by Seth Levin

The movie Hannibal (1959) is a dramatic recreation of the Second Punic War, fought between the two great empires of Rome and Carthage. As the movie begins, viewers are thrown into the midst of Hannibal’s (Victor Mature) Carthaginian army—consisting of soldiers, pack animals, horses, and deadly war elephants—crossing of the Alps, an immense feat,. This spectacle is not downplayed, as Hannibal’s troops are shown marching up steep mountain cliffs, trying to maintain control of their horses and elephants while hindered by the freezing cold. Throughout the entire crossing, Hannibal’s officers relentlessly order the soldiers to “keep marching,” even though some have fallen off the mountain, or been pushed by the horses and elephants. Eventually, Hannibal reaches the summit of the mountain; Maharbal (Franco Silva), Hannibal’s cavalry commander, exclaims “Hannibal! The rations are all gone! The men are freezing to death” and demands that Hannibal “relieve me of my command” (14:50). After their conversation, Hannibal gets word that a barbarian leader and his men, who control the opposite side of the Alps “are surrendering” and that their leader Rutarius (Bud Spencer) “has come down to negotiate” (15:43). Hannibal and Rutarius have a brief conversation in which they make a truce that allows Hannibal to descend the Alps into Italy, while Rutarius is guaranteed supremacy over the region where his tribe lives.

After Hannibal descends out of the Alps, he sets up camp near the Trebia. Here, Mago (Mirko Ellis), one of Hannibal’s brothers, brings a Roman slave into Hannibal’s tent who has information about an important hostage. At first, Hannibal is uninterested, and decides to send him away. Then, the slave urgently exclaims, “I threw myself at the mercy of the all-powerful Hannibal, liberator of the oppressed” and tells Hannibal that the hostage is Sylvia (Rita Gam) “the niece of Fabius Maximus” (Gabriele Ferzetti) (25:23). After the slave discusses the location of Sylvia, Hannibal ambushes her and Quintilius (Terence Hill), who is her childhood friend, bodyguard, and son of Fabius Maximus. During the ambush, Sylvia goes into a cave to hide from Hannibal. Once Hannibal finds her, Sylvia, not knowing who he is, pleads to “let me and the boy go free” and that if he should “my uncle would pay you very well for delivering us from Hannibal; he could even appoint you officer in one of our legions” (28:35). Not falling for the bribe, Hannibal escorts both of them back to his camp.

Back at his camp, Hannibal locks Quintilius in a cage and invites Sylvia to join him in a tour of his camp, as he was stricken by her beauty when he first caught a glimpse of her. While escorting her around his camp, he stops at a vantage point where they can see all of his ally reinforcements and afterwards, Hannibal shows her his elephants, which leaves Sylvia awestruck. At the end of their tour, Hannibal tells Sylvia that “I want you to take a message to your uncle. Tell him that Hannibal seeks peace” (33:48). Sylvia is skeptical towards Hannibal’s notion of peace, but Hannibal reassures her that “The Carthaginians always wanted peace” (34:07). The next morning, he frees Sylvia and Quintilius and allows them to travel back to Rome.

Once Sylvia and Quintilius make it back to Rome, Fabius Maximus assures her that she misunderstood Hannibal’s claims for peace, and that it was not peace which led Hannibal to release Sylvia, but his intentions of intimidating Rome. Fabius then goes to the Senate and devises a plan to “tire him, wear him down with skirmishes. Ambush his vanguards. Each day, each hour that passes is another arrow for our bows!” (38:50). The Senate laughs at his proposal and instead decides to attack Hannibal head-on at the Trebia, a plan devised by an unamed Roman senator played by Renzo Cesana.

After the Senate discussion, the movie quickly shifts towards the Battle of the Trebia, where the Roman army first sees Hannibal’s mighty elephants. During the battle, Roman soldiers are trampled by the elephants and some are even picked up by the elephant’s trunks and thrown around the battlefield. In the closing stages of the battle, a Roman centurion shouts “we can’t hurt these animals! Fall back men!” (40:55). At the river, the Carthaginian army successfully defends their camp against the Romans who are attempting to sail across on makeshift rafts. The Trebia scene however, is mostly dedicated to showing off the might of Hannibal’s elephants, and is unusually short for being the first major battle in the Second Punic War. Following this victory, Hannibal begins to lose sight in his right eye.

