February 21, 2016

“Forget the word ciao.” This was the advice that Professoressa Clarissa Pagni gave us upon our arrival at the Dickinson Center in Bologna on Monday. The first, and often only, Italian word that people know is ‘ciao,’ but as Professor Pagni told us during our orientation, what many people don’t realize is that this is the informal way to say hello and should only be used when greeting your peers or children or those you know well. In most cases, the formal greetings ‘buon giorno’ (good day) and ‘buona sera’ (good evening) are more appropriate and are a sign of respect for people you do not know.

After our orientation, we enjoyed a comprehensive lecture from Professoressa Michela Ceccorulli, a professor at the University of Bologna and the Forum on the Problems of Peace and War (Florence) who also teaches at the Dickinson Center for European Studies in Bologna. Her talk, “The European Union and Migration: from Schengen to the Ongoing Refugee Crises,” outlined the many laws, policies, and agencies involved with migration.

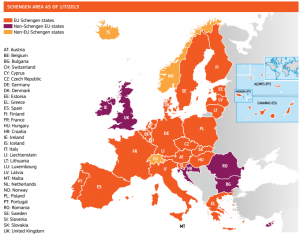

She began with an overview of the European Union, which consists of 28 countries in Europe and the Schengen Area which includes many but not all members of the European Union as well as some non EU members. Under the Schengen Agreement of 1985, citizens of Schengen member states are allowed to move across the internal borders of the Schengen Area without being subjected to border checks. EU members which join the Schengen Area further enhance the rights of their citizens who are already guaranteed the right to work, travel, or live freely in all other European Union countries.

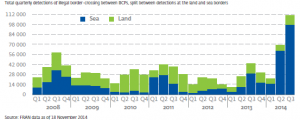

Understanding of the Schengen Agreement and the policies within the European Union is crucial for discussions about migration. Because of the lack of internal border checks within the Schengen Area, many migrants want to arrive in a Schengen state so that they can then travel within this area to work and live. It they are able to get to Italy or Greece or Spain, they then can freely move through or stay in other Schengen countries. Because of on-going economic and political crises in Syria, Libya, and Tunisia (and in other countries in Africa and the Middle East), a large number of migrants are crossing the Mediterranean sea. Currently, Italy and Greece are experiencing disproportionately high numbers of incoming migrants compared to the rest of the countries in the EU. Professoressa Ceccorulli included the following graphs in her lecture which show the increasing numbers of sea crossings through the central Mediterranean to get to EU borders.

In order to alleviate pressure from the increasing numbers of migrants arriving at the EU’s borders, the EU introduced a border control agency called FRONTEX in 2005. It replaced Operation Mare Nostrum, an Italian governmental initiative which was dedicated to searching and rescuing boats of migrants in the Mediterranean. Policies and agencies in the EU today are becoming more focused on deterrence rather than humanitarianism.

As she wrapped up the lecture, Professoressa Ceccorulli left us with some open questions about migration that are strongly debated today and that we hope to answer through our research in this mosaic: is there a link between migration and terrorism? Should migrants be integrated into the EU countries and if so, how? Can the EU use migration as a solution to its aging and changing population? And most importantly, is the refugee crisis and the break up of the Schengen Area a threat to the EU?

Following the lecture that provided a macro overview, we learned more about migration from a grass-roots, micro, humanitarian perspective through an interview with Nago Ka, a Senegalese immigrant who lives in Italy. Today he works as a translator and interpreter for newly arrived migrants, especially unaccompanied minors, who are applying for asylum in Italy. One of the many poignant parts of this interview was when he shared with us that he does not have a TV or a radio because he “wants to think and to open the pathway against one dimensional thinking.” Unfortunately, the media today often portrays stories in a biased and linear way and gets readers and watchers to think too unidimensionally (Maddie).

