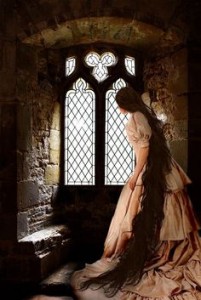

Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” is a poem that tells the story of a cursed lady imprisoned in a tower on the island of Shalott near the city of Camelot. Through her curse, she is unable to look outside of her window into the real world. As a result, she is forced to live a life where she weaves a tapestry all day every day unable to see the world except through the reflection of her mirror. Although the tale seems to focus on an unattainable love, a much more Victorian understanding is unraveled when one focuses on the role of the lady of Shallot.

No time hath she to sport and play:

A charmed web she weaves alway.

A curse is on her, if she stay

Her weaving, either night or day,

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be;

Therefore she weaveth steadily,

Therefore no other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

In the first stanza of the second part of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” a woman is introduced, described as unattainable, composed, and dedicated to her womanly tasks – all of which an ideal Victorian woman should embody. She is described as being “cursed.” However, the reason for her curse is unknown to readers, as the woman herself does not even known the reason. Despite the passing of knights on horseback, priests, etc., the lady “still delights [in her web] / To weave the mirror’s magic sights,” showing how dedicated she is to fulfilling her tasks (which is weaving the beautiful world around her).

Despite the “perfection” to which the lady seems to embody, her downfall becomes evident when a man by the name of Sir Lancelot passes by her tower. Depicted as the most dashing and chivalrous of all knights, the lady of Shallot cannot help but look away from her mirror to see the image of the great knight from outside of her window.

She left the web, she left the loom

She made three paces thro’ the room

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Up until this point in the poem, the lady of Shallot is considered the ideal woman because she is isolated from society’s temptations, making her a very innocent individual. However, when Lancelot comes to the scene, she is no longer the innocent woman she once was because she is tempted by her desire to see the real Lancelot – that is, Lancelot from outside of her window, not from the reflection in her mirror. From this point forward, she exits her tower, entering a world where evil lurks.

This particular poem breathes domesticity. While men are constantly passing the tower doing “manly” things (most likely), the lady of Shallot is confined to her tower, where she is subdued with tasks such as “weaving a web.” As a result of her unawareness of the outside world, the lady leads an ideal life (from a Victorian standpoint) because she is unaffected by society’s temptations. However, the instance that she decides to look away from her mirror outside into the real world, she knows what is going to happen: death.

Tennyson’s poem, “The Lady of Shallot,” seems to function as an admonition. He introduces an interesting story about a woman and her newfound infatuation for the great Sir Lancelot to write that, when women escape their domestic lifestyle comprised of “womanly” tasks, the ultimate conclusion is death.

icate the object being bartered which in this case is sex and everything ‘unholy’ that comes with being impure. I also think that because Rossetti would have been biased against men especially because of her bitterness towards not being a part of her brother’s pre-Raphaelite brotherhood and so she might have used the evil, demonic goblins to represent men and their tendencies. Another hint would be Laura exchanging a lock of her hair for fruit from the goblin men. In class we talked about how lovers would carry around a lock of each other’s hair-representing Laura having a romantic connection or affiliation to the goblins. I found this really interesting so I decided to look into hair in the Victorian era and what it meant in society and apparently hair also represented women’s sexuality and empowerment because the longer your hair was the more fertile you were so by the Goblins taking a lock of Laura’s hair could mean taking away a part of her womanhood- i.e. virginity and purity or taking away her wholesomeness an

icate the object being bartered which in this case is sex and everything ‘unholy’ that comes with being impure. I also think that because Rossetti would have been biased against men especially because of her bitterness towards not being a part of her brother’s pre-Raphaelite brotherhood and so she might have used the evil, demonic goblins to represent men and their tendencies. Another hint would be Laura exchanging a lock of her hair for fruit from the goblin men. In class we talked about how lovers would carry around a lock of each other’s hair-representing Laura having a romantic connection or affiliation to the goblins. I found this really interesting so I decided to look into hair in the Victorian era and what it meant in society and apparently hair also represented women’s sexuality and empowerment because the longer your hair was the more fertile you were so by the Goblins taking a lock of Laura’s hair could mean taking away a part of her womanhood- i.e. virginity and purity or taking away her wholesomeness an