Integrating Childhood, Children’s, and Youth History into High School History Courses

Integrating Childhood, Children’s, and Youth History into High School History Courses

For three years after graduation from college, I taught social studies – all of them – in a small high school in rural Texas. I remember feeling alternately overwhelmed by (“how can I cover all of this?”) and constrained by (“why can’t I teach this?”) state-mandated learning objectives. Though I now teach at the university level, I am married to a high school teacher who reminds me, especially in the spring, how much pressure there is for secondary educators to “teach the test” so that their students will perform well on state exams.

All of this is to say: I feel your pain. I have no desire to add to your burden, high school teachers of America & the World. When I ask you to consider integrating childhood, children’s and youth history into your classes, I do so in the hopes that it will be an effective way to both cover those required objectives AND get your students excited about history. While I will mention sources from Russia that you can use in American history or world history, what I’m suggesting here can be applied to all kinds of sources on childhood around the world. I’m not proposing a rewrite of your existing curriculum, just some tweaking; speaking as a university educator, I would be really happy to know that incoming students had been introduced to the idea of children’s history.

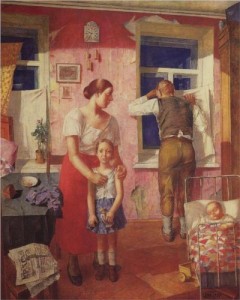

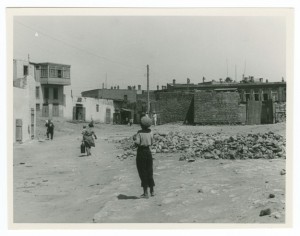

Since most states require educators to use a “variety of rich primary and secondary source material,”[1] I’ll begin by suggesting a simple way to introduce this topic to your students: find art, photographs, artifacts, or documents about or created by children that relate to a unit or lesson you already cover. If you have lesson on the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, add this contemporary artwork by Lithuanian children about the gulag in conjunction with the lesson plan offered at the Gulag History site. This allows you to talk briefly about children in the gulag and children of gulag survivors, how memory/history is taught, and the fall of communism. Using visuals in your classroom activities not only helps develop primary source analysis, but also introduces the arts and media. A discussion of totalitarianism or the Cold War could utilize the Soviet poster and brief descriptor here.

The Children and Youth in History site, created by George Mason University and University of Missouri-Kansas City, is an excellent resource for students and teachers. It includes single- lesson plans called Case Studies that are written by educators and include a step-by-step guide for using a particular document or image with secondary students. For example, one of these case studies is based on the Thälmann Pioneers of East Germany. Additionally, there are fifteen Teaching Modules that provide an overview of larger topics such as “Childhood in the Slave Trade” or “Children during the Black Death,” a number of resources, teaching strategies, lesson plans, and a document-based question.

The beauty of this topic is that it can fit a variety of historical events, especially for the modern period. A study of industrialization can include child labor testimonies from Great Britain, Marx on child labor and education, and an excerpt from Boris Gorshkov’s Factory Children. A study of the Cold War could compare American and Soviet cartoons about the enemy. Any required social studies skills can be emphasized when considering images or documents by or about children.

A couple of new books are particularly well-suited to use in secondary history classes. Eugene Yelchin’s Newbery Honor Book on the Stalinist Terror, Breaking Stalin’s Nose, is a gripping read. The book has an attractive and accessible (though not particularly deep) discussion of Soviet life referenced in the book at http://www.eugeneyelchinbooks.com/breakingstalinsnose/index.php to help students understand the story better. Advanced students might compare Yelchin’s book to Lydia Chukovskaia’s novella Sofia Petrovna (the Terror through the eyes of a mother) to discuss Soviet society and politics from two perspectives. Another notable book is Esther Hautzig’s The Endless Steppe: Growing Up in Siberia. The author recalls her childhood as a Polish deportee in the Soviet Union during World War II. She conveys a sense of what life was like in the USSR during the war.

My appeal to you to incorporate childhood into your history courses is threefold: 1.) Pedagogues tell us that students need “hooks” in order to connect new information with something they already know. Children’s history has an advantage here because your students will feel that “childhood” is familiar territory, even if you are talking about children or childhood in another time or place; 2.) You can hit multiple learning objectives by discussing childhood without adding burdensome work to your full plate; and 3.) your students will respond to these sources, which will help them enjoy history more than they think they do!

[1] I am in the state of Texas, so I am referencing Chapter 113 of the TEKS (Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills) for Social Studies, Subsection C., available at http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter113/ch113c.html.