We talk a lot about process here at the Writing Center, but what exactly does that mean? The process of writing is just transferring information from your brain into squiggly marks on a screen that then turn into information in someone else’s brain, right? Well…

If you signed up today to run a marathon in three months, you’d probably do some things to prepare. You might buy some good running shoes…and if you did, you’d have to break them in before setting out on a run….and if you weren’t used to running, you might start by walking every day and then adding in some light jogging… and you might ask a friend to join you to keep you motivated… then you might join a running club to start getting into the habit of extending your pace etc. Oh, and you’d definitely curate a running play-list!

The point is, there is a lot that goes into running a marathon that you don’t see the day of the race (and without all of that, the race itself would be even more painful that it already is!) Writing is the same. We spend so much time looking at the final product (literature, journal essays, polished speeches) that we don’t always acknowledge the messy stuff that goes into creating that product.

The good news is that the Writing Process doesn’t involve getting up before the sun rises (I mean, it can, you do you) and forcing yourself to get on the treadmill or brave the elements. We tend to break down the things that happen before a piece of writing materializes on your screen into a couple of different stages. And I will admit, they do take time and effort:

The first stage we talk about is invention, in other words, coming up with an idea. That idea usually (always) changes and evolves and slips away from you and morphs into something totally different, but there is always a moment when you say to yourself some version of “what am I going to write about?” Sometimes it takes a loooong time to answer that question for the first time. And just because we name it first doesn’t mean it really comes first– you might find that you can only get to that moment by experimenting with writing down some ideas or doing some pre-writing.

