“Think of her as you thought of the first woman who quickened the pulses within you that the rest of her sex had no art to stir. Let the kind, candid blue eyes meet yours, as they met mine, with the one matchless look which we both remember so well. Let her voice speak the music that you once loved best, attuned as sweetly to your ear as to mine. Let her footstep, as she comes and goes, in these pages, be like that other footstep to whose airy fall your own heart once beat time. Take her as the visionary nursling of your own fancy; and she will grow upon you, all the more clearly, as the living woman who dwells in mine.” The Woman in White, Project Gutenberg

In Walter Hartright’s imagining of Laura Fairlie, he literally strips her identity from her: instead of granting her a shred of individuality or personhood, he presents her as an utter blank, depicted as a woman – any woman – who the (presumed male) reader found attractive. Walter describes no character, no personal quirks, no endearing qualities, which Laura possesses. In the most descriptive passage he accords to Laura, he transposes Laura the person with Laura as a stand-in for male masturbatory fantasy of a woman.

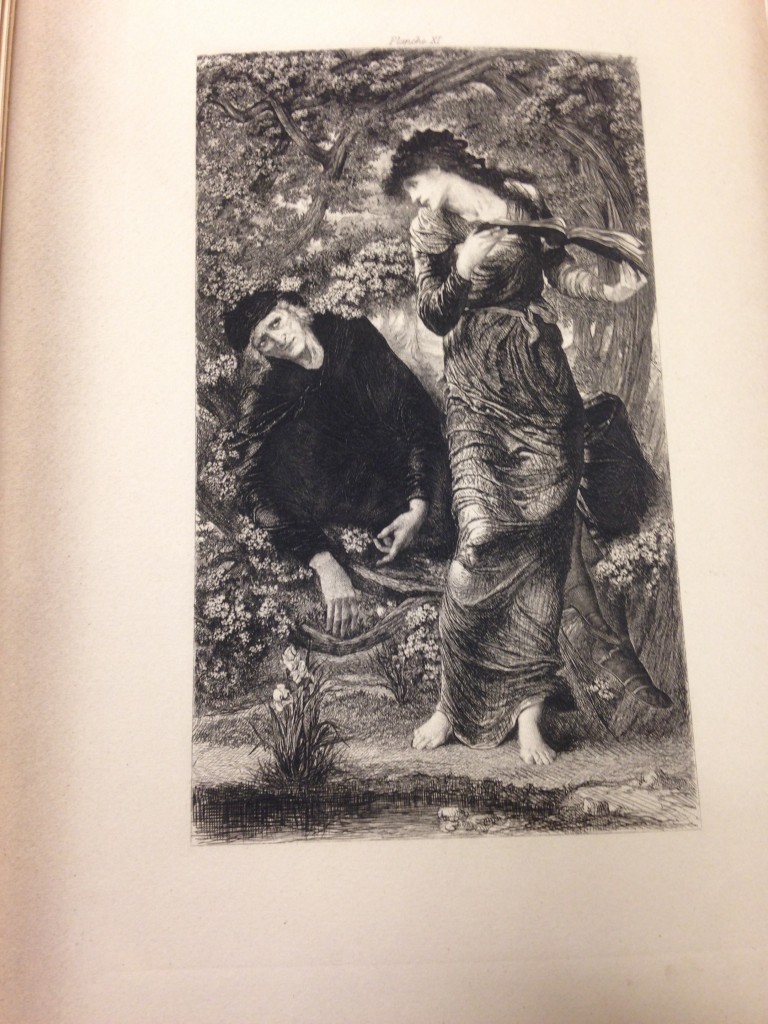

On an even more disturbing note, Walter describes Laura as the woman who lives in his fancy (fantasy): if the reader “takes her” into his own “fancy,” the woman who Walter encourages the reader to think of as Laura will grow stronger within the fancy in the same way “as the living woman who dwells in mine” – in other words, in Walter’s fancy. “Fancy” here means imagination, fantasy, invention, dream – Laura lives in Walter’s head, not in her own self or even her own body – and this dream-like quality echoes the dreamed woman in Christina Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio.”

The “nameless girl” (line 6) reflects Walter’s refusal to describe Laura’s actual identity; the girl of the paintings has no name, no identity except her face. In the same way, Walter describes Laura’s physical attributes – eyes, voice, footstep – without lingering on her selfhood, the qualities that make her herself, or even giving her a name, rather encouraging the reader to substitute another woman’s self and name in order to increase male pleasure in the conception of Laura.

Rossetti describes the eponymous artist as “feed[ing] upon her face by day and night” (line 9), in the same way that Walter “feeds” upon the watercolor of Laura, fetishizing its physical presence in the same way he fetishized Laura’s physicality while her body was present. The metaphor of consumption encompasses the mental/bodily possession of Laura that Walter craves as well as the fetishization of her body. If Walter acts as the artist in Rossetti’s poem, he is also a reversal of the artist, transferring Laura onto all attractive woman rather than turning all women into her. However, the concept of consumption stands: rather than allowing Laura to stand on her own, to claim her own identity, Walter and Rossetti’s artist prefer to consume the “beloved” into themselves, projecting their own ideas of the female self onto an idealized, masturbatory fantasy of a woman.

The last two lines of Rossetti’s poem perpetuate the projection of false ideals onto an actual woman: “Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;/Not as she is, but as she fills his dream” (lines 13-14). The repetition of “not as she is” emphasizes the falsity of the male artist’s conceptualization of the woman, just as Walter’s description of Laura has nothing to do with Laura herself. “As she fills his dream” directly echoes Walter’s creepy line about having Laura within his fancy; these two women, the blank of the artist’s model and the blank of Laura, have been consumed and subsumed by their male idealizers. Idealization is dangerous and unreal, and it always has a quality of fantasy and falseness. The false idols of women that the artist and Walter create are absolutely nothing like their real counterparts: we see the fictional Laura and the nameless girl as figments of the male imagination, neither how they actually are nor how they themselves think they are, but solely as the men around them think they should be.