Thanks to Tony Moore–Dickinson staff writer and editor–for several great news stories about the Mosaic:

Mosaic Classes:

http://www.dickinson.edu/news-and-events/publications/dickinson-magazine/online-features/2012-13/Mosaic-Afield/

Crabs and Ooker on the Bay:

http://www.dickinson.edu/news-and-events/publications/dickinson-magazine/online-features/2012-13/Crabbing-with-Ooker/

Fossils in the Quarry:

http://www.dickinson.edu/news-and-events/publications/dickinson-magazine/online-features/2012-13/King-Phillip-Came-Over-for-Good-Soup/

Hawks and Eagles on the Ridge:

http://www.dickinson.edu/news-and-events/publications/dickinson-magazine/online-features/2012-13/Raptor-Shadows-on-the-Sleeping-Blue-Lady/

and here is how it all started:

http://www.dickinson.edu/uploadedFiles/centers/community_studies/content/Natural

20History20Sustainability20Mosaic[1].pdf

Students collect butterflies and other insects outside of the new CSE (Center for Sustainability Education) offices at Dickinson College, under the guidance of Prof. Gene Wingert

Writing About Natural History

(Part of the Natural History Mosaic Program)

The group gathers beneath Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the largest terrestrial predators in the history of life on earth. He seems to have been able to eat up to 500 pounds of food in a single bite.

Required Texts:

Hacker, Diana. A Pocket Style Manual 5e.

Harrison, Ralph. The Elk of Pennsylvania.

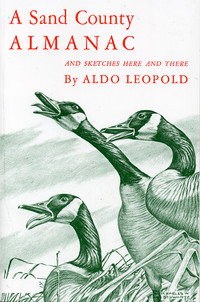

Leopold, Also. A Sand County Almanac.

Warner, William. Beautiful Swimmers.

Welch, Craig. Shell Games.

Fergus,Charles. Wildlife of Pennsylvania.

Your last name, first name. Natural History Field Notebook.

Online dictionaries: Oxford English for advanced definitions: http://www.oed.com

Merriam-Webster for regular use: http://www.britannica.com/ Dickinson website.

Handouts and required written classroom exercises

Are “wild” animals different when seen in sight of human habitation?

Course Aims and Expectations:

This course is designed to improve your skills as a writer of expository prose by emphasizing the genre of natural history writing. We will concentrate on a variety of writing problems and techniques, emphasizing specific skills necessary to a wide range of writing tasks: description, summary, narration, argumentation, analysis, and interpretation. In all cases, our focus will be on the natural world, natural history, and human connections to that world. Our numerous field trips to museums and field experiences in the wilds of Pennsylvania will form the basis of much of our writing. You will keep your own natural history journal that begins today and ends on the final day of classes, when it will be handed in; this journal will record, analyze, and otherwise create an experiential and intellectual document of your experiences with the nonhuman world during our entire semester. So, some of your writing will take place in the field or near the field, some more of it in the library or at your desk. Discussions of essay reading assignments will be supplemented by group workshop sessions and individual tutorials. Students will have the opportunity to critique one another’s work and to compare their essays to works by natural history writers of the past and present. The course aims to concentrate your attention on the precise stylistic details that lead to effective writing.

Why is it that human beings like to preserve and present dead animal bodies “as if” they were alive?

Essay Requirements:

–All essays must be typed: one-inch margins & double-spaced

–Assignments will specify a precise length for each essay

–Essays must be stapled or paper-clipped together

–Title page must include title, the author’s name, and the due date

–Essays due in class at 2:00 p.m. on the syllabus indicated date

–NO LATE PAPERS (or drafts) WILL BE ACCEPTED

Certain wild creatures, like the iconic snowy owl from Harry Potter, become powerful cultural symbols for entire generations. Professor Nichols saw seven (7!) of these remarkable birds in a rare “eruption” near the Flathead Indian reservation in Western Montana, far from their usual range nearer the Arctic.

Web Sites for Nature Writers

Dickinson Writing Center

English Department Writing Guidelines

Online Resources for Writers

Virginia Commonwealth University Nature Writing Web Links

Grading:

Grades will be based on the following distribution:

Essay 1 2 3 4 Revision In-Class Journal Exam-revision Writing

: . 10 10 10 10 20 10 10 20 = 100%

Students must complete all of these requirements in order to receive credit for the course.

Class Meetings, Readings, & Essay Due dates:

(T Th 2:00 p.m., K 152)

_____________________

August 27: First class meeting of full Mosaic 10 a.m.-12 noon. Kaufman 152

28 Tu Syllabus and in-class writing exercise: what is “nature”? what is “natural history”?

Students measure forearms and heights in order to compare Homo sapiens with other creatures to whom we are related: those with a spine and with a radius and an ulna (or comparable bones).

30 Th Essay #1 due (a natural object: assignment sheet attached). Provisional grade is dropped if it goes up on September 14 version (see below).

_____________________

September

4 Tu Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac. xiii-xix, pp. 3-137. What is good nature writing?

6 Th In-class exercise (sentences from student essays). Hacker & Sommers, “Clarity,” pp. 1-18

Recently hatched stinkpot turtles (coincidentally, one for each student) will soon be released back into a pond in the “wilds” of Wildwood in Central Pennsylvania.

______________________

11 Tu Hacker & Sommers, “Grammar,” pp. 19-53, Aldo Leopold, pp. 138 to end

14 Th Essay #1 revised (a natural object). Hand in for a final grade. Workshop.

15 Saturday SUSQUEHANNA RIVER TRIP

Mosaic students on the Susquehanna clean-up with the local chapter of the Sierra Club.