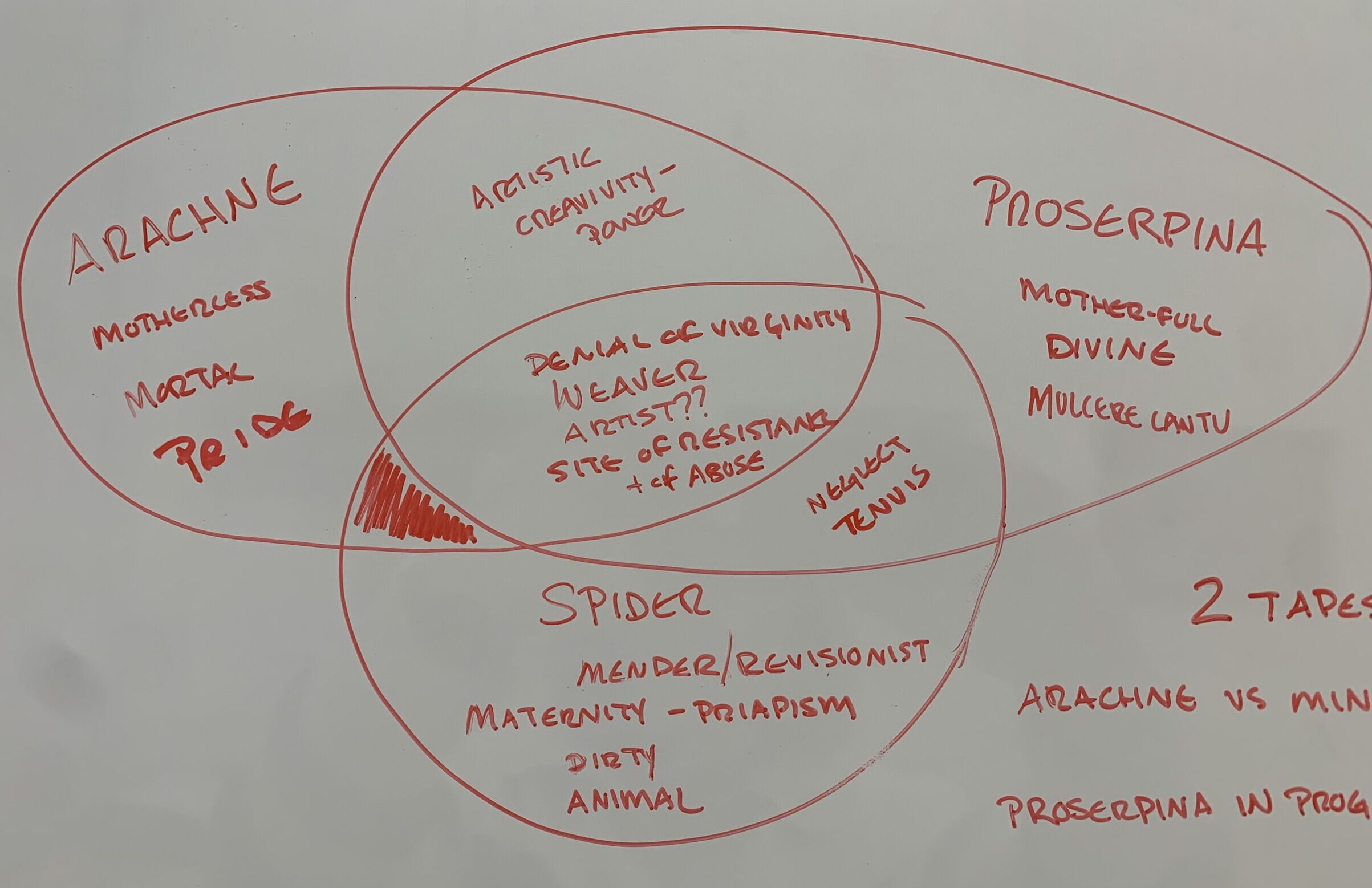

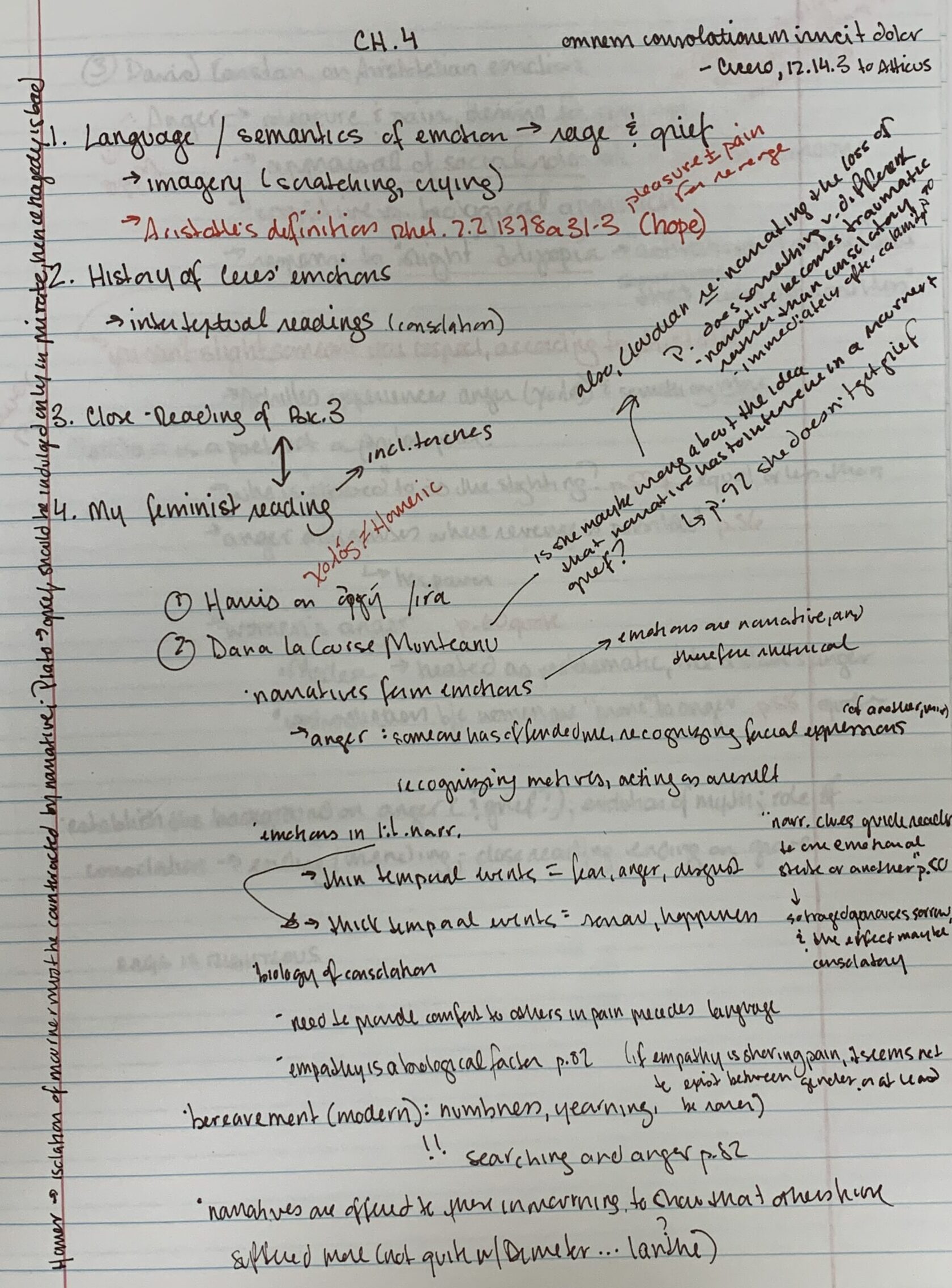

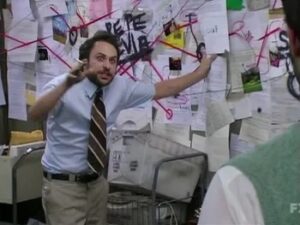

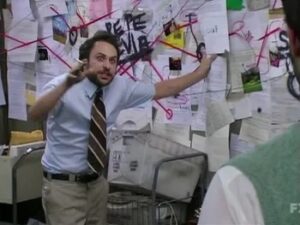

Pre-writing is the wacky stuff. This is the brainstorming, the word mapping, the annotations and highlighting on a text, the conversation with your mom at 7pm (or your roommate at 2am) about the assignment. It’s the outlining and the half finished sentences that might work but might not. Usually it looks something like this:

The shitty first draft is an integral part of the writing process, absolutely 100% as important as the thing you turn in. Crucially, it is not the thing you turn it. Anne Lamott describes it as ” the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later.” Call it what you like, shitty first draft, stream of consciousness, free-writing– the main thing is that at this stage you have to make an agreement with yourself not to “edit as you go”. You’ve got to look yourself in the eye and say, “You can write whatever you want, I won’t judge you.”

A lot of us never give ourselves permission to just write without adding another word or phrase to the sentence (“I have to write beautifully/enough that I have something to turn in by midnight/intelligently/without showing that I really don’t know anything about this topic/well enough to get an A on this essay”). Try it out. Because once you write a draft without judgement, you have something to work with, something to revise.

Revision is not, as a lot of us have been taught, fixing word choice and double-checking grammar (that, along with formatting, is editing). Revision is rewriting. This is when you look at that shitty first draft and say to yourself, “Good job. Now lets see what we can do with this.” Revision involves asking lots of questions, trying out different things (different words and phrases, yes, but also maybe a different organization, a different angle, maybe even a different answer to the main question).

Because of the nature of a screen, these stages of writing are presented as a list that looks chronological: we start with invention, we do some pre-writing, we draft, we revise, then we edit. In reality, writing resists that sort of linear cleanliness. Writing is messy, there’s nothing clean or linear about it. It’s more of a Mobius strip than anything else. There’s no right or wrong place to start (well, the wrong place to start is the one that prevents you from moving freely through your ideas) and more likely than not, the “pre-writing” is something you’ll return to again and again.

These are phrases that will probably occur in later blog posts. The key take away is that writing is a lot more than translating information from one brain to another via words on a page. Stay tuned for next week’s Writing Studio blog post: how to brainstorm and why!