Meeting Nago Ka

He stood outside the Dickinson Center gates on via Masala in Bologna, Italy. He was well dressed, which communicated to me that he had established himself in Italy. Nago was an older man with graying edges to his hair. He waited patiently at the gates to be let inside the building. As I approached him he began to smile at me, and as a natural response, I smiled back at him. I was extremely excited because it was our first full day in Italy and I had been hearing about him since the beginning of the semester. My professors had told me that Nago worked as a translator for migrants seeking asylum in Italy. Additionally, they told me that Nago works as a community activist for migrants and has played an instrumental role in helping immigrants establish safe spaces and cultural institutions to help create a better migrant experience in Italy.

He waked into the Dickinson Center with his hand cocked for a handshake and said “Buona sera. I’m Nago,” He had a firm handshake and he looked me in my eyes. I held his hand tightly and concentrated on looking him in his eyes to express my respect and appreciation for him visiting. Nago strolled confidentially like a person with great purpose. I could tell he was happy to be there and I knew I was about to learn a lot. Nago told me that he didn’t speak English but told me everything had been going well that day. As I led him to the lobby of the Dickinson center where he was met by Professor Borges and Professor Marini-Maio his smile grew even larger as he hugged the two people he was familiar with and they began to discuss the project and what they had planned for today. I focused on providing good hospitality by offering him drinks and snacks. This was extremely important to me because there was a language barrier between us and I wanted to make him as comfortable as possible. However, I realized that he had already made himself comfortable. He was open to everything and told Professor Marini-Maio he had no problem being recorded, speaking in Italian, getting mic’ed up, etc. I was relieved and no longer felt nervous about the interview.

During the interview Nago captured my intellectual spirit several moments, especially when he said, “I don’t have a TV or radio because I just want to think.” When he said this I thought about how much social media, politics, and blogs attempt to undermine and influence our thoughts to support a certain political party. In a way, it seems as if the people who are in control of the media are trying to program our minds to be monolithic and to accept the news stories that they create. If we allow ourselves to fall into this way of thinking then we will lose our ability to analyze things in a critical manner and from a holistic point of view. It is extremely crucial that we, as citizens, are able to think for ourselves because it allows us to support or protest issues from our own measures of morality. If we were able to achieve this, the world would not be segregated into right and left wing political parties.

Nago’s knowledge on the ways the media and politics affected the identities of migrant communities motivated him to dedicate his time to helping new migrants. He said that he stressed the importance of knowing how to speak the Italian language well to these young African migrants. He said that knowing the language would afford them the respect of the Italian people. This reminded me of how young black men and women are viewed in America as uneducated and inarticulate if they don’t speak proper English. Nago referred to himself as a warrior who has been working to recreate the narrative for African migrants in Italy. He characterized the thought process of many Italians who thought of Africans in a negative light as one-dimensional. Italians who over generalize these African migrants as being thieves, lazy, and criminals miss out on meeting extraordinary people like Nago. However, Nago also acknowledged that African migrants play a role in the existence of these stereotypes. Nago cautioned new migrants to not do bad things like stealing, no matter how desperate they are.

Nago through his work as translator, community activist, and educator continues to debunk the stereotypes about African migrants in Italy. Nago is a man of wisdom, conviction, and great moral character. Nago is a man whose hard work continues to make a positive impact on his peers who are African migrants, Muslims, and the youth. Nago is the type of man that one wishes to have as a father, uncle, and/or friend (Isaiah)

The purpose of this mosaic is to learn as much of the full story of migration as possible. We spent one month before we arrived in Italy, reading and writing about the history, perceptions, and reasons behind migration. I believe that I can speak for my classmates when I say that the amount of work we had caused many late nights in the library, but it expanded the depth and breadth of our knowledge of migration in ways that we could never have thought possible in one month.

As our mosaic begins working in the field in Italy, we are continuing to open our own pathways against one dimensional thinking, whether we are learning about the nuances of Italian greetings or the complex components of migration. We hope that this blog will reflect the expansion of our knowledge of migration and that you will join us in shedding the one dimensional thinking that surrounds us (Maddie and Isaiah).