____________________________

18 Tu CHESAPEAKE BAY TRIP (be reading and finish Beautiful Swimmers)

Captain Wes, after decades as a waterman on the Bay (out of Smith Island), shows the students the intricacies of the crab-pot, before baiting and setting.

20 Th CHESAPEAKE BAY TRIP (discuss Beautiful Swimmers)

Paige Sanford of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) discusses the fish menhaden’s remarkable adaptations: mouth size, eye-spot, v-tail, and more.

____________________________

25 T Vocabulary. Bring natural history journal to class with Bay writing. Hacker & Sommers, “Punctuation,” pp. 55-74

A dubious student receives a “crab-hat,” thanks to vigorous grabbing by the Chesapeake Bay blue crab; Professor Wingert looks on with concern.

27 Th Read and bring The Elk of Pennsylvania booklet to class for discussion * * * Whistlestop Bookshop Reading, Prof. Nichols 4:30 p.m. * * *

28 Fr ELK COUNTY TRIP

A remarkable photo, in which a bull elk mistakes a bronze statue for a rival and attacks. Nature and culture, together again. (PA-DCNR)

_____________________________

October

2 Tu SMITHSONIAN, D.C., Trip. Pick a single exhibit space (write a two-page journal description of why the display is effective for the viewer)

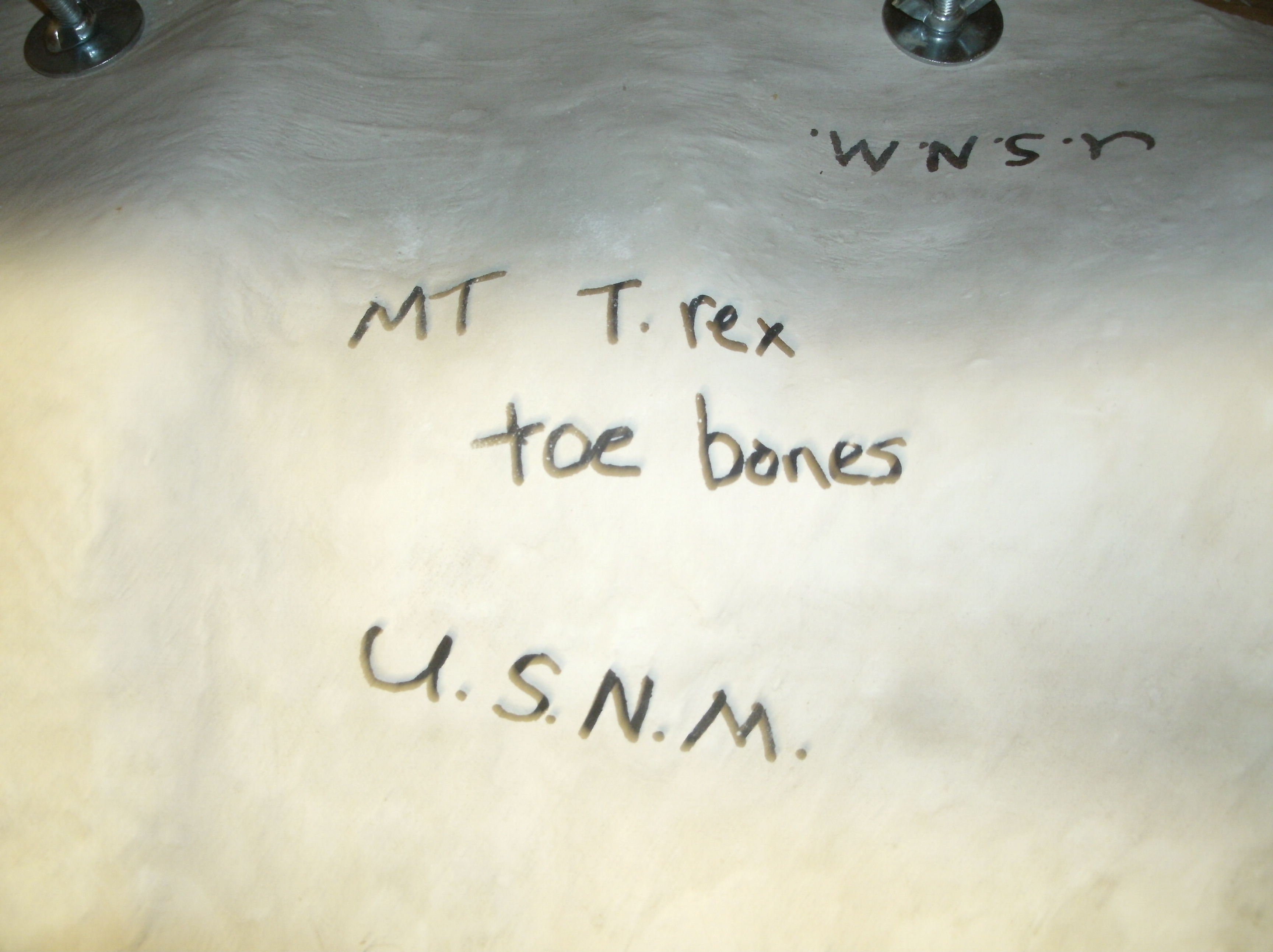

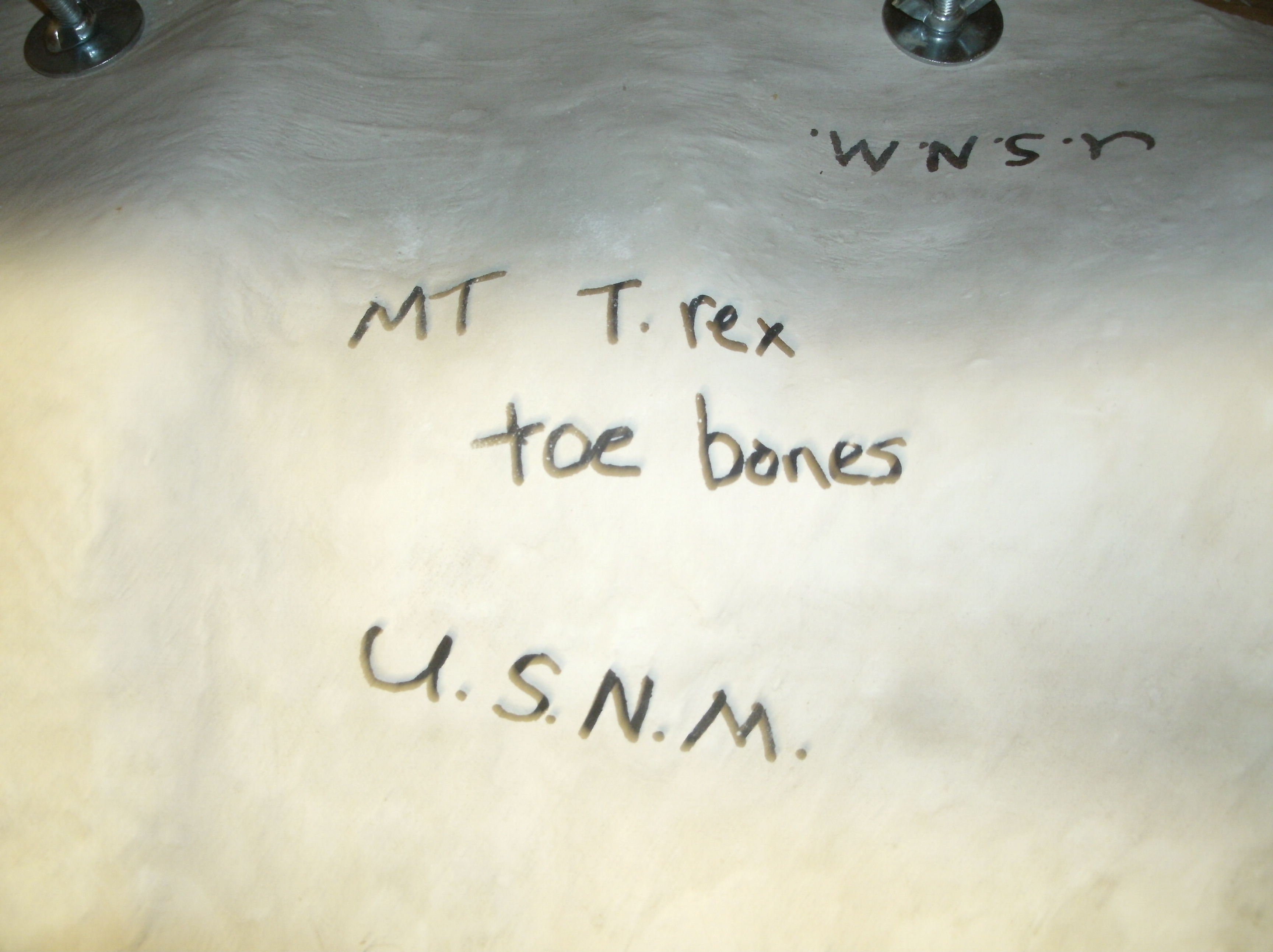

Students have the rare experience of a behind-the-scenes tour with David Bohaska in the Vertebrate Paleontology department at the Smithsonian; they were treated to an up-close-and-personal tour of T. rex, Triceratops, Apatosaurus fossils, and many others in the deep basement of the museum.

How does it feel to lean against a shelf in the Smithsonian basement and suddenly notice what it contains: (Montana, Tyrannosaurus rex toe bones, United States National Museum). Very cool!

