Wildfire that broke out just outside Los Angeles in October 2019 forcing thousand to evacuate their homes. (Courtesy of CBS)

New study finds that plants may be up to twice as flammable when in their flowering and fruiting stages. According to researchers from Michigan State, the Climate Corporation, and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, plant phenology or lifecycle events influenced by climate, contribute to wildfire risk. The researchers concluded that the lifecycle stages of a plant can indicate wildfire risk and can be used to better inform wildfire management policies.

The study observed the phenology of Adenostoma fasciculatum an abundant species of plant in the Rose family known commonly as Chamise or Greasewood. A. fasciculatum is especially common in the area that surrounds Los Angeles and Santa Barbra where the study took place. This area also happens to be a breeding ground for wildfires.

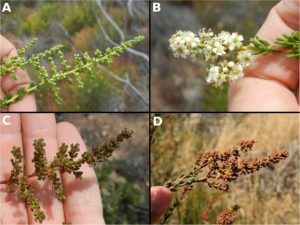

Photos of A. fasciculatum undergoing lifecycle changes: A) flowering buds B.) open flowers C.) developing fruit D.) ripe fruit (Keely et al. 2020)

Not surprisingly it was found that water content plays a leading role in determining plant ignitability, or the likelihood that a live plant will catch on fire. More significantly however, it was found that water content was less for A. fasciculatum during flowering and fruiting stages and thus is more likely to ignite during those lifecycle stages. This makes sense as A. fasciculatum begins to flower and fruit at the end of Spring and beginning of Summer which correlates to the start of the dry season for Santa Barbra and Los Angeles Counties.

Live Fuel Moisture (LFM) also plays a significant role in determining wildfire risks. LFM measures the ratio of water weight to dry tissue weight within an individual plant. Areas with lower LFM contents are likely to experience more intense fires that burn more land. Additionally, it just so happens that LFM is lowest for A. fasciculatum during the plants flowering and fruiting stages. When you put two and two together you get the idea that on a clear hot sunny day, it might be best to stay clear of the roses.

Due to the influence of LFM on fire danger, it has since been incorporated into the National Fire Danger Rating System (NFDRS) which quantifies the risks and severity of a potential wildfire occurring in a given area. In Los Angeles and Santa Barbra Counties, the United States Forest Service (USFS) has set an LFM threshold of 60-80% which indicates high fire danger and anything less than 60% as extreme fire danger.

Despite the correlation between plant phenology and LFM, other variables such as soil moisture, precipitation, and disease can also influence plant ignitability. Wild fires can break out at anytime when soil moisture content is low, temperatures are high, and when there are significant quantities of flammable debris around to be burned.

To better understand these relationships more studies will have to be conducted on the factors that increase live plant ignitability in A. fasciculatum. Additionally, such studies will have to be conducted on a far broader scale then two counties. Studies involving LFM and phenology on various plant species will also be important in terms of getting a more complete picture of live plant ignitability within different environments.

Going forward however, studies into plant phenology can reveal important aspects of how plants react to environmental conditions which can result in plant flammability and wildfire risk. Studying the relationship between the effects of LFM and plant phenology on live plant ignitability will be especially important in arid environments which are becoming increasingly dry and fire prone as a result of climate change.

References:

Nathan, E., Roth, K., and Pivovaroff, L. A. 2020. Flowering phenology indicates plant flammability in a dominant shrub species. Ecological Indicators 109.

Erin Heeschen

I wonder if there’s a connection between tourist season and wildfires in the area, especially with peak flowering at the end of spring and early summer… A dry season coupled with a probable increase in litter it doesn’t sound like a great combination.

Very interesting read!