If I had one goal for my work at the Cumberland Historical Society, it was to prioritize and increase my effectiveness. The biggest roadblock I had run into in my past research efforts had been my affinity for overextending myself. This time, I wanted to focus my attention and efforts on one topic and truly explore that as far as I could. This led me to answer the question of education. In my Ancestry research, I had noticed a trend among the Spradleys.

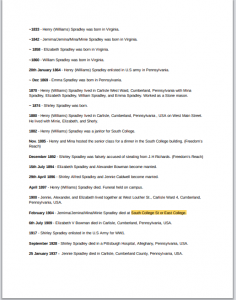

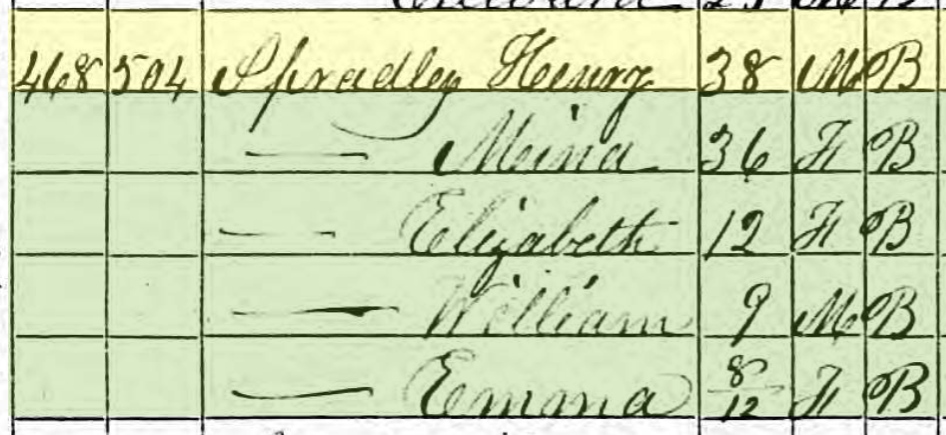

In the 1870 Census, Henry (Williams) Spradley was identified as being able to read, but unable to write. There’s some discrepancy, then, in the 1880 Census, as it identifies him as unable to read and write. In both the 1870 and 1880 Census, Mina is identified as unable to read or write. Compare this to their children; William and Elizabeth are identified as recently attending school in 1870, and Shirley is identified as being able to read and write in the 1900 census. This difference over generation made me think about the increased access to education post-enslavement, and to wonder how that took place in Carlisle specifically. With almost no knowledge of the Carlisle school system, I decided to dive head-first.

Thanks to the work of Professor Pinsker, I was provided with a list of relevant primary and secondary sources about Black communities in Carlisle in the late 19th century. My first step, therefore, was to read these sources in order to find more direction when I arrived at the Historical Society. In hindsight, this work would have been better done on campus, during the hours that the Historical Society was closed, but I didn’t have that foresight. Instead, I read over these contextual documents in the Historical Society library, which left me with less time to search in the library itself. That’s a mistake I’ll certainly learn from.

I found a lot of important information in the contextual readings. The 1896 article; “Negroes Under Northern Conditions” by Guy Carleton Lee, was greatly useful in creating a general understanding of the education system in Carlisle. In this source, I read an introduction to the separate school system created for Black children.

The author, Guy Carleton Lee, cited records of the Carlisle School Board. I was quick to jot that down and figured the Historical Society would have some resources from the School Board.

This being my third research attempt on the Spradleys, I knew better than to expect to find an exact record of Shirley, William, Elizabeth, or Emma. But I knew I could at least paint a picture of their time, enough to suppose the conditions they encountered.