4 Th NO CLASS Essay # 2 due (narration) (submit electronically to me by 3:15 p.m.)

One drawer behind the Smithsonian scenes contains this remarkable piece of mammoth skin and fur. Thawed out from a glacier that held it for many millennia, this specimen allowed Dickinson students and professors to touch an organic piece of evolutionary history.

______________________________

9 Tu In-class exercise: “To see the wind with a man his eyes.” Hacker & Sommers, “Mechanics,” pp. 76-87

Titanoboa, the largest (prehistoric) snake ever discovered, was 50 feet long and weighed more than a ton when he roamed the jungles of South America more than 50 million years ago. His vertebrae dwarf those of any living snake, and he could gobble up full-sized crocodilians without ill effects. He was discovered in a fantastic fossil-site full of turtles–as big as a living-room rug–and post-dinosaur lizards much larger than any alive today.

11 Th Charles Fergus, Wildlife of Pennsylvania. Pick a single CAPITALIZED SECTION from this book [ex. COYOTE, ELK, PUDDLE DUCKS, WILD TURKEY, LAND SALAMANDERS, POND AND MARSH TURTLES, WATER SNAKE]). At the start of class hand in a single double-spaced page about why this entry in Fergus’s book is well-written, using examples of language as details; then be prepared with notes to tell the class why your entry is well-written.

A Triceratops skull towers in the unbelievable basement of the Smithsonian.

________________________________

16 T FALL PAUSE (No Class)

18 Th Craig Welch, Shell Games. 1-115 Discuss

Trilobites were one of the most widespread and successful creatures ever to live on earth. They roamed the seas for over two hundred million years, finally disappearing as part of a mass extinction as the Permian era ended. Today, they remain only as fossil specimens in museums, private collections, and numerous geological sites around the world.

