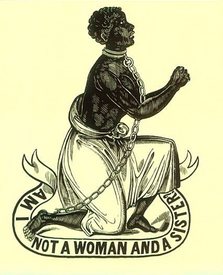

Mary Prince’s remarkable life story in “The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave” portrays her horrific treatment as a slave in the West Indies and her life-long journey towards freedom. Her simple, yet effective, writing style gives readers a glimpse into the heartbreaking reality of being a female slave in the early 1800s. Mary experienced the worst of slavery including severe physical abuse and being torn away from her family as a young girl, however her resilience and determination throughout these events is something to be admired. Mary told her life story with the goal of spreading awareness about the horrors of slavery in order to debunk common misconceptions about slavery held by many English people and ultimately implement change [1].

Mary was born into slavery in Devonshire Parish, Bermuda and spent the majority of her life enslaved to a number of different masters in the Caribbean, including in Turks and Caicos and Antigua. When she was about 40 years old (c.1828) Mary moved to London, England with her master in hopes of becoming a free woman. Due to the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which banned British involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, it was henceforth illegal for slaves to be carried on British ships [2]. Mary technically gained her freedom once landing in the United Kingdom, however her dependence on her master’s consent to maintain her freedom when returning to the West Indies combined with the fear of being in a new country resulted in her continuing to live as a slave for a number of years after arriving in London. The Slave Trade Act was passed with the idea of gradual emancipation and it was not until 1833 that a formal Emancipation Act was passed by Parliament [2]. Even then, the Act instilled a six-year apprenticeship system, in other words another form of gradual emancipation, that was not abolished until 1838 [2]. In 1828 if Mary were to return to the West Indies without proof of freedom she would most likely be forced back into slavery due to the laws of the time.

While the United States also banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, British colonies in the Caribbean had a greater dependence on the slave trade due to the high number of slave deaths that occurred [3]. In fact, the number of slave deaths was around one third greater in the Caribbean than the American South [4]. These deaths were common for a number of reasons including the harsh conditions of working on sugar plantations, the most common export of this area, disease, and malnutrition [5]. In addition, unlike in America, slaves were not increasing at the natural rate of reproduction due these large death tolls and the majority of imports being male [6].

Mary Prince’s narrative can be used as a basis of comparison between slavery in the British West Indies and the United States. One direct connection that can be made is the frequency in which slave families were separated. Mary was separated from her family when she was young and later separated from her husband, spending the majority of her life having to continually start over and form new relationships. While strong familial ties were evident in Mary’s narrative, stable slave families were more commonly formed on plantations in the United States than the Caribbean [7]. The mindset of plantation owners in the Caribbean was more focused on simply buying new slaves instead of encouraging those they had to form relationships and reproduce [5]. Despite not being able to legally marry in the United States many slaves started families and lived in constant fear of being separated from their loved ones [8]. Plantation owners made a lot of their money from selling their slaves, and around one third of enslaved children would experience some sort of separation from one and/or both of their parents at some point in their lives [8]. This familial separation was a great motivator to escape from slavery and become free in order to be reunited with ones family. Alternatively, if enslaved families were not separated, escaping from slavery would be quite difficult and they would be more likely to remain in slavery.

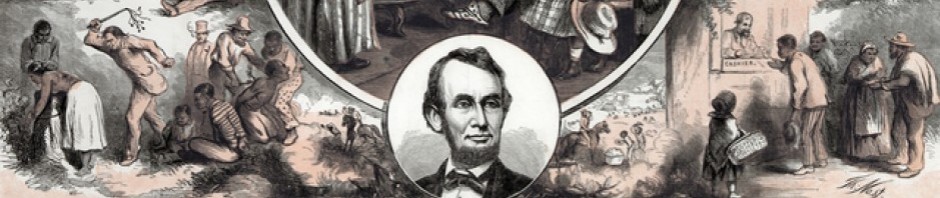

Mary’s narrative brought the brutality of slavery to those living in the United Kingdom and helped enlighten those who had previously been told that slaves in the West Indies and other British colonies were happy being enslaved. In the United Kingdom the West India Lobby was responsible for spreading propaganda about the benefits of slavery and claiming that enslaved people were happy with their current circumstances [2]. The West India Lobby benefitted greatly from the exports produced on slave plantations in the Caribbean, especially sugar, and wanted to prevent the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade from making progress [2]. To combat the efforts of pro-slavery groups the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, later the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823, helped to publish pamphlets and slave narratives, such as Mary Prince’s, and set up anti-slavery speeches and petitions throughout the country [9]. Similar to the publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” by Harriet Beecher Stowe in the United States in 1852, “The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave” exposed slavery for what is really was and allowed people to hear a slave’s perspective on slavery [10]. As Mary made quite clear in her narrative “All salves want to be free – to be free is very sweet” [11].

[1] Williamson, Jenn. “Summary of The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. With a Supplement by the Editor. To Which Is Added, the Narrative of Asa-Asa, a Captured African.” Documenting the American South. 2004. Accessed December 6, 2016.[http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/prince/summary.html].

[2] “The 1807 Act and Its Effects.” The Abolition Project. 2009. Accessed December 7, 2016. [http://abolition.e2bn.org/slavery_113.html].

[3] Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, 85.

[4] Mintz, Steven. “American Slavery in Comparative Perspective.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed December 7, 2016. [https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/origins-slavery/resources/american-slavery-comparative-perspective].

[5] Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, 90-91.

[6] Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, 84.

[7] Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery and the British Empire: From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, 98.

[8] Williams, Heather Andrea. “How Slavery Affected African American Families.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe. National Humanities Center. Accessed November 13, 2016. [http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1609-1865/essays/aafamilies. htm].

[9] Oldfield, John. “British Anti-Slavery.” BBC History. 2011. Accessed December 7, 2016. [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/antislavery_01.shtml].

[10] “Impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Slavery, and the Civil War.” The National and International Impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 2015. Accessed November 13, 2016. [https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/utc/impact.shtml].

[11] Prince, Mary. The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. With a Supplement by the Editor. To Which Is Added, The Narrative of Asa-Asa, A Captured African. Edited by Thomas Pringle. London: Published by F. Westley and A.H. Davis, Stationers’ Hall Court, 1831, 23.