The Newark Race Riots of 1967

By Nick Reese

“Local and state officials dreaded the approach of each ‘long, hot summer,’ as the rioting seasno became know. Riots broke out in dozens of cities in 1966 and in more than a hundred in 1967. Riots in Newark and Detroit in the latter year provided a grim counterpart to the summer of love in San Francisco” (H.W. Brands, H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States since 1945, page. 149).

Thomas Schettig was a 22 year old, newly wed husband and a father of two when he decided to join the Newark fire department in 1964. His decision to enroll as a volunteer firefighter came from his immense admiration for his father-in-law, Arthur Phillip Devlin, or known around the station as “Doc”. Doc was the fire department’s volunteer orthopedic surgeon who took young Schettig under his wing while they served together. The two volunteers paired up at the same station which was the company that was in charge of Newark’s inner city.[1] Schettig explained how the 1967 summer calls were routinely fires in the same communities.[2] “Doc and I were responding to a fire. The fires were in the predominantly black neighborhoods where they [the residents] were setting their own houses and buildings on fire.”[3] The tensions between the races had escalated to the point where firefighters were unsure of their safe return, not just from fires but also from the violence due to civil unrest. While historian H.W. Brands briefly describes the importance of the 1960’s riots role in race relations and civil rights in his book American Dreams: The United States since 1945,the actions that unfolded from these events influenced the civil rights and race relations.

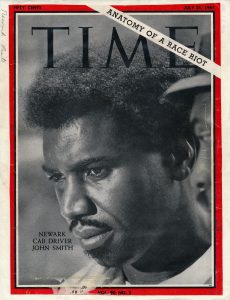

The beginning of the riots had started on July 12th when the Newark police had taken in a young black cabdriver by the name of John Smith into custody. [4] This was not an uncommon event, white police officers taking young black men into custody but with the recent deaths of the young black men Lester Long, Bernard Rich and Walter Mathis who all died in custody had the city on edge. [5] Newark was about to implode, it seemed the slightest misstep would do just that. The police have been repeatedly accused of abusing their power, especially on young African American men, when reports came out that John Smith was not only beaten but killed by the police, there was no fixing this problem. [6] Schettig remembers the fear of having to go out during these couple first days, “They had to respond because they were firemen and it did not matter where the fire was in the city of Newark, they had to go regardless.” [7] The situation escalated further when there was not a formal autopsy of John Smith’s body which brought bricks, bottles and molotov cocktails to the police precinct responsible for the man’s death.[8] All hell had broken out, the death of the young black cabdriver, John Smith, had finally ignited the Newark riot that seemed inevitable. The next upcoming days would change the city of Newark forever.

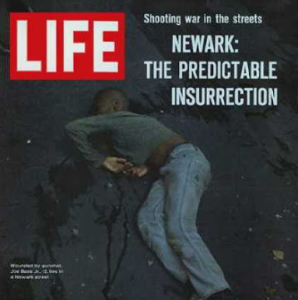

The current Mayor of Newark at the time, Hugh Addonizio, wanted to control the situation by publicly saying that the previous night had been an isolated insistent. [9] Though this did not seem to fix the problem, but only made everything worse. For the second straight night, a large crowd gathered to protest the same precinct, this lead to rioting and then the looting began. [10]. Around midnight on the second night, the looting had spread to Newark’s major commercial district in the ghetto. Mayor Addonizio gave police permission to use firearms to defend themselves.[11] The use of weapons by the police was matched by the civilians rioting with cheap guns and homemade weapons like molotov cocktails, zip guns, knifes, and creating fires.

During the 1950’s and the mid-1960’s “pipe guns’ or more for

pipe guns or more formally known as “zip guns” became popular in New York and New Jersey organized crime.[12] The use of these homemade guns were useful during the riots because of the simplicity of firing and

its large blast radius. [13]. Schettig recalls these homemade weapons and their sheer power, “They made a gun out of two pieces of pipe. I actually fired one of them. You take two pieces of pipe, six to eight inches long, and then you get a second piece of pipe that is one size bigger than the first. The smaller pipe holds the 12 gauge shotgun shell. You would insert the shotgun shell into the small pipe and then on the bigger pipe, its threaded, you put a cap on the end and then put a screw through [the cap] and thats your firing pin. When you yank the two together it discharges a round, and I fired one [of these pipe guns] into a wall in the basement of the of the rescue squad building. I had the pipe up against the wall and i banged it. That damn thing about an 18 inch circular pattern of the shotgun shell. For about two dollars you could make a weapon, they used these [guns] during the riots.[14]

This “Urban warfare” as Brands describes it, had needed the national guard to bring peace to the city. The warfare that is briefly discussed in American Dreams: The United States since 1945, but it does not give enough justice to the sheer chaos that the city experienced. Schettig recalls, “One of the only nights I was there for the riots was when we [the firefighter squad] were being shot at while trying to put out a fire.”[15] Brands brings more clarity to why rioters were shooting at Schettig, “Snipers, presumably black, targeted the mostly white emergency and police personnel,” which Brands explains how “[this was] provoking the police and their national guard reinforcements, also predominantly white, to fire almost indiscriminately on looters, suspected looters, and anyone who looked suspicious.”[16] The violence had allowed for police and the national guard to open fire on anyone that they saw fit, which put Schettig and Doc in even more danger. The fires and violence at this point had become too big to contain.