19 F STATE MUSEUM IN HARRISBURG

_________________________________

23 T Craig Welch, Shell Games 116-240. Hacker & Sommers, “Research,” pp. 88-103

The Mosaic class caught three large snapping turtles during its project to protect the painted turtle from the slider. As a recent paper notes: “Sliders [have been] released from captivity, mainly as a result of the pet trade. Sliders are aggressive omnivores and are likely to compete for food, nest sites and basking sites with many species of native aquatic and terrestrial turtles.”*

25 Th Your field journal as a text. Bring you best paragraph, typed with copies for 12.

26 F HAWK-WATCH AT WAGGONER’S GAP

The Waggoner’s Gap rock-pile, one of the premier hawk watching sites on Pennsylvania’s spine of the Appalachian Mountains. No experience equals the sight of a peregrine falcon or a golden eagle coming in low along the ridge, racing south on the winds of autumn.

__________________________________

28 S JOSEPH PRIESTLEY’S HOUSE IN NORTHUMBERLAND, PA

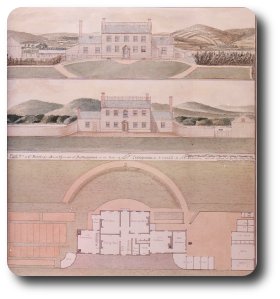

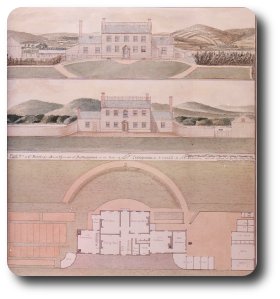

The Joseph Priestley House in Northumberland, PA, just up the Susquehanna River from Dickinson College. This drawing–the Lambourne Plan (1800)–was only rediscovered in 1983 in the Royal Society Archives in London; the house remains substantially the same today. It contains the laboratory in which Priestley identified carbon monoxide and the room that once housed his library of over 1,500 volumes, one of the largest in America at the time.

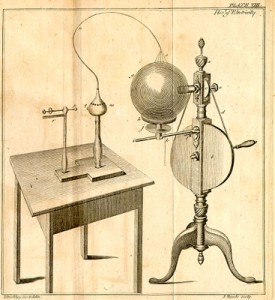

Priestley’s apparatus, some of which is now on display in the Archives of Dickinson College.

29 M PITTSBURGH: PHIPP’S CONSERVATORY (ARBORETUM)

The Carnegie Museum not only has T. rex skeletons; it has THE T. rex skeleton: the holotype, the skeleton example from which Tyrannosaurus rex (“tyrant lizard king”) was named back in 1905. We were lucky enough to be able to touch the serrated teeth and jaw of that remarkable fossil.

30 T PITTSBURGH: CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Living birds are not related to dinosaurs; they ARE dinosaurs. The DNA record and other morphological evidence about the origin of feathers, warm-bloodedness, and other characteristics (look at any bird’s claws, its skin, and its skeleton) prove this beyond debate.

Dr. Dave Berman, the Carnegie Museum’s Permian tetrapod expert, shows us the oldest bipedal creature on earth, a specimen (white box) he and his colleagues discovered at a quarry in Germany.

31 W PITTSBURGH: NATIONAL AVIARY

Steller’s sea-eagle, the largest eagle in the world, as close up as the class was able to see him at the National Aviary in Pittsburgh.

November 1 Th Essay #3 due: analyze Warner’s or Welch’s style. Animal rights: class positions, debate and discuss

Feeding time in the rain forest at the aviary; a little worm on the extended palm is all it takes.

__________________________________

6 T Essay (bring draft notes for Essay #4) Hacker & Sommers, Glossaries, pp. 259-278

8 Th NO CLASS Critique with a classmate or visit the Writing Center.

___________________________________

13 T Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac. xiii-xix, pp. 3-137. Link to your own experiences this term. In-class writing.

The ur-text, the foundational document, of all modern American nature writing.

15 Th Aldo Leopold, pp. 138 to end. Link to what you have learned this term. Discuss.

___________________________________

20 T FINAL CLASS Essay #4 due (animal rights: interpretation)

* * * * * *

The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. . . . “The question is not “Can they reason?” nor, “Can they talk?” but, “Can they suffer?” –Jeremy Bentham (1789)

Jeremy Bentham, founder of utilitarian philosophy and an early animal rights advocate. Here is Bentham’s “auto-icon” (his “skeletonized” remains plus a wax head, preserved forever in the lobby of University College London). Bentham suggested that such a utilitarian use of his dead body would be helpful to future college decision makers; they could look at this suit of clothes–inhabited by the remains of the great man–and think, “What would Jeremy do?” Surely one of the strangest natural history specimens in the world. (Photo credit: Michael Reeve)

* * * * * *

22 Th Thanksgiving (No Class)

___________________________________

29 Th 1st Revision Due in Kaufman 192 2:00 P.M. (Essays 2-4)

30 Fr Draft of IR/IS projects due

___________________________________

December 13 Th FINAL EXAM (2nd Revision) Kaufman 192 by 5:00 p.m.

14 Friday Final IR/IS due FINAL MOSAIC DINNER

___________________________________

Professor Ashton Nichols Kaufman 192, East College 305.

What about “animals” that are tens of millions–or hundreds of millions–of years old?

