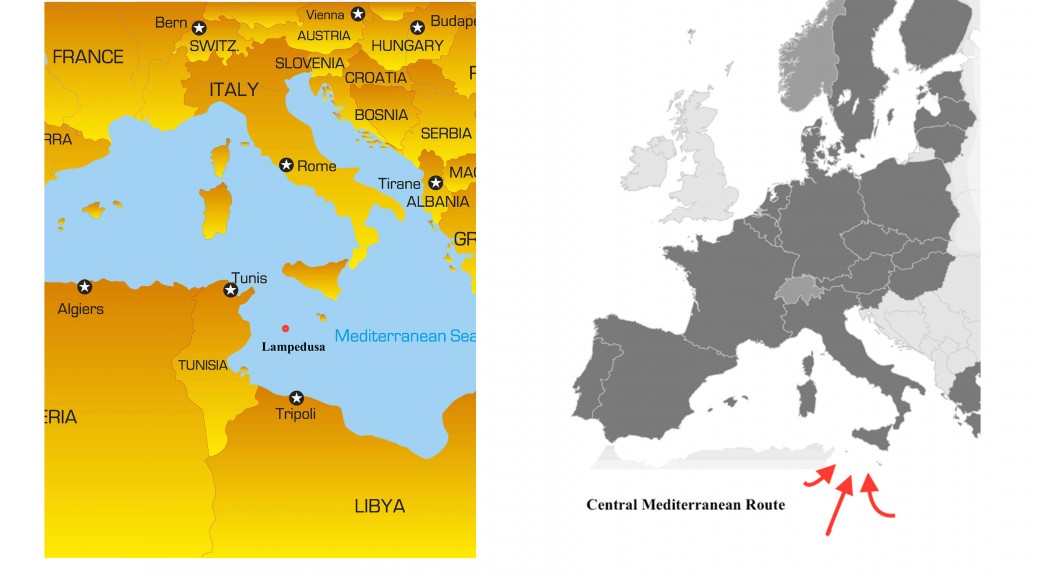

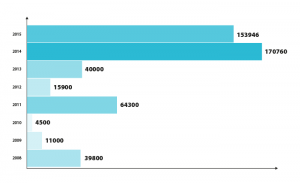

Our journey to Lampedusa started with an early morning flight from Palermo. Lampedusa’s close proximity to North Africa and its southern location has made it the focus of a huge topic of debate within the European Union’s dialogue on migration and border control. Following Spain’s strong focus on monitoring the strait of Gibraltar and migration from Morocco in the early 2000s, migratory trends shifted from there to Lampedusa and increased greatly following the Arab Spring uprisings in both Tunisia and Libya. After the numbers of those using this central Mediterranean migratory route dropped from 39,800 in 2008 to 11,000 arrivals in 2009, the number of illegal arrivals spiked in 2011 with 64,300 illegal arrivals entering Lampedusa as seen in the below graph.

Yearly illegal arrivals using Central Mediterranean Route

*Please note that FRONTEX database in 2014 began combining the arrivals using this central mediterranean route with the Apulia and Calabria route which explains the huge increase in 2014.

Global attention dramatically focused on the “migrant crisis” evolving in Lampedusa, especially after the 2013 tragedy when at least 103 migrants lost their lives when the boat carrying them capsized making headlines throughout Europe. The tragedy of human loss attracted the attention of public and governmental figures who then visited the island, including Pope Francis. Even though the number of arrivals in Lampedusa has decreased since 2014, news reports still talk of the invasion of migrants and the role of Lampedusa as a major border – indeed – frontier of southern Europe. A large reception center on the island that processes the new arrivals before they’re dispersed throughout Italy is on one side of the island, while the tourist attraction and center of town is on the other side. While in the last few years the migrant situation in Lampedusa has been the focus of many international news reports and documentary and feature film productions, it is also still famous for its beautiful beaches and the Isola dei Conigli (Rabbit Island), a wildlife preserve and one of the last places in the Mediterranean for turtles to lay their eggs.

As we flew over the Mediterranean and saw the shores of Lampedusa, I couldn’t help but think about all of the people who have crossed those waters and those who lost their lives in them. Even from high above, I could see the whitecaps and the violence of the waves. Our first interaction with the present migrant situation on Lampedusa started with our group sharing the plane ride from Palermo with a large unit of the Italian Police travelling to the island for their week-long shift in the reception center. These officers were responsible for registering incoming migrants into the FRONTEX system. In the plane there was also a customs officer whose job consists of appraising the boats and seizing them if they are abandoned. Both the migrants and the boats that carry them, are ‘technically’ considered goods entering the European Union. It was interesting to hear the personal opinions of a variety of people in regards to the situation in Lampedusa, particularly among a few of the officers. For instance one of the policemen stated that it was just his job, and that as for the migrants, there was nowhere else for them to go so even if they did want to try to escape, “it’s a small island with nowhere to go.”