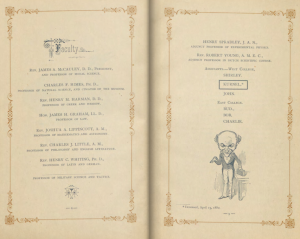

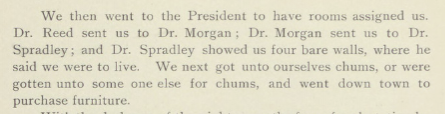

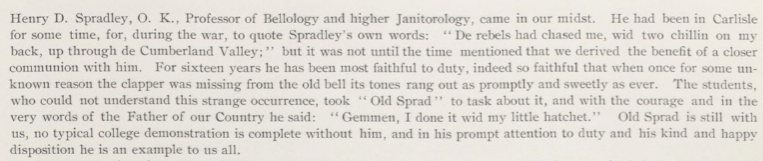

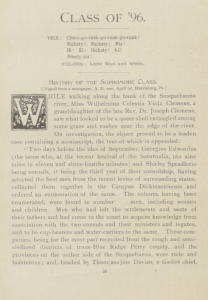

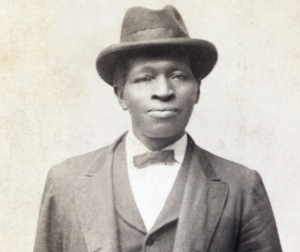

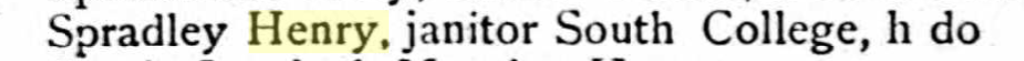

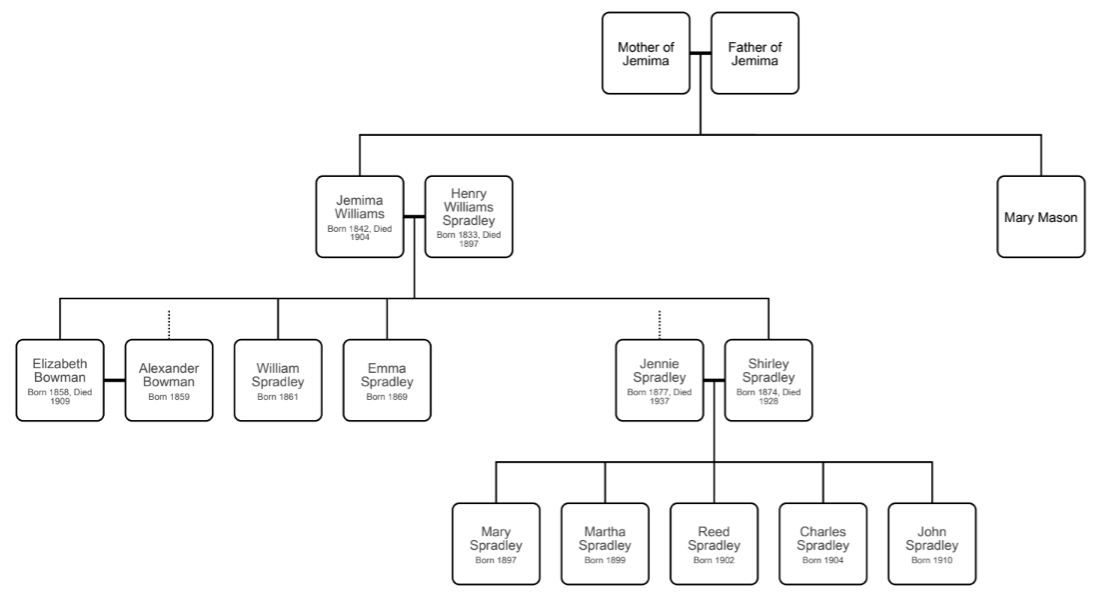

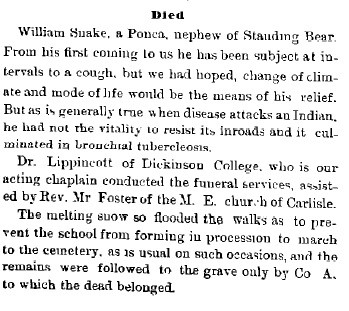

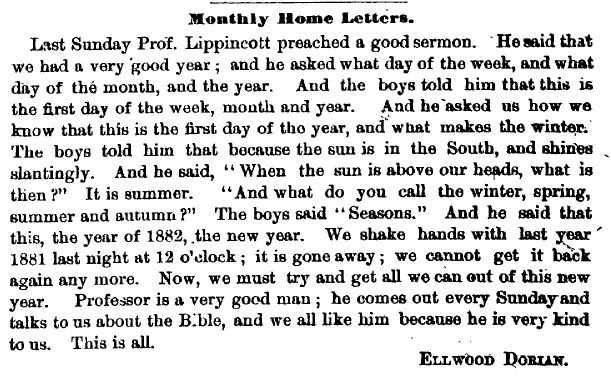

Specifically, after conversations with Professor Pinsker, I wanted to know when the separate schools were created, and if there had ever been integrated classes pre-official integration. This topic veered off from the Spradleys and towards the story of the Youngs; the story of fellow janitor Robert Young’s fight to have his son (Robert G. Young) admitted to Dickinson in the 1880s. Newspaper articles reporting on the case had interestingly identified Robert G.’s classes as being integrated, which directly conflicted with the widely understood timeline of integration. If I could answer this question as well, I’d be pleased.