********************************************

Essay #1

A Natural Object

Spend at least one uninterrupted hour observing a natural object. The object can be large (star, sun, cloud, mountain), small (grain of sand, flower, ant, leaf) or in between (stream, tree, turkey vulture, rock). Your object should be one that had not been shaped or visibly affected by humans. You should observe it as carefully as possible. Do not engage in any other activity (conversation, writing, reading, etc.) during your observation. No Walkmans allowed!

What did you learn as a result of this experience? Write a 750-1,000 word (three to four typed pages) essay that explains to the members of our class what you knew at the end of this hour that you did not know before your observation began. Write with care and attention to the precise details of your experience. Your essay should have a thesis (a central controlling idea) and a clear organizational principle (chronological, psychological association, logical progression). Avoid errors of grammar, syntax, and spelling. Proofread you work carefully.

This essay is due at the start of class on Thursday, August 30, at 2:00 p.m. It should be typed, double-spaced, and should have a title page that includes a title that you have composed, your name, and the date

NO LATE PAPERS WILL BE ACCEPTED

Sometimes creatures–like this eye-spotted luna moth–are appreciated by humans primarily aesthetically: for their physical beauty, their incredible colors, or shapes, or sizes. Notice the ragged tears on the wing-edges, signs of the wear-and-tear of normal life in the field.* (*selected photos thanks to Emily Stanley)

**************************

Sometimes it is hard to believe that the colors of living things are all “natural.”*

NATURAL HISTORY FIELD JOURNAL

For our “Writing About Natural History” class, you will keep your own natural history journal. It begins today and ends on the final day of classes, when it will be handed in to me. This journal will describe, narrate, analyze, interpret and otherwise create an experiential and intellectual record of your experiences with the nonhuman world during our entire semester. This field journal will have no length requirement; it must, however, be complete. Do not let us find that you have no entry about our trip to the Chesapeake Bay. Do not give your readers half-a-page about the largest herd of elk east of the Mississippi. This journal should accompany you on all of our trips away from Dickinson and Carlisle.

You are encouraged to share your journal with your classmates, with other students, with professors, or with your family. You should feel free to ask me for advice or suggestions during the term, and you should feel free to copy “commonplace” selections into your your own journal (from Thoreau or Annie Dillard Emerson, from Wordsworth or William Warner); just make sure that you always indicate when the words you write are not your own. Consider all of our texts, classes, and discussions as source material for your own journal writing. Writing is a social and cultural practice. Your own writing always benefits when you see yourself as part of a reading and writing group of interested literate individuals.

I may collect these journals at any time during the semester. I may ask to see the journal—individually or collectively—at any time. I may ask you to read aloud from your journal on any day our class meets. I may ask you to make use of your journal for additional formal or informal writing exercises. In short, this writing will be a key component of your work for this class. In addition to your five formal (graded) essays and two formal revisions, this journal will form the basis for the bulk of your writing during the term. Let your journal be influenced by the other writing we do in and for class. Let your style be influenced by the readings we are doing and reading that you are doing for your other Mosaic classes. Take advice from your classmates, or ignore it; take advice from me and your other professors.

Keep your journal in a separate notebook that can be handed in to me or can be shared among your classmates at any time. It must be written in ink (longhand or printed), or printed out on computer sheets that can be included in a journal format. You can keep your rough notes or drafts elsewhere. Your journal should be work that you would want to read aloud to the class or that someone else could read aloud. I will collect these on November 20 for the last time and will hand them back to you by the end of term.

Let me know if you have questions.

The predator-prey relationship is almost as old as the animal kingdom; it must have been a very early evolutionary adaptation, designed to insure another source of nutrition: feeding on one’s own kind–animals–as opposed to plants (leaves) or minerals (salt).*

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Visible evolution: a Smithsonian display presents the remarkable alteration of a toothed-whale’s teeth into baleen, the filter feeding devices now used by today’s baleen whales.

A giant ground sloth, of the kind that roamed North and South America during the Pleistocene, over 10,000 years ago, still standing his ground in a display at the Smithsonian.

Natural History Mosaic

Independent Research/Independent Study

Fall 2012

(A course credit in the Natural History Mosaic Program)

The class gathers around the Smithsonian’s iconic bull elephant; at 8 tons and 14 feet tall, it is an astonishingly large example of an African elephant. He has stood in this lobby since 1959.

Course Aims and Expectations:

This credit—the 4th of your credits for the Natural History mosaic—will allow you to deepen you knowledge of one of our topics under the guidance of one or two professors. You will pick a topic during the first week of the semester, refine that topic during the early weeks of the semester, and then spend the remainder of the fall term preparing your final research or study project. The course will also provide an opportunity for peer editing and comment as well as regular interactions with your supervising professor/s.

Requirements:

Because of the faculty teaching assignments for the semester, seven of you will work primarily with Professor Nichols, two each primarily with Professors Key and Wingert. Those of you who know that your topics are primarily scientific (lab based, primary research, specimens, data collection and analysis) will need to decide whether your focus leans toward paleontology and marine biology (Professor Key or terrestrial biology and environmental science (Professor Wingert). Those of you whose work will fall in the disciplines of history, literature, cultural studies—and the like—will automatically work with Professor Nichols. A number of you may by assigned to Prof. Nichols but consult regularly with Prof. Key or Wingert.

Does “wilderness” become a different space once human beings arrive there? Can there be any true wilderness left once the earth has been completely mapped, and charted, and photographed, and Googled?