“While the people were shooting at us, we hid under the firetruck. The shot wasn’t aimed at me, but the shots were in our direction. Once the shooting stopped, we got the hell out of there because all of us in the squadron had a family. I was just a couple years older than you with two kids and a wife at home. I never told your grandmother about this because I needed to support my family and I really looked up to your great grandfather.”[17]. Like many other white residents in Newark, Schettig left after the race riots of 1967 because he did not feel like his family was safe to grow up there. The importance of Newark in the early and mid 19th century was immense. Newark acted as a commerce and manufacturing outlet that was close to New York City as well as had major harbors and an airport.[18] The “white-flight” had decimated the city and its previous importance, the significance of the 1967 riot had crippled Newark’s economy and caused the crime and corruption to increase dramatically.[19] Relocation of many white residents out of the hearts of many American cities resulted in what happened to Newark. The economic implications were obvious but the divide between America’s races became deeper. The race riot showed the clear division between white Americans and black Americans.

H.W. Brands’s description of the Newark riot gives an explanation on how the racial tensions became worse but he does not express the pain that it caused so many families, black and white. The fear created in Newark, Watts, and Detroit changed the cities as well as the people in them. The riots were so powerful in changing race relations are seen today. It took the destruction of cities to see how the divides were in America. Schettig still shivers at the thought of those nights, “One of the nights of the riots, Doc had a fireman die in his arms.” Schettig paused and signed. “He bled to death trying to save someone out of a burning building.” [20]

“I couldn’t. I just could not and would not tell my wife. If she knew how much danger I was in that night and how much danger her father was, I do not think she would ever forgive either of us.” [21]

Interview Subject

Thomas Schettig, age 72, retired small business owner who graduated from Saint Francis University and Penn State University and is a retired Newark volunteer firefighter during the 1967 race riot.

Interview

-Audio Recording, Carlisle, PA, April 1, 2017

Selected Transcript

Q. When you were a volunteer firefighter with Doc. [Great Grandfather] what were some of the incidents you remember about the race riots in 1967? When did the things seem to go wrong that started these riots?

A. I was there for the riots as a matter of fact. That was when they had the tanks coming up from the National Guard on Springfield Avenue.

Q. Why did they bring the tanks into Newark?

A. It was because the people [citizens of Newark] were rioting. The rioting started because of the raised tensions of between the Black and White communities. At this time most of Newark had become black and the start of the riots on a hot summer night in 1967, many people were sitting around drinking and one thing led to another and people began to riot. I know one of the nights your great grandfather had a fireman die in his arms.

Q. What happened [With great grandfather]?

A. He [firefighter] was climbing up a ladder to stop a fire from one of the riots but while in the process, he was shot in the back by an unknown assailant. He [firefigher] bled to death in about two minutes in Doc’s arms.

Q. In Newark, were these riots the result of the city being segregated? Were the riots in the predominantly black neighborhoods or were they in the predominantly white neighborhoods?

A. They [African Americans citizens of Newark] rioted and burned down basically burned down their own homes and buildings. Many of their homes in these neighborhoods were government own homes. These homes were called scudder homes which they [residents of the homes] burned them down in an act of protest. They would rip all of the copper piping out of the houses before they burned them down because they could sell it for scraps .

Q. Were the riots the white communities vs. the black communities? Why were there not more riots in the white communities of Newark?

A. There was not a lot of violence in the white communities, especially in one area called the North Ward. Black people were afraid to go there [North Ward] because of a guy by the name of Anthony Imperiale, who was one of the local councilmen, and he didn’t take any crap from anybody. One day his mother was molested and mugged by an African American man and I don’t if they killed him or if they found him and beat the man to death. So after that, African Americans were afraid to go to the North Ward. I can still see him [Councilman Imperiale] driving around in his old black car with the flags on it and nobody messed around in the North Ward that was black, nobody.

Q. What was the view towards African Americans before and during the riots?

A. The view towards African Americans during this time were the impression that they [African Americans] were uneducated, childish, and liked to drink. This is the stuff that they do not teach you in school, this was not right how they were perceived but this was just the stigma of the time period because this would be, from what I understand, politically incorrect. This is how we were taught to perceive them back then.

I’ll tell you another story that a policeman told me, they [African American residents] were rioting on sunset avenue, they were looting a tv store. And the one cop had a Thompson submachine gun, with gun, and they were shooting people. The guy [assailant] reached and stole a tv set and the cop said “that was a big guy and I ran after him into a building” and he [the police officer] said “I was not more than two seconds behind him and I jumped into that doorway and I open fired. By the time I stopped firing, there was nobody in the hallway.” I heard the story from that cop.