Soon after the battle, Fabius discovers that Flaminius has been replaced as commander. Outraged by this decision, Fabius declares that he will “no longer support with my presence” the decisions the Senate makes (44:51). Fabius leaves the Senate. Meanwhile, Sylvia goes back to Hannibal to try to negotiate peace. However, when she arrives at Hannibal’s camp, she discovers that Hannibal does not want to make peace with the Rome, leading her to ask him “Why did you send for me now?” Hannibal replies “Because I wanted to see you, and I hoped you wanted to see me” (51:36). Quintilius then arrives with a plethora of men and begins to attack Hannibal and some of his horsemen. Eventually, after a lackluster and unrealistic battle scene, Hannibal spares Quintilius and Sylvia yet again and sends them back to Rome.

Once they arrive in Rome, Fabius is appalled that Sylvia went back to see Hannibal and betrayed Rome; he sentences her to live out her years in confinement in the Temple of Vesta. The day before her confinement is to begin, Sylvia’s maid brings her good news that “Hannibal has found out; he loves you Sylvia! Hannibal wants you to come to him! He is waiting for you, he loves you!” (57:30). Sylvia flees from Rome, planning to defect to the Carthaginian side for the rest of her days. Meanwhile, the Senate holds a meeting and elects Varro (Andrea Aureli) and Aemilius (Andrea Fantasia) as consuls.

Before the Battle of Cannae, Maharbal plans to murder Sylvia because he believes “that girl will be the ruin of us” (59:05). Hasdrubal tries to placate Maharbal by telling him “there is no woman alive who can influence Hannibal.” But Maharbal replies, “No? Then explain to me why he uses every possible reason to avoid combat?” (1:01:20). In an act of mutiny, Maharbal leaves the gates of the elephant corral open, allowing them to run wild inside the camp. Hannibal bravely saves Sylvia from the elephants and soon after discovers that Maharbal was behind the plot. As a result, Hannibal battles Maharbal until Maharbal eventually loses due to Hannibal’s skill in combat. Hannibal lets him live, stating that “if I didn’t need you I’d…[kill you]” (1:05:40).

After Maharbal’s failed mutiny, the Roman army begins to advance on Hannibal’s encampment near Cannae. Hannibal’s strategy is to deceive the Romans in order to surround them in a pincer formation. He plans to send a small infantry unit out into the field and once they see the Roman army, pretend to retreat, thus drawing the Romans closer to the Carthaginian camp. Then, Hannibal plans for two cavalry units to flank the Roman army from behind, trapping the Romans on all sides. Varro and Aemilius argue about the best way to attack the Carthaginians. Aemilius rides up to Varro and exclaims, “Varro please listen to me! It is madness to place the infantry so close to the river. The cavalry has no room to maneuver. You may need their support in an emergency.” Varro confidently replies “It’s my turn today understand me? I am in command obey my orders” (1:10:00). Thus, the Roman army proceeds in compliance with Varro’s commands.

Once the battle commences, a Roman cavalry force ambushes the small Carthaginian infantry unit. The infantry retreats according to plan and the Roman army pursues them, believing that the Carthaginians are weak. Hannibal seeing his plan succeeding, slyly states “like rats in a trap” (1:13:35). The fighting begins and the Roman army is soon completely overwhelmed by the Hannibal’s, due to Varro’s faulty battle maneuver. The Roman army signals retreat, but Hannibal orders that “not a single Roman is to leave Cannae” (1:20:50). The Romans are obliterated and while the Carthaginians are surveying the disastrous battlefield, Hannibal finds Sylvia holding a dead Quintilius in her arms.