Possible Independent Study Projects

Independent Study is a broad, literature-based investigation involving synthesis of already published literature and write up based on your own thesis statement and careful textual research. Possible ideas might include:

Prof. Nichols:

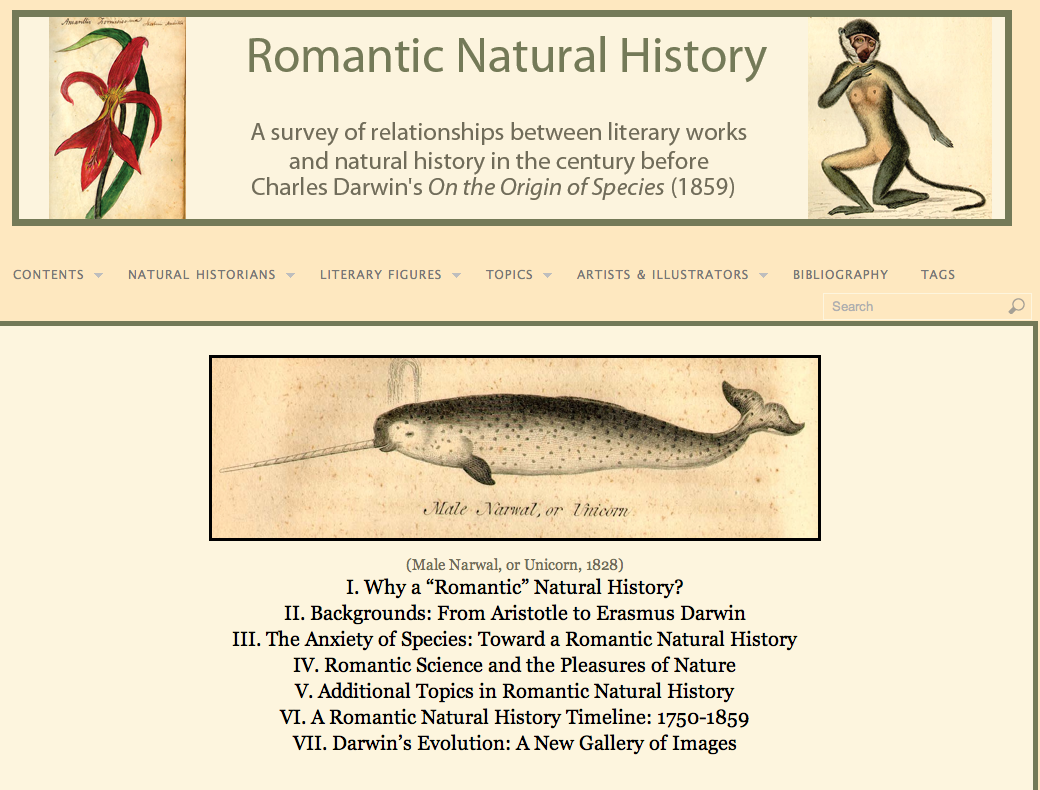

Professor Nichols’s Romantic Natural History hypertext website reveals how much scientists cared about poetry and poets cared about science in the century before Darwin’s Origin. See: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/romnat/

–history of a museum (Smithsonian, Carnegie) or collection within a museum (animal halls, fossils, rocks and minerals)

–critical biography of an author (Aldo Leopold, Annie Dillard)

–history of several natural history books or a series of field guides (Peterson Series, National Geographic, Audubon)

–essay about H. D. Thoreau (as a naturalist or a writer) or a more general biography

–architectural and/or historical study of the Joseph Priestley House 1794-1804

–essay about John James Audubon: his life, his fieldwork, his artistry

A happy entomologist shows off her careful (and sustainable) collection.

Prof. Key:

–the role of mass extinction in the history of biodiversity

— was T. rex a predator or a scavenger

— some aspect of the evolution of humans

— develop a new display on paleontology, evolution, or biodiversity (or a combination) for our new Kaufman museum

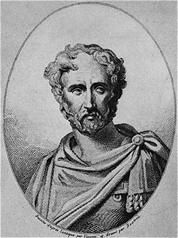

The first natural historian, Pliny the Elder. Pliny died while on an excursion to gain a close-up view of the great eruption of Vesuvius in August of 79 AD.

Possible Independent Research Projects:

Independent Research is a focused investigation involving actual specimens, data collection, data analysis, and write up. Possible ideas might include:

Prof. Key:

— biology or ecology of estuarine animals (e.g., Chesapeake Bay blue crab)

— evolutionary or paleoecological process (e.g., relationship of shark tooth shape to ease of penetration or mammal stride length vs. speed

–paleoenvironmental interpretation of clam fossil slab by modeling of clam shell behavior in a wave tank)

A bug-box collected under environmentally sustainable conditions.

Prof. Wingert:

— comparison of barn owl diet with long-eared owl

— nitrogen comparison of two streams: one stream in a deer impacted area and the other in a healthy forest

— egg counts in Gray tree frog females

— macro assessment of three streams: one in a residential area, the other in agricultural area, and a control stream in a forested environment

You will pick a topic that will be approved by the professors by Friday August 31 and fill out the necessary registration form for the Registrar. This class will have regularly scheduled meeting times—9:00 a.m. Wednesday, 1:30 p.m. Friday–but it will only use that time for the first several weeks of class. Then you will be working largely on your own and with individual meetings with your assigned professor (seven with Professor Nichols, two each with Professors Key and Wingert). We may have borderline research/study projects that will be shared between professors. We will keep these time slots open for individual meetings as the semester progresses.

August 29 9 a.m. What is an Independent Study or Research Project: How does it work?