And then, during this time period, African Americans could not afford guns so they made a gun out of two pieces of pipe. I actually fired one of them. You take two pieces of pipe, six to eight inches long, and then you get a second piece of pipe that is one size bigger than the first. The smaller pipe holds the 12 gauge shotgun shell. You would insert the shotgun shell into the small pipe and then on the bigger pipe, its threaded, you put a cap on the end and then put a screw through [the cap] and thats your firing pin. When you yank the two together it discharges a round, and I fired one [of these pipe guns] into a wall in the basement of the of the rescue squad building. I had the pipe up against the wall and i banged it. That damn thing about an 18 inch circular pattern of the shotgun shell. For about two dollars you could make a weapon, they used these [guns] during the riots.

Q. Can you tell me more about the riots from your experience?

A. One of the only nights I was there for the riots was when we [the firefighter squad] were being shot at while trying to put out a fire. While the people were shooting at us, we hid under the firetruck. The shot wasn’t aimed at me, but the shots were in our direction. Once the shooting stopped, we got the hell out of there because all of us in the squadron had a family. I was just a couple years older than you with two kids and a wife at home. I never told your grandmother about this because I needed to support my family and I really looked up to your great grandfather [my grandmother’s father].

Q. During the night of that particular riot, what was the call that you and Doc were responding to?

A. Doc and I were responding to a fire. The fire was in one of the predominantly black neighborhoods where they [the residents] were setting their own houses and buildings on fire.

Q. Did the fire station have to respond even if they knew that the fire was because of the rioting?

A. They had to respond because they were firemen and it did not matter where the fire was in the city of Newark, they had to go regardless.

-Audio Recording, Carlisle, PA, April 25, 2017

Selected Transcript

[Q] Can you tell me about the emotions you were feeling during those for days in July 1967.

[A] I was terrified for my family because the night I went out people were shooting in our direction. I wasn’t sure If I would make it home. One of the nights of the riots, your great grandfather had a fireman die in his arms. He bled to death trying to save someone out of a burning building.

[Q] Can you tell me more about why you didn’t tell your wife about your involvement in the riot?

[A] I couldn’t. I just could not and would not tell my wife. If she knew how much danger I was in that night and how much danger her father was, I do not think she would ever forgive either of us.

WorkCited:

[1]- Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[2]- Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[3] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[4] – Herman, Max Arthur. 2013. Summer of Rage : An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots. New York: Peter Lang AG, 2013. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed April 28, 2017).

[5] – Herman, Max Arthur. 2013. Summer of Rage : An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots. New York: Peter Lang AG, 2013. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed April 28, 2017).

[6] – Herman, Max Arthur. 2013. Summer of Rage : An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots. New York: Peter Lang AG, 2013. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed April 28, 2017).

[7] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[8]- Herman, Max Arthur. 2013. Summer of Rage : An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots. New York: Peter Lang AG, 2013. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed April 28, 2017).

[9]- “Newark Riot (1967) | The Black Past: Remembered And Reclaimed”. 2017. Blackpast.Org. Accessed May 1 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/newark-riot-1967.

[10] – “Newark Riot (1967) | The Black Past: Remembered And Reclaimed”. 2017. Blackpast.Org. Accessed May 1 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/newark-riot-1967.

[11] – [8 -11]”Newark Riot (1967) | The Black Past: Remembered And Reclaimed”. 2017. Blackpast.Org. Accessed May 1 2017. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/newark-riot-1967.

[12]- Goldstein, Joseph. 1364. “The Very Brief Revival Of The Homemade Zip Gun”. City Room. Accessed April 28 2017. https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/02/the-very-brief-revival-of-the-homemade-zip-gun/?smid=tw-nytmetro.

[13] – Carter, Gregg Lee. ABC-CLIO. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Cremona , CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012.

[14] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[15] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[16] – H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 149 – 150.

[17] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (first recorded phone conversation), April 1, 2017.

[18] – NOAH, ADAMS. “Profile: Newark, New Jersey, upgrades its trolleys.” All Things Considered (NPR) (n.d.): Newspaper Source Plus, EBSCOhost (accessed April 28, 2017).

[19]- NOAH, ADAMS. “Profile: Newark, New Jersey, upgrades its trolleys.” All Things Considered (NPR) (n.d.): Newspaper Source Plus, EBSCOhost (accessed May 29, 2017).

[20] – Interview with Thomas Schettig (second recorded phone conversation), April 25, 2017.

[Fig. 1] – 2017. Img.Timeinc.Net. Accessed May 1 2017. http://img.timeinc.net/time/magazine/archi

[Fig 2] – 2017. S-Media-Cache-Ak0.Pinimg.Com. Accessed May 1 2017. https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/04/eb/9f/04eb9fab6ebdd089ad031f81fe5b8e8b.jpg.

[Fig 3] – 2017. 2.Bp.Blogspot.Com. Accessed May 1 2017. http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-DonwzxyZFC0/U2URsITGS8I/AAAAAAAADWI/9RkZFZ-SuSA/s1600/41372349-SS_Americas_Most_Destructive_Riots_Newark_1967.jpg.

[Fig4] – 2017. Whowhatwhy.Org. Accessed May 1 2017. http://whowhatwhy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/123-26.png.

Leave a Reply