Back in Rome, realizing their strategy for dealing with Hannibal is ineffective, the Roman Senate appoints Fabius Maximus as proconsul, while bringing him Quintilius’ sword. Looking at the sword, Fabius sternly swears to the senators, “Rome will never submit to a foreign invader. In the words of Hannibal himself when he crossed the Alps, ‘conquer or die’” (1:24:08). The scene then shifts back to Hannibal, who is enjoying a lavish victory feast in Capua, topped off by an arena full of gladiators and games. The festivities are cut short though when Hannibal discovers that Maharbal, who he sent to Carthage to obtain more troops, “has just arrived and is in your tent” (1:27:40). Hannibal and Sylvia rush back to his tent, only to find Maharbal with Hannibal’s wife Danila (Milly Vitale), and son. Feeling completely betrayed and heartbroken, Sylvia steals a horse and miserably departs from the camp. Hannibal angrily demands why Maharbal brought no troops, to which Maharbal replies, “if you had followed my advice, Rome would have been destroyed, and Carthage would not have denied you your request” (1:29:49). Hannibal then swiftly grabs a horse and rushes to catch up with Sylvia.

Hannibal catches up to Sylvia, and during their conversation, a Roman cavalry unit surprises them, and plans to attack them. Seeing that the men are Roman, and still grieving, Sylvia shouts “Stop! Wait! Take me with you I’m Roman!” (1:32:27). Sylvia returns to Rome with cavalry unit and Hannibal never sees Sylvia again. Hannibal goes back to his tent, where he demands that Danila take her son back to Carthage so that he will never “know the meaning of the words hate and revenge” (1:33:49). While Hannibal is ordering Danila to do this, they hear a loud commotion outside the tent. Hannibal soon finds Hasdrubal’s head in his camp. Hannibal had sent him to Italy to wage war and is informed by Mago that a Roman rider threw the head into one of their outposts. Hannibal and his son embrace and mournfully walk away from the atrocity.

In the final scene of the film, Fabius Maximus has arranged for Sylvia to be buried alive for deserting to the Carthaginians. He goes to her cage before the public execution and gives her a vial of poison, showing some mercy towards his niece. While she is being buried, he unhappily looks down at the ring which Hannibal gave her and the scene fades to Hannibal holding the exact same ring. Then, learning that the Romans are attacking his camp, Hannibal prepares for battle. In the final shot of the movie, Hannibal’s austere face is superimposed on the screen with fire and dead Roman soldiers screaming “March!” over and over again, similar to the beginning of the movie on the Alps. However, instead of being merciful, Hannibal is out for revenge (1:39:00).

The main ancient Roman historian who writes about Hannibal and the Second Punic War is Titus Livius (Livy). Livy however, does not write solely on Hannibal and the Second Punic War in his work, but instead focuses more on a collective number of people and events. In his Ab Urbe Condita, Livy wrote not only about the Hannibalic Wars, he also wrote 142 books on the complete history of Rome, ending with the reign of Emperor Augustus. Written around 25 BC using earlier historical texts as assistance, only around 25% of the original Ab Urbe Condita remains. The history of the Hannibalic Wars is told in books 21-30.

Livy writes about the Hannibalic Wars in order to “provide an account of the most momentous war ever fought” (21.1). Therefore, Livy’s main goals are to provide a detailed and accurate account of the events and battles throughout the war, while oscillating between the forces of Hannibal and the senators and consuls of Rome. Because Livy wants to memorialize the Hannibalic Wars, he writes in great detail about every minute topic relevant to the war. During his account of the war, Livy lists the number of soldiers fighting in each battle, including each force’s respective nativity, as well as the many generals on both sides and the men of notable status who were slain during battle. Livy even devotes a whole paragraph during his retelling of the Battle of Cannae to describing what each auxiliary unit in the Carthaginian army carried into battle (22.46). Livy also discusses with great care events going on in Rome simultaneous to the war, and incorporates dialogue among the Roman Senators.

Even though Livy is Roman, he does not falsify Hannibal’s character and perceive him as a barbarian but instead, gives him praise where it is due. For example, while describing the events before the Battle of Trebia, in which Hannibal is in desperate need of supplies, Livy tells how the town of Clastidium held a Roman stockpile of wheat. After capturing the town, Livy states that it “became the granary of the Carthaginians while they remained at the Trebia. So that Hannibal could have a reputation for clemency established right at the start, no harsh treatment was meted to the prisoners from the surrendered garrison” (21.48). Furthermore, Livy is sure to make mention of Hannibal’s allies, in order to show that Hannibal was not only a commander, but a diplomat as well. Livy contributes a large portion of Hannibal’s victories to his alliets, listing all the allied troops who helped turn the tide of the battle. During the initial stages of the Battle of Trebia, Livy states that “when the Numidians struck, Sempronius first led out all of his cavalry” (21.54). Also, Livy uses Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps to credit Hannibal’s diplomacy, as his Gallic auxiliaries “managed to insinuate themselves into conversations with the local mountain men, from whom they differed little in language and customs. Through them Hannibal gained further information that the pass was guarded only by day, and at night all the men slipped away to their own homes” (21.32). Livy understands that Hannibal was a visionary who accomplished great feats in a foreign land, but his ubiquitous mention of Hannibal’s allies helps the reader establish Hannibal as not only a military victor, but as a diplomatic one as well. Without his many foreign allies, Hannibal would have had a much harder time conducting operations in Italy.

