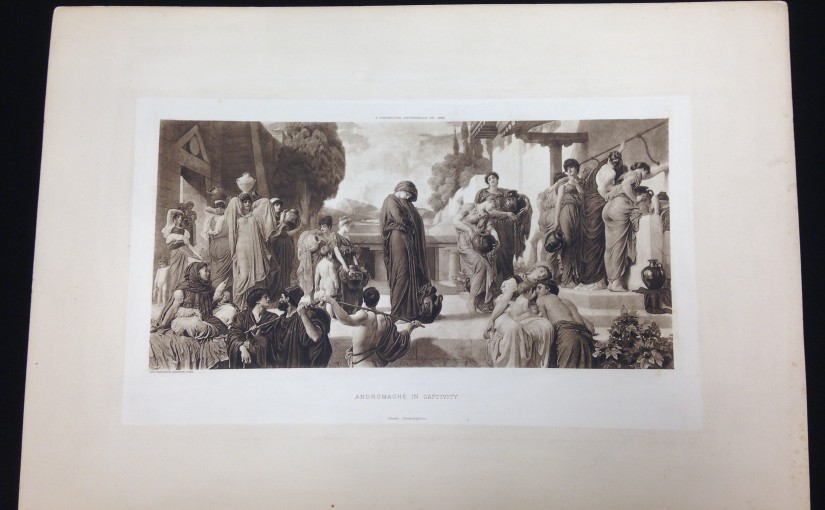

This piece– “Andromache in Captivity”–is a reference to the character Andromache from Greek mythology. After Troy fell to the Greeks, Neoptolemus forcibly takes Andromache as his concubine, enslaves her brother, and murders her child. This image depicts Andromache in the aftermath of the Trojan War, when she is living as a captive in a foreign land.

In the image, Andromache’s suffering at the hands of her captor is being used as a propaganda tool. In colored versions of the art piece, Andromache’s skin is quite pale, in contrast to the darker olive and brown tones of the people in the street. Additionally, she is dressed in black clothing (which for Victorians signified deep mourning) in contrast with the bright robes of her captors. Andromache is mourning the loss of her home, her family, and likely her freedom (or purity, perhaps), while her captors celebrate and debauch themselves in the streets.

Furthermore, Andromache has been painted as the Western victim of a decadent and savage society. Notice that the other people in the image show lots of skin (some are even nude), while Andromache is covered head to foot. By subtly contrasting color of textiles and fullness of cover, the painter implies that Andromache is pure while her captors (and their women) are less civilized and more savage. When looking at the painting, it becomes clear that many of the figures, especially the women, appear to be watching Andromache. Their stares indicate that Andromache is merely an object or a spectacle, underscoring her lack of agency and utter powerlessness.

Additionally, fears that European women would be kidnapped and raped by foreign men played a large role in the justification and the proliferation of colonialism. Artwork such as this fuels the notion that foreign cultures (here, the Greeks) pose a danger to white, Western women and ought to be treated as a threat. Of course, this justification of colonialism is ironic, because colonizers posed a significant danger to foreign women. Indeed, fears of foreign men raping white women were weaponized by colonizers to justify the colonial mission, which often included raping foreign women with impunity. Analyzing images, such as Andromache in Captivity, illuminate the ways in which colonialism was represented and justified in art and culture, and can be helpful in understanding the role of art in shaping and circulating the (narrow) view of foreign cultures.