I used the Historical Society’s Past Perfect search database next. The database was slow, especially compared to Ancestry and the Dickinson Archives, so this was another opportunity to be careful budgeting my time. I searched “colored school”, “school board”, “Carlisle schools”, and “Black school.” From those searches, I found a good amount of sources.

The first thing that caught my eye was “Carlisle School System Records, 1836-1935.” This was the perfect, primary source material I was looking for to describe the schools and maybe even list the students. Next, I found the “Development of Colored Education,” another source developed by the Carlisle School System. I found a large number of secondary sources that recounted the Carlisle schools, including Thomas Vale’s “A Century of Progress” (c. 1934) and “Mary E. Brown vs Carlisle School Board” by David Strausbaugh (c.1985.)

Satisfied with my results, I requested the items and went through them one by one. By reading all the sources, I was able to construct a rough timeline of the school system.

I learned that the “colored school” was founded in 1836, along with the rest of the school system. As the need grew, additional schools were opened in 1864, 1878, 1882, and 1892. [1]

I had hoped to find some building plans or photos included in the school board’s notes, but unfortunately, I had no such luck. I used PastPerfect again, using similar search terms, but the photos that turned up were few. I spent a lot of time trying to download the images to my computer, so that I could retain their quality, but too late into the process, realized that was a poor use of my time.

Generally, I learned a lot about the culture around these “colored schools” because of their marked absence from many documents. These schools, in every way, were afterthoughts in budgeting and public memory keeping.

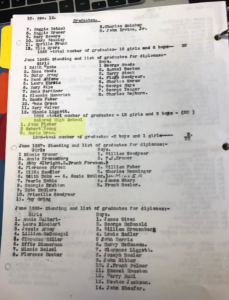

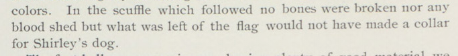

The most useful source I found was “Development of Colored Education,” an abridged version of the school board’s notes. This collection of notes specified the exact dates schools were founded, but rarely their full addresses or building details. The most exciting part of this source was absolutely the list of student graduates (from the regular schools and the “colored” ones.) Once I realized I could find the Spradley children among these names, I became very excited.

While I understood the “colored schools” were much smaller than the mainstream ones, I was still surprised at how few graduates were produced. Guy Carleton Lee attributed this to a “lack of parental co-operation”, or in other words, Black parents were too busy at work to help their children in school. [2] I can’t say whether or not this was true, but unfortunately, it seems the Spradley children may have been part of this trend of failing to graduate.

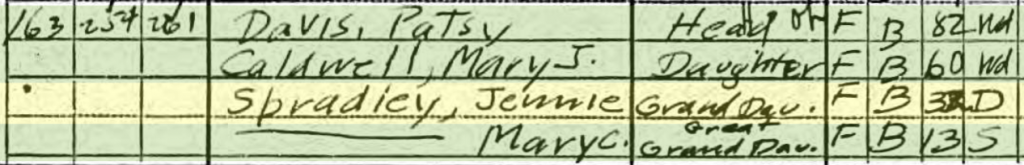

Doing some simple math, I found roughly the years I could expect the Spradley children to be enrolled. As of the 1870 census, Elizabeth and William had been recently enrolled, and Shirley was literate by age 22 in 1900. This was a window of 30 years, but even so, there were no traces of any of them.

I felt defeated by this discovery. I had been so excited by the idea of finding them recorded in the school system notes that I didn’t know what to do once I had failed. Then, I realized, I had yet to answer the question of Robert Young’s son, Robert G., and the mysteriously integrated schools.

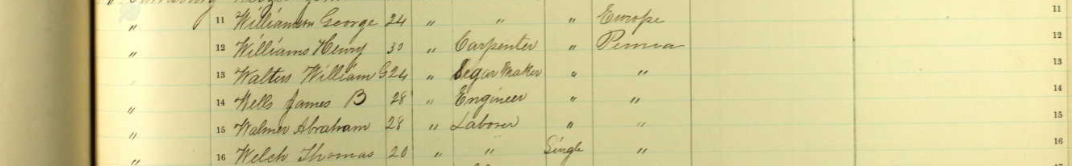

I went to the Freedom’s Legacy website, and refreshed myself with the story of Robert G. According to an October 1886 article, Robert G. had “graduated from the High School… among a large class of white and colored students.” [3] Armed with the student rosters, I went searching for Robert’s name.