There are many historical inaccuracies in the movie. The most noteworthy inaccuracy has to be Hannibal’s perceived friendliness towards the Romans, shown through the fictional character Sylvia. In book 21 of his work, Livy tells the story of how Hannibal’s father Hamilcar “brought Hannibal to the altar and there made him swear to make him himself an enemy of the Roman people at the earliest possible opportunity” (21.1). It is, therefore, impossible to believe that Hannibal would ever talk of peace, as well as show passion towards Sylvia, who is a Roman. It is also unlikely that Hannibal would ever allow the son and niece of Fabius to return to Rome; it is more likely he would use them as leverage to gain information about Rome’s military operations. Also, no character resembling Sylvia is ever mentioned in Livy. Her character was invented solely to function as a love interest and add a more interesting facet to the plot; without Sylvia, the movie would have been a war film with only battles and war preparations contributing to the plot. Also invented, is Hannibal’s romantic personality. In one scene in the movie, Hannibal gives Sylvia a ring so that she could pass into Hannibal’s camp without being harmed. Hannibal tells her that “I wanted to see you, and I hoped you wanted to see me” and then proceeds to kiss her (51:36). Later in the film, Sylvia discovers in Rome that “Hannibal wants you to come to him! He is waiting for you, he loves you!” (57:30). Towards the end of the movie, Hannibal is visited by his wife Danila, another fictional character who only serves to heighten the sexual tension between Hannibal and Sylvia. With these two female characters, the directors Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia and Edgar G. Ulmer completely falsify Hannibal’s romantic and familial entanglements.

Hannibal’s perceived felicity in the film is surely fictitious. In the movie, Hannibal is always smiling and dedicates part of his days towards leisure, particularly seen through his interactions with Sylvia. Hannibal even celebrates his victory at Cannae by hosting a huge luxurious party. Livy writes however that, “his eating and drinking depended on the requirements of nature, not pleasure,” and “the time which he had left from discharging his duties was given to sleep, and it was not brought on by a soft bed or silence” but, “the man’s great virtues were matched by his enormous vices: pitiless cruelty, a treachery worse than Punic, no regard for the truth, and no integrity” (21.4). The Hannibal presented in the last remaining minutes of the movie more accurately matches the one whom Livy writes about. The reason why the movie portrays Hannibal in this way is because it helps enhance his romance with Sylvia. If Hannibal was always sternly focusing on his campaign in the movie, the romance between he and Sylvia would be less believable, as his personality would be more off-putting. However, as stated in Livy, it is extremely unlikely that Hannibal would ever submit himself towards leisure and luxury during his campaigns in Europe.

Like Sylvia, Fabius’ son Quintilius is another made-up character in the movie. Although Fabius did in fact have a son, his name was also Fabius Maximus and Livy writes that Fabius’ son, many years after the Battle of Cannae, was elected to the consulship (24.43). In the movie on the other hand, Quintilius is killed during the Battle of Cannae. Quintilius dies in the movie because it cements the ineffectiveness of the Romans during the initial battles of the Second Punic War. It also underscores that Fabius’ strategy of delay (cunctatio) was the correct way to deal with Hannibal. Since Quintilius and Sylvia were good friends, his death causes Sylvia’s to question her romance and desertion to Hannibal, adding another dynamic to the romantic plotline.

Despite these inaccuracies, the directors do accurately display Hannibal’s diplomacy and usefulness of his allies. In the beginning of the film when Hannibal is crossing the Alps, Rutarius asks Hannibal for the “supremacy of my tribe over all the other tribes in the valley” (16:32). Hannibal grants Rutarius his hegemony and forms an alliance with him, highlighting his unwavering focus on diplomacy. While escorting Sylvia through his encampment, Hannibal makes note of his allies, “my Numidians. And over here is my Libyan cavalry. And over here on my far right are my Spaniards, the greatest horsemen on the continent. And up here are my Carthaginians, the main core of my strength” (31:57). As mentioned in Livy, Hannibal utilizes these auxiliary contingents to secure important military victories for the Carthaginian army. Therefore, the directors understand that Hannibal promoted diplomacy, and allied with many peoples in his quest to invade Rome.

In some respects, the movie correctly depicts the difficulty of crossing the Alps. During the crossing, both in the movie and in Livy, Hannibal’s men “could not keep from falling and, even after losing their balance only slightly, they could not, once in difficulties, keep their footing, so that they would fall over each other, and the pack animals would fall on the men” (21.35). Surprisingly, the movie even shows the difficulties of marching the elephants through the narrow passes of the Alps, as the Carthaginians had melt snow and dig through rock in order to form a wide enough passage for the huge beasts (21.37). Even though the movie correctly displays the harsh natural terrain Hannibal encountered during his time crossing the Alps, it makes no mention of the many Alpine tribes which Livy claims “made predatory raids on the head or the rear of the column” (21.35). I believe that the movie strays away from this facet of Hannibal’s march in order to mold him into a more fearful central hero, common amongst sword-and-sandals movies. Thus, during his march in the film, Hannibal and his army are characterized as an unstoppable force that even the great armies of Rome will have difficulty handling.

There is also a small amount of historical accuracy during the battle scenes in the movie. The directors do a good job at depicting the battle plans of Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae, at which Livy states Hannibal “deployed his battle line, and provoked his enemy with sudden charges from his Numidian troops” (22.44). At the Battle of the Trebia, the film highlights the importance and ferocity of Hannibal’s war elephants, which were a constant threat during the actual battle in 218 BC. The film over-dramatizes their usefulness, though, and attributes to them a large portion of the victory at the Trebia. In actuality it was Hannibal’s auxiliary forces, especially the Numidians who were “to cross the River Trebia, ride up to the gates of the enemy and entice him out to battle by hurling spears” who contributed the most to that victory (21.54). The over-dramatization of these elephants makes Hannibal, as stated before, a more terrifying central character.

The film does an excellent job depicting the constant feud between the two consuls Varro and Aemilius Paulus before the Battle of Cannae. As mentioned in Livy, Varro and Paulus would oscillate each day as the supreme commander of the army, and have endless arguments concerning tactics. Identical to Livy’s description, the movie shows Varro and his followers are “angry and eager to fight” while Paulus “would choose safety over impetuous plans” (22.44, 22.38). Both in the film and in Livy’s work, Varro becomes war-crazed and “without conferring with his colleague in any way, he put up the signal, and led his troops over the river in battle order” (22.45). Although the directors stray away from historical accuracy in their creation of Sylvia and Quintilius, they do a good job accurately depicting Varro and Aemilius, as well as Hannibal’s battle tactics.

Maharbal’s disagreement with Hannibal’s strategy is also historically accurate. After winning Cannae, Livy states that Maharbal wanted to “go ahead with the cavalry – so the Romans will know of our arrival before they are aware of our coming.” However, Hannibal “declared that, while he appreciated Maharbal’s enthusiasm, he would need time to consider his suggestion.” In response to this, Maharbal furiously responds, “you do not know how to use victory!” (22.51). In the movie, Maharbal orders Mago to “explain to me why he [Hannibal] uses every possible reason to avoid combat?” after their victory at Trebia (1:01:20). Maharbal hypothesizes that “If you [Hannibal] had followed my advice, Rome would have been destroyed, and Carthage would not have denied you your request [for more soldiers]” (1:29:49). Unlike Hannibal’s unrealistic personality, Maharbal’s depiction in the movie closely represents his personality in Livy.

Overall, Livy is less concerned with glorifying the Roman name and is more interested in preserving the fascinating history of Rome as accurately and impartially as possible. Even though Livy covers more than 700 years of Rome’s history, he is exceptionally thorough. He has an extreme attention for detail and describes the number of troops each side had, who was in command, and what auxiliary units were utilized particularly well. Despite being a Roman, he is not afraid to praise the admirable qualities of the Carthaginians, or criticize the Romans for their reprehensible ones. In comparison, the directors of Hannibal praise Hannibal for being a great military commander with tons of ambition. However, through the fictional character Sylvia, the movie is more concerned about generating a “war-romance” film in order to retain the attention of the audience. Because of this, the “action scenes can be desultory” and brief, as more attention is given towards Hannibal and Sylvia’s unlikely romance (Hoberman).

Hannibal was directed by the Italian directors Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia and Edgar G. Ulmer and was released in 1959 in Italian under the name Annibale. The movie was not released in the United States until a year later and was not released on DVD until 2004. Funded by Warner Brothers Studios, the movie was shot at Cinecitta Studios in Rome, Italy. Cinecitta studios was founded by Benito Mussolini to promote Italy and fascist ideals through cinema. After the Second World War, Cinecitta Studios was used by many American movie companies because of how cheap it was to film there, the same reason why Warner Brothers chose to use the site. Many other sword-and-sandals movies were also made in Cinecitta Studios besides Hannibal, including Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur (“History of Cinecittà.”). The movie had an estimated four-million-dollar budget (IMDb), which was used to cast “over 4,000 foot-soldiers, 1,500 horsemen, 45 elephants and a vast assortment of war machines” in the Battle of Cannae alone (back of DVD box). Because this movie was filmed in the late 1950s, there were no special effects or use of computer-generated imagery. All of the elephants, horses, and soldiers were present during the shooting of the film and all the battle scenes were shot without special effects. This is the main reason why there are very few on-screen deaths and blood during these scenes.

Victor Mature and Rita Gam, Hannibal and Sylvia respectively, were both American actors and are the two biggest stars of the film. They both recorded their lines in English, as opposed to the other members of the cast, who spoke in Italian. For the English version of the film, all the Italian actors’ lines were dubbed over in English. I believe that the directors of the movie cast Mature and Gam in order to gain more publicity with the larger American audience and generate a larger box-office. However, I personally did not enjoy the acting in this film mainly because the dialogue between the characters felt unrealistic, thus bringing down the plausibility of each character. I also believe that the movie’s inaccuracies, primarily Hannibal and Sylvia’s romance, further exacerbated the weakness of the acting. Because I have prior knowledge of the Second Punic War and have read for this project many sections of Livy’s account, I cringed at most of the scenes in the movie because I know that they simply never happened. A review of the film by Variety Movie Reviews said that, “director Edgar G. Ulmer has not accomplished battle sequences and bloodshed very smoothly or persuasively.” I completely agree with this review, as the battle sequences in this film were extremely dull and implausible. Soldiers were able to flee enemies without any pursuit, sword fights were between two men haphazardly swinging their swords at each other with no intention to kill, there were hardly any on screen deaths, and finally, both of the battle scenes were short (Appendix 3). To put it concisely, “the film gets off to an interesting start in scenes illustrating the difficult and costly crossing of the snowy Alps by Hannibal’s army, but slows down to an elephant’s pace in the romantic passages at the heart of the picture” (Variety).

Hannibal is categorized under the sword-and-sandals, or peplum, genre. This genre consists of movies that incorporate traditional muscleman films into a historically classical setting. The main sword-and-sandals genre primarily focuses on a hero discovering a wrong and setting out to fix it, culminating in a nice, happy ending. However, Hannibal is very different from this style of sword-and-sandals, and falls into the distinct category of sword-and-sandals movies that mainly focus on plot and character development rather than action sequences, similar to the movie Messalina (Young). I think the movie strays away from action sequences because an hour and a half of fighting and military tactics would only draw in a very specific audience, as the movie would feel more like a documentary than a movie. Without the dialogue and character development, the characters of the movie would be dull and lifeless and the audience would in return feel no emotional attachment for any of the characters. The romance aspect in the film allows the audience to develop emotions for both the Carthaginians and the Romans. However, as mentioned earlier, I believe that the movie is ineffective at achieving these goals due to how unrealistic the plot seemed to be. The movie strays away from the traditional sword-and-sandals genre again in the sense that it neglects a main sword-and-sandals theme of fantasy, usually satisfied by the introduction of mythological heroes or gods. However, Hannibal does share themes with the traditional sword-and-sandals style, mainly a central hero (Hannibal) who fights against a villain (Fabius Maximus and Rome). Also, the movie provides a love interest (Sylvia) for the hero, which is common amongst many sword-and-sandals movies.

Because it is predominantly a romance film, the main theme of the movie is that love knows no bounds. Although Hannibal is constantly at war with Rome and Fabius Maximus, Sylvia’s uncle, he nevertheless loves Sylvia and ignores her Roman nationality. Sylvia even abandons Rome and her uncle altogether in order to spend her time with Hannibal. Furthermore, Sylvia stays with Hannibal after the Battle of Cannae after she discovers Quintilius, her lifelong friend, was killed by Hannibal’s army. The scene that does the best job broadcasting this theme is when Hannibal duels Maharbal in a swordfight due to Maharbal’s attempt to kill Sylvia. Even though Maharbal is Hannibal’s cavalry commander and a crucial part of the Carthaginian army, Hannibal puts that all aside when his romance with Sylvia is at stake (59:00-106:00). As mentioned previously, Hannibal even considers peace with Rome due to his infatuation with Sylvia. At the end of the movie, when Hannibal discovers that Sylvia was executed by Fabius, he commands more vigorously and ruthlessly than ever before. As Maharbal states in the movie, Hannibal was controlled by his love for Sylvia (59:00). However, the love between Fabius and Sylvia also contributes to this theme. After Sylvia’s second visit with Hannibal, Fabius spares her from death, because of his love for her. Finally, after Sylvia defects from Hannibal’s camp following Cannae, Fabius, instead of keeping her alive throughout the entire length of her execution, shows mercy final time by giving her a vial of poison. Whether the relationship is between lovers or family members, love in this movie completely defies boundaries.

A smaller yet still present theme in the movie is that patience is the key to success. Throughout the movie, Fabius Maximus was ostracized and heckled because of his strategy to, “tire him, wear him down with skirmishes” (38:50). Fabius never pushed his agenda down the Senate’s throat and calmly waited for the senate to realize their mistakes in actively pursuing battle with Hannibal. However, after losing to Hannibal’s army at Trebia, Transimene, and Cannae, the Roman senate named Fabius proconsul, and gave him control over the Roman army and its operations. However, because the film is over-saturated with love and romance, this theme is rarely present.

A movie which we watched in class which was made around the same time as Hannibal and is also in the sword-and-sandals genre is Spartacus (1960). Both of these movies are in the same subsection of the sword-and-sandals genre but in my opinion, Spartacus is more interesting than Hannibal because it still has a considerable amount of satisfying action sequences in addition to having a good amount of dialogue and plot development. In Hannibal, the romance between Hannibal and Sylvia is at the forefront, with the war being a secondary plotline in the movie. Because of this, the battle scenes in the movie are forced and unsatisfying. In Spartacus, the romance between Spartacus and Virinia is definitely in the background, as the main plotline of the movie focuses more on Spartacus’ revolt against Rome. Unlike Hannibal, Spartacus’s battle scenes were more realistic, as they were filmed outdoors instead of on sets inside a studio. The actors fighting in these battle scenes were much more convincing as well; they did not blindly swing swords at each other, but had some grace in their movements and actions. I also found Spartacus’ romance to be more convincing than Hannibal’s romance because Spartacus and Virinia were both oppressed slaves serving Rome instead of bitter enemies who in theory should hate each other. For these reasons, I was thoroughly intrigued during the entire runtime of Spartacus, but very bored while watching Hannibal, even though the Second Punic War is a subject that I am very interested in.

In my opinion, this film is very weak in its portrayal of Hannibal and the Second Punic War. The battle scenes were atrocious and the soldiers were unintentionally humorous as they blindly swung their swords at each other. If I was shown only these battle scenes without any context, I would think that the movie was a sword-and-sandals parody due to how unrealistic and terribly hysterical the fighting seemed to be. The romance between Hannibal and Sylvia seemed implausible and forced as Livy and other ancient historians note that Hannibal was dedicated to his campaign, had no time for personal luxuries, and would never love let alone mention peace to a Roman. Furthermore, the fictitious characters of Sylvia, Quintilius, and Danila made the movie seem less