Having spent the month prior to our arrival in Italy immersing ourselves in the relevant literature and filmography, such as the recently released documentary Fuocoammare and Terra Firma produced earlier in 2011 and Mare Chiuso, surrounding the political, cultural and emergency status of the Island of Lampedusa, there was a common uneasiness among our group while on the plane and then again at the airport, a feeling much more like one is entering a restricted zone rather than a beautiful Sicilian island in the middle of the Mediterranean. Additionally, once we stepped off the plane we were given a taste of the strong winds that hit the small island in the center of that sea, with strong gusts that whip up the ocean waves and as well as hats off people’s heads.. It certainly made us reflect on how many migrants faced similar, if not much more severe winds on the open sea while they made the dangerous voyage to Lampedusa.

As I was riding in the cab I was expecting to see the booming tourism business, native Lampedusian restaurants, and thousands of tourists. However we had come to the island during the winter season, so instead it seemed very desolate and quiet with various stores closed. However, this was not a bad thing, it allowed me to focus on my research and see Lampedusa in its off-season.

At first, the streets seemed empty though I felt the carabinieri staring at me, as well as the locals of Lampedusa and African migrants. Then at approximately 1 pm I began to see large groups of African people start to populate the large plazas throughout the downtown of Lampedusa. I had taken a guess that they were released from the reception centers nearby to get some fresh air. All of these migrants were men and they all were dressed the same with a black and blue jacket, black sweat pants, and they all wore green or yellow sandals. When I saw these people dressed in this attire I thought of the first African man I saw with the leather jacket. I had deduced that clothing could possibly be an indicator of how long these migrants had been on the Island. I also noticed that the African men who wore different clothes moved in smaller groups or alone and they interacted more with the Lampedusans. On the other hand, the migrants that I thought were new sat on the benches in complete silence.

As I observed the only thing that came to mind was the question: what are their dreams? I began to place things into perspective and look at my own clothing. I thought that this could be a reason why so many people are watching me. I was wearing a heavy black jacket that had brown fur in the inside of the hood, blue jeans, blue sneakers, and a black and white sox baseball cap. My thought stream was interrupted when I watched the police and carabinieri do their rounds in the neighborhood and I immediately thought of an outdoor prison. I began to investigate this thought further as I compared the structure and conditions of a prison: the migrants were on an isolated island from the mainland of Italy, they did not have money or the opportunity to have a job, the police monitored their movements, and all they could do was to think. Maybe a prison was too extreme, having this time to think in peace and silence might have been therapeutic for these migrants who may have just survived the traumatic act of traveling through the sea.

Since we all scattered for lunch (we wanted to explore in pairs so that we were more likely to interact with locals), we later shared our various experiences. One of our classmates, Maddie, recounts her interesting experience with locals as follows:

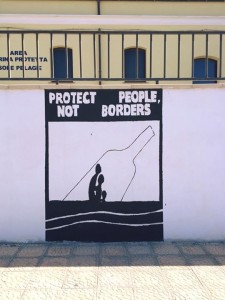

“As we continued to walk we passed a painting on a wall of a marine protection building that said “Protect people, not borders.”

I had seen and heard this phrase before, but seeing it in Lampedusa where it is so relevant was particularly impactful. Not far after that mural, we passed a dirt lot that had 10 wooden boats in it along with other vehicles. Many of the boats had what I thought was Arabic writing and designs on them and letter and number markings which were obviously not part of the original design. We realized that these are some of the boats that the migrants must have come on to Lampedusa. We walked again to the water and there was a fisherman there cleaning off his hands. He said hello and we asked him about the boats that were in the lot. He told us that they were boats that migrants had come on and that the letters determined who had found them (Coast Guard, Guard of Finance, etc). Eventually we were able to ask if he ever encounters the boats while he is fishing and he told us that he does all the time. When he does see a boat he said that he gives them water and tells them what their coordinates, perhaps so that they can call for a proper rescue. As we asked him (and other locals) more about migration, he seemed to get more distant. I wonder if this is because they are wary of journalists, if it is because they have to discuss it so often, or if it is a subject that they prefer not to discuss, or if it could be a combination of all of those. As we walked back into the center of the town, we saw a man who we think must have been an immigrant because of the similar jacket and pants he was wearing being interviewed by a journalist. This just confirmed that the media is constantly present on the island.”