Perhaps the last thing that comes to mind when reading Christina Rossetti’s poem The Goblin Market is the concept of the femme fatale. However, there are a few instances in the poem where Lizzie, the older sister, seems to possess some femme fatale-like qualities. In this post, I’ll examine how Rossetti’s definition of the femme fatale in her poem In an Artist’s Studio can be applied to Lizzie in The Goblin Market.

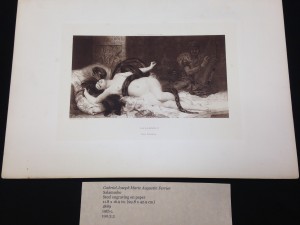

The term “femme fatale” was shaped by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the mid 19th century. Members of the group included artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who depicted a self-absorbed and beautiful femme fatale in his painting Lady Lilith, among others. And although Christina, Dante’s sister, was never officially a member of the Brotherhood, she played a crucial role within the group. Her poem In an Artist’s Studio was written in 1856. The poem references Dante’s art stuido and the many portraits of Elizabeth Siddal, the model for most of Dante’s work at the time.

In the poem, Rossetti notes how “one face looks out from all [Dante’s] canvases,” referring to the many portraits of Elizabeth Siddal. Through Dante’s paintings, Rossetti explains, Elizabeth can be depicted as anything, from “a queen in opal or ruby dress” to “a saint [or] an angel.” Now, the femme fatale, as defined on Merriam-Webster, is an attractive woman who causes trouble for the men who become involved with her. Dante spends all of his time and energy painting this one woman with “all her loveliness,” so Elizabeth must be at least somewhat attractive. Another line from Rossetti’s poem also hints that Dante is obsessed with Elizabeth: “he feeds upon her face by day and night.” The word ‘feed’ suggests that Elizabeth is Dante’s sustenance, in which case he physically cannot live without her and her beauty. At the end of the poem, Rossetti adds: “Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim; / Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright; / Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.” Rossetti explicitly states that “she” never waits for the man sorrowfully, but she did when he had hope, when she was in the man’s dream. This description precisely defines a female fatale, a beautiful woman who appears in a man’s dream but not in reality–at least, not for long periods of time.

Now, what if I told you Elizabeth Siddal’s nickname was Lizzie? Because it was. In fact, many articles refer to her as Lizzie, not Elizabeth.

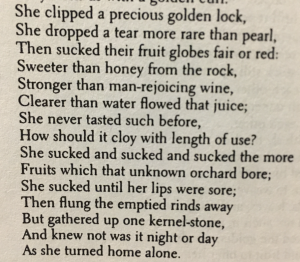

In The Goblin Market, Lizzie isn’t the traditional femme fatale. The poem states that her sister has golden curls, so presumably Lizzie does too, an attractive feature for a young woman. Similar to the face in the paintings, though, she doesn’t seek to cause trouble. However, when the goblins attack Lizzie, tearing her gown, soiling her stockings, stomping on her feet and trying to make her eat the fruit, she resists, ultimately annoying the goblins and causing them to give up instead of submitting to them like another more submissive woman might.

Are both of Rossetti’s characters modeled after Elizabeth Siddal? Perhaps, but more importantly, her definition of the femme fatale in her poem In an Artist’s Studio can also be applied to Lizzie in The Goblin Market, connecting the two poems.