After 24 years of data collection, a recently published study concludes climate change is affecting nocturnal bird migrations with serious potential consequences for bird populations.

According to the study, higher spring air temperatures caused as a result of global climate change, have resulted in a shift in the timing of migration events for thousands of bird species across the continental United States. The results have researchers concerned that some bird species might not be adapting to the climatic changes, which could fuel a decline in birds across the country.

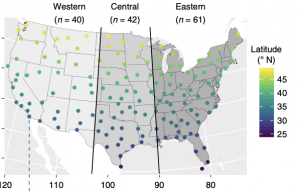

Above is a map of the Eastern, Central, and Western U.S. flyways. Each year in the Spring and Autumn, millions of migratory birds migrate through these flyways. (Map courtesy of (Horton et al. 2020)

The results were obtained by utilizing US weather surveillance radar (WSR). WSR is normally used to monitor the movement and development of storm systems, but due to advances in remote sensing technologies, the researchers were successfully able to utilize WSR to monitor nocturnal bird migrations. During the course of the study, which took place between 1995 and 2018, some 13 million radar scans were made across 143 radar sampling locations. The remote sensing technology enabled researchers to monitor nocturnal bird migrations in the western, central, and eastern flyways, which are the main migratory routes for most North American bird species.

According to the researchers, the data suggests “millions of migrating birds across thousands of species are migrating sooner in the Spring in correlation with warming surface air temperatures”. This has ornithologists worried that if species don’t adapt to the changing conditions, they will experience population declines.

Many bird’s species time their migration to the availability of resources such as food, water, and shelter. For instance, almost all birds rely on insects as a food source at some stage in their development, but if an insect dependent bird population arrives after the peak emergence of insects, then there may not be enough food to sustain that bird population. These types of scenarios are referred to as mismatches and they are becoming more common as a result of global climate change.

Despite what some may think, most birds actually migrate at night, when the temperature is cooler and predators are less active. These nocturnal migrants include most songbirds and waterfowl, as well as owls and some migratory shorebird species. These nocturnal migrants make up most of the bird populations within the continental United States.

Neotropical migrants are most at risk from climate change. Despite being the size of a human palm, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris), such as the one pictured above, crosses the Gulf of Mexico every year to get back and fourth from the United States. The hummingbird times its migration with the emergence of wildflowers and insects which makes up 100% of its diet.

Thankfully, ornithologists believe not all of these nocturnal migrants are at great risk. According to the study, birds that migrate shorter distances are less at risk of climatic induced mismatches. Scientist believe that birds who exhibit shorter migrations are more in tune to what’s happening across their range.

On the other hand, the study suggests that neotropical migrants, or birds that travel to the tropics and back each year, are most at risk. “A mismatch event for a neotropical migrant can be devastating” says professor Van Fleet, an ornithologist at Dickinson College in Carlisle Pennsylvania. That’s because these birds travel larger distances, and require substantially more energy to fuel their long migrations. If these birds arrive either to soon or to late they might starve to death.

As the climate begins to change at an ever-faster rate and in more unpredictable ways, the question seems to be how will birds keep up? Fortunately, the study found that at least some bird populations are migrating sooner in the spring and later in the autumn. These results do give a glimmer of hope for what the avian world may look like going forward.

References:

Horton, G. K., La Sorte, A. F., Sheldon, D., Lin, Tsung-Yu., Winner, K., Bernstein, G., Maji, S., Hochachka, M. W., and Farnsworth, A. 2020. Phenology of nocturnal avian migration has shifted at the continental scale. Nature Climate Change:10, pp 63-68.

Alex

"This title was very eye catching! That is so interesting that such a ..."

Alex

"This is really interesting! The fact that crops and plants are damaged is ..."

Alex

"Well done, this article is great and the information is very captivating! Ethics ..."

Alex

"I was intrigued throughout the whole article! This is such an interesting topic, ..."

Alex

"This is such an interesting article, and very relevant!! Great job at explaining ..."

Grandpa

"Honey You Did a good job I will forward to my eye doctor "

murphymv

"This article is fascinating because it delves into the details of the research ..."

murphymv

"I agree, adding the photo helped solidify the main finding. "

murphymv

"This is a fascinating finding. I hope this innovative approach to improving transplants ..."

Sherzilla

"This is a great article! I would really love to hear how exactly ..."

Sherzilla

"It's disappointment that these treatments were not very effective but hopefully other researchers ..."

Sherzilla

"I agree with your idea that we need to shift our focus to ..."

Sherzilla

"It's amazing to see how such an everyday household product such as ..."

Lauren Kageler

"I will be interested to see what the data looks like from the ..."

Lauren Kageler

"A very interesting article that emphasizes one of the many benefits that the ..."

maricha

"Great post! I had known about the plight of Little Browns, but I ..."

Sherzilla

"I assumed cancer patients were more at risk to the virus but I ..."

Sherzilla

"Great article! It sheds light on a topic that everyone is curious about. ..."

maricha

"This article is full of really important and relevant information! I really liked ..."

maricha

"Definitely a very newsworthy article! Nice job explaining the structure of the virus ..."

maricha

"It's interesting to think that humans aren't only species dealing with the global ..."

murphymv

"This is very interesting and well explained. I am not too familiar with ..."

Lauren Kageler

"Great article! This post is sure to be a useful resource for any ..."

Lauren Kageler

"Definitely seems like an odd pairing at first, but any step forward in ..."

murphymv

"What an interesting article! As you say, height and dementia seem unrelated at ..."

murphymv

"Great article! I learned several new methods of wildlife tracking. This seems like ..."

murphymv

"Very interesting topic! You explained cascade testing and its importance very well. I ..."

Alex

"This article is really interesting! What got me hooked right away was the ..."

Sabrina

"I found this article super interesting! It’s crazy how everyday products can cause ..."

Erin Heeschen

"I love the layout of this article; it's very eyecatching! The advancements of prosthetics ..."

murphymv

"Awesome article! I like the personality in the writing. Flash Graphene not only ..."

murphymv

"Very interesting work! I don't know a whole lot about genetics, but this ..."

Cami Meckley

"I think the idea of using virtual reality technology to better help prepare ..."

Erin Heeschen

"I wonder if there's a connection between tourist season and wildfires in the ..."

Ralph berezan

"Not bad Good work "

Michelle

"This sounds like it would be a great tool for medical students! ..."