I found it under June 1886. There his name was listed; “Robert Young” under the header “Colored High School.” Above, were listed the white male graduates. This evidence, paired with the school board notes cited above, I believe, puts the mystery to rest. Schools were in fact still segregated as of 1886, and newspapers were using the term “class” to describe the entire graduating class, as opposed to the specific school.

My time in the Historical Society was running out, so after searching for photos one last time, I called it quits. I hadn’t accomplished everything I had set out to do, but I found some answers to other questions along the way. Furthermore, I discovered a more complicated story of Black education than I had previously known. Maybe we’ll never find answers to the questions about where and when the Spradley children attended school, but we do now know that education was highly controversial, and even when schools were available, they didn’t always support their students as best as they could.

Lessons Learned and Loose Ends

I wish I had had more developed knowledge of Carlisle geography, as that could have helped me greatly in guessing where the schools may have been and conducting more research.

Greater access to School Board information could have been useful as well, especially as there were references to incident reports in the “Negroes in Northern Conditions” piece that could not be found in the notes available at the Historical Society.

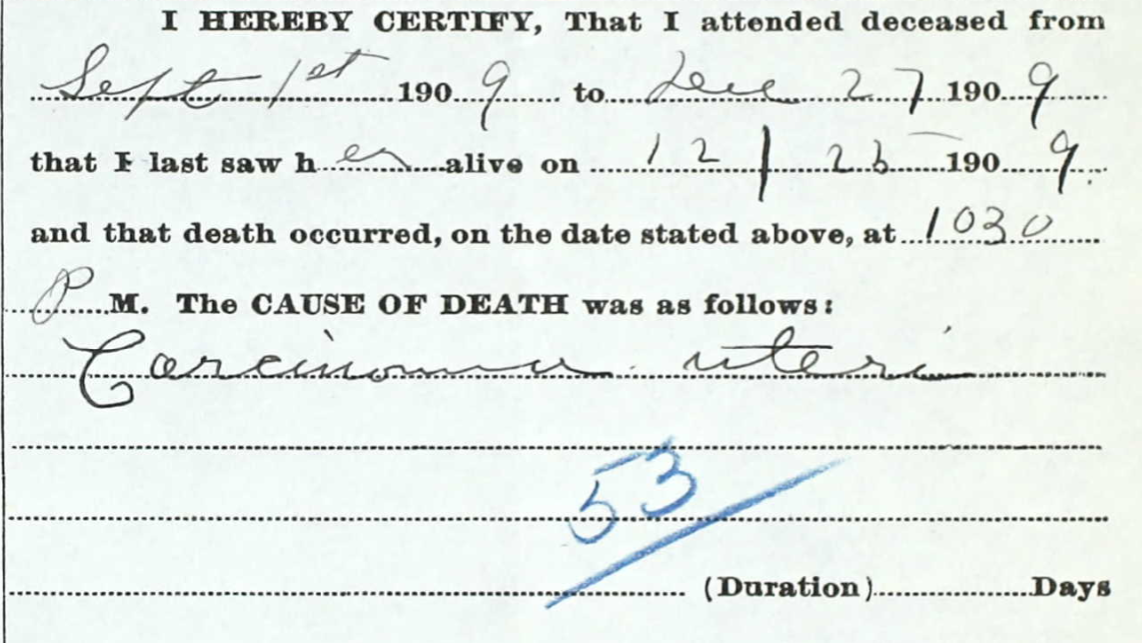

There is more work to be done on the Spradley family, but an interesting lead I noticed was Henry being identified as disabled in 1870 and 1880, and Mina in the 1870 census. The causes of these identifications may be available through newspapers if they had been the result of accidents or something similar. Furthermore, I’d be interested to see how this ties into the greater white impression of disabilities in Black populations, pre, and post-slavery.

I learned a good deal about archival research, especially when it came to using secondary sources that summarized events. I knew they were good jumping points, but that there was always a bias or motive driving the creation of the work.

[1] Lee, Guy Carleton. “Negroes Under Northern Conditions.” Gunton’s Magazine 10 (January 1896): 61–62.

[2] Lee, Guy Carleton. “Negroes Under Northern Conditions.” Gunton’s Magazine 10 (January 1896): 62.

[3] “Kept Out of College,” Philadelphia Times, October 20 1886, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/slavery/files/2018/10/Screen-Shot-2018-10-10-at-1.33.04-PM.png)