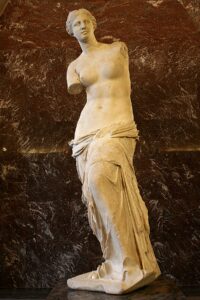

We know that “Michael Field” – Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper – were both aunt and cousin and considered themselves married. We also know that they were, for a significant period of time, deeply surrounding themselves with Ancient Greek and pagan traditions. It informed their writing. Informed by both their sixteen-year age gap and that Katherine helped raise Edith when she was young, before they intertwined their lives into shared journals and shared rings, I want to offer “Michael Field’s” poems in the context of the Ancient Greek tradition of pederasty.

Pederasty isn’t difficult to define but it can be difficult to discern. When I originally thought to write this post, I didn’t anticipate the grey area that a concept, originating in a society with different accepted behavior and norms, has with our more current understanding of child-adult developmental differences, consent, and standards for behavior. According to Walter Penrose, Jr. in “A World Away from Ours: Homoeroticism in the Classics Classroom,” when distinguishing pederasty from pedophilia, writes that “Ancient Greek pederasty, the other hand, when it conformed to cultural norms, was controlled, involved education of the youth by his older lover, and in some cases may not have been sexual at all” (238).

Penrose goes on to cite primary sources that refer to the “boy” in a pederastic relationship to be one who “had attained full height;” that parental or guardian consent was required before a pederastic relationship could occur and that a chaperone might be present during the meetings. He makes sure to write that, at this period in time, the acceptable age for girls to enter into marriage was also much younger than is generally accepted today, and that “boy” as terminology could refer to a more adolescent boy as well as a man in a lower social class or who was enslaved.[1] He notes that there seems to be some laws or regulations preventing nonconsensual or coerced relationships. He also acknowledges that sexual assault and rape did happen, but that pederastic relationships were ideally regulated, consented to, and without the connotations of pedophilia today.

The most interesting thing that Penrose cites about Ancient Greek pederastic relationships was its emphasis on education, rather than any form of sexual relationship. In some forms of the pederastic relationship, the older man could enter into a ritualistic “capture” of the younger boy, mimicking some traditional practices of heterosexual marriage, as in Sparta. Pederasty, used as a form of apprenticeship, could encompass spiritual love rather than physical, though of course as a concept it was nuanced.

“Michael Field,” then, can be viewed as encompassing the ideals of Ancient Greek pederasty. They felt romantic love for each other and it is assumed that they had a sexual relationship, but given their age gap and their focus on artistry and writing together, in some ways their relationship embodies the pederastic emphasis on education. Additionally, the concept of pederasty being a form of socially-accepted same-sex marriage in the ancient tradition, if they were aware of it, was likely alluring for them.

Keep this nuanced understanding of pederasty in mind when thinking about “Michael Field” and their love for the traditions and concepts of Ancient Greece. In Underneath the Bough, their poem “Love doth never know,” Katherine and Edith write that “Were its hopes removed,/ Where itself disproved/ By cold reason,/ In its happy season/ Love would be beloved” (11). This book is surrounded by references to classic mythos. In this poem, “Michael Field” is asking: even if the love between people has become hopeless and “itself disproved,” it still would have been “beloved” in “its happy season.” Although their relationship is a bit ethically questionable and “disproved/ by cold reason,” as is pederasty, in our current understanding of accepted behavior, would not the real love felt then, in “its happy season,” still be “beloved?”

[1] He also notes that the concept of “childhood” or “adolescence” as necessary developmental phases into adulthood is a much more modern practice – it was more common for a child to begin working very young. One must also, Penrose says, take into account shorter lifespans and so shorter developmental time periods.