispersed a bit after that, some going to talk with the Gambian man, others to talk more with Debrey, and Ingrid and me to speak with Matty. Probably in his early 20s, Matty is a friend of Debrey’s who also lives in the Casa Don Gallo.

He is from Mali so we spoke French. Our conversation was casual but after talking to us about his position on the immigrant football team Erica organizes, he told us about his journey to Padova. First leaving Mali to follow his mentor in mechanics to Libya, Matty eventually had to separate from him and Libya itself due to the war that broke out in 2011. Traveling first to Lampedusa, he then made his way north. Matty’s gentle demeanor and casual tone gave the impression we were having a chat about yesterday’s Arsenal match. The juxtaposition of his composure and the passion of the Gambian speaker was striking. I am continuously impressed by migrants’ resilience even after such tragedy and trauma.

-Ralph Humiston and Paige Hamilton