31 1:30 p.m. Final decision and registration for your Independent Research/Study course

September 5 9 a.m. First meeting to plan schedules for semester

7 1:30 p.m. Individual meeting with professors

12 9 a.m. Individual meetings with professors

27 Th **Whistlestop Bookshop Reading, Prof. Nichols 4:30 p.m.***

c. November 28 15 minute oral presentations

November 30 F First draft of Independent Study/Research project due

December 14 F Final version due

Let us know if you have questions.

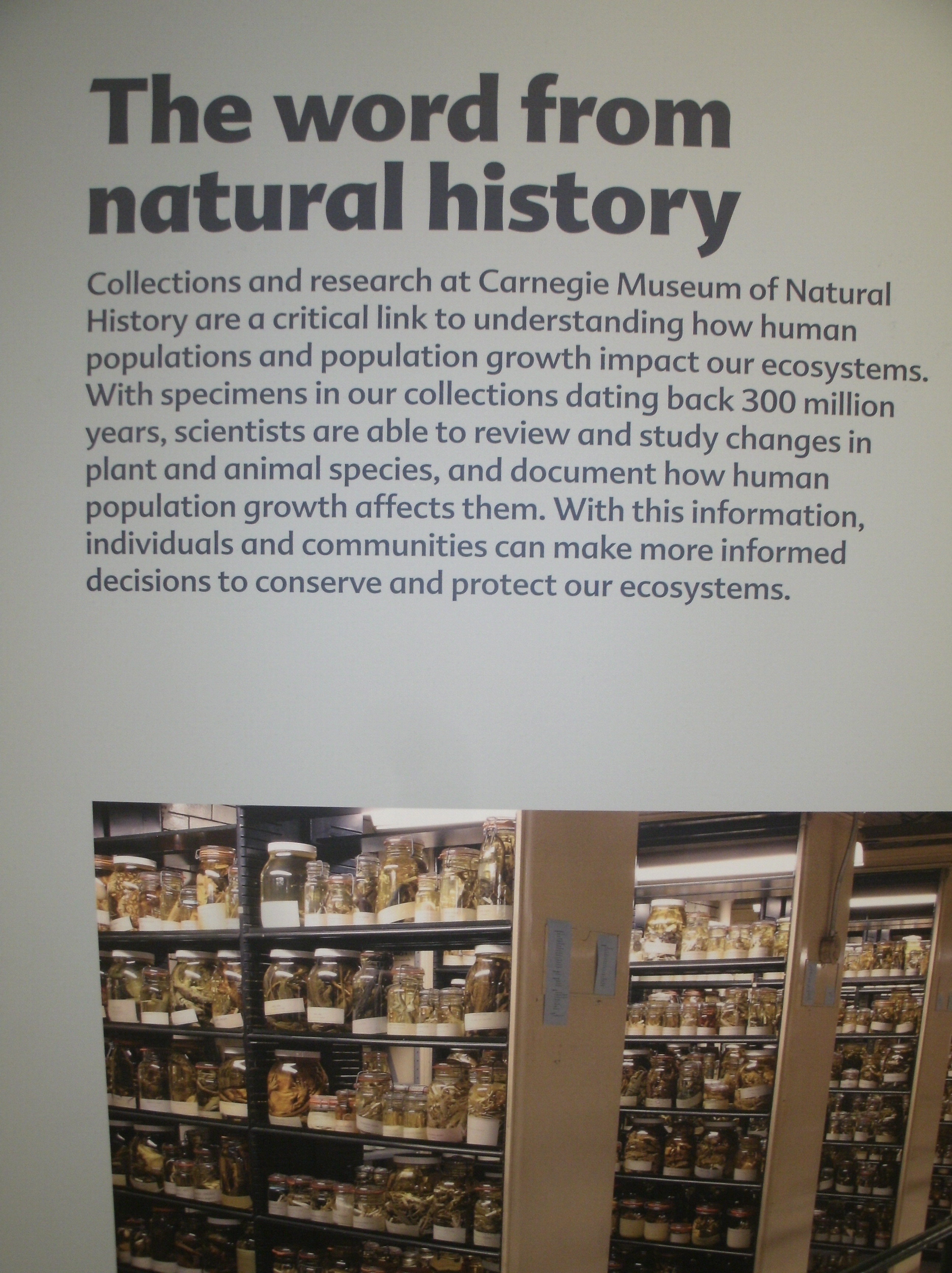

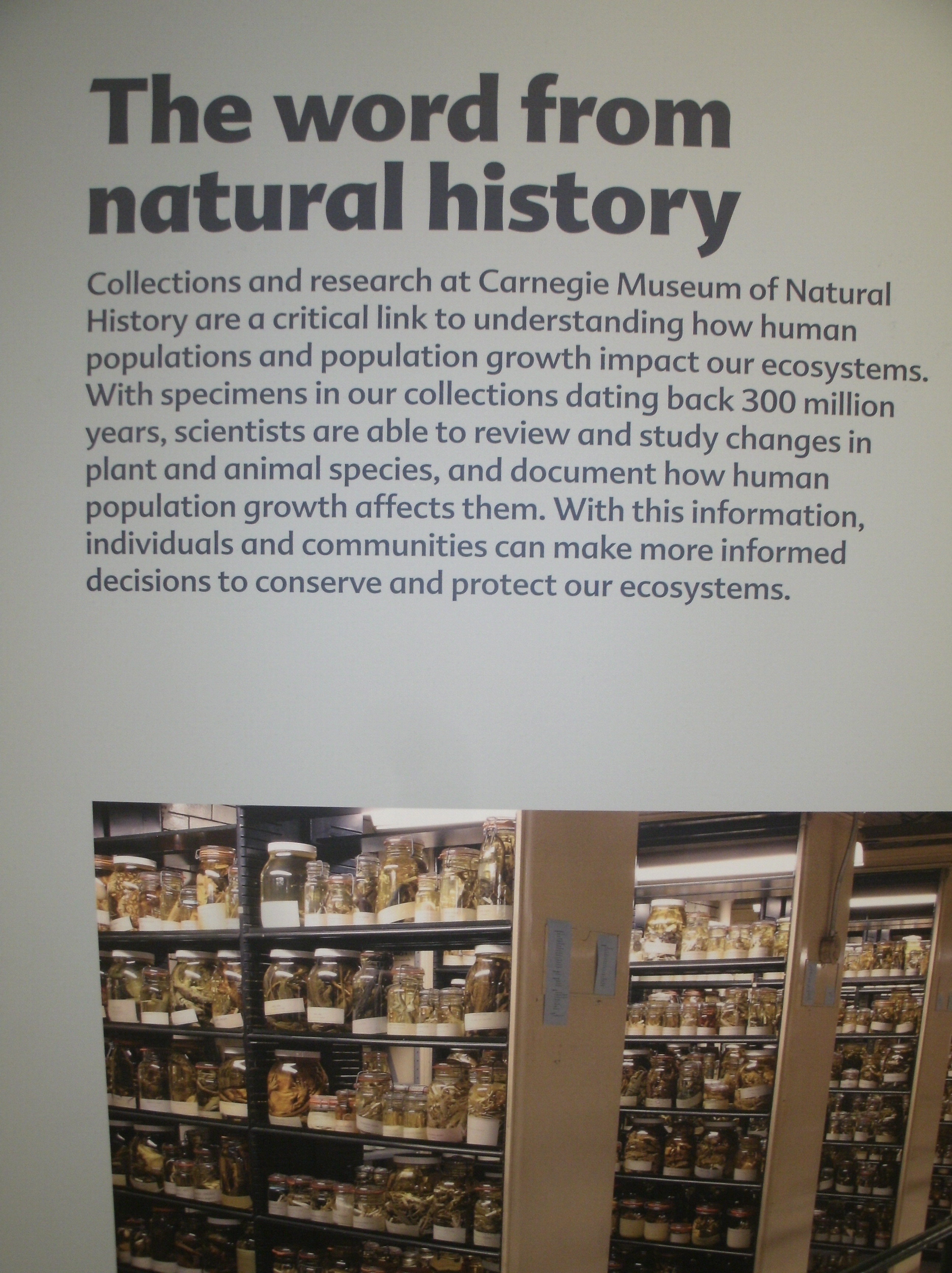

Why is NATURAL HISTORY so important? (Click on this image–above–to appreciate the significance of natural history collections and collecting in the 21st century.)

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The Mosaic class gathers around a bust of Spencer Fullerton Baird, 19th-century student and professor at Dickinson who was later the second Secretary of the Smithsonian. Taught to draw birds by John James Audubon, Baird took two boxcars full of natural history specimens with him to Washington, D.C., from Carlisle, PA. He was responsible for making the Smithsonian the nation’s great museum; its collections grew from 6,000 to 2,000,000 specimens during his tenure. Some of his birds are still visible. (Professor Key smiles at lower right.)

Ashton Nichols, K 192, EC 305

see also: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ZqNrk4h7N0

and: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBr9pTItVX0&feature=relmfu

* * * * * * * * * * * *

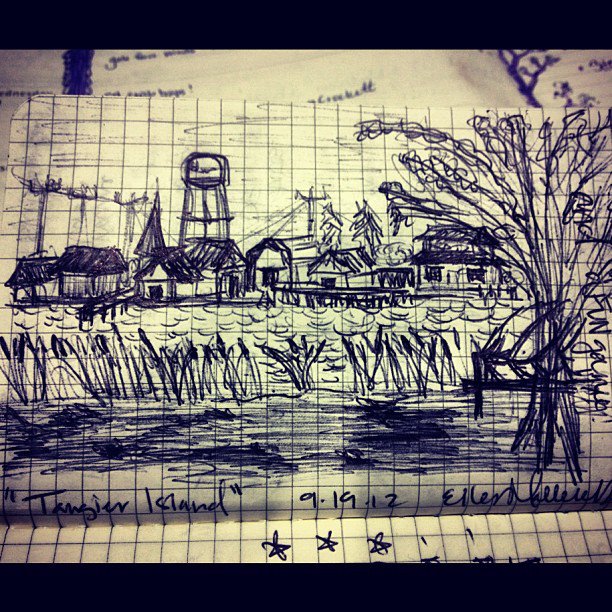

Eller’s sketch of Tangier Island, Virginia, drawn from Port Isobel, the tiny uninhabited island where we stayed while studying the Chesapeake Bay. Tangier was named by Captain John Smith in 1608 for its resemblance to the coast of North Africa.

Academic Accommodation:

Dickinson College makes reasonable academic accommodations for students with documented disabilities. I am available to discuss the implementation of those accommodations. Students requesting accommodations must first register with Disability Services to verify their eligibility. After documentation review, Marni Jones, Director of Learning Skills and Disability Services, will provide eligible students with accommodation letters for their professors. Students must obtain a new letter every semester and meet with each relevant professor prior to any accommodations being implemented. These meetings should occur during the first three weeks of the semester (except for unusual circumstances), and at least one week before any testing accommodations. Disability Services is located in Biddle House. Address inquiries to Stephanie Anderberg at 717-245-1734 or email disabilityservices@dickinson.edu. For more information, see the Disability Serviceswebsite: www.dickinson.edu/disabilityservices.

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers [and sisters].” (apologies to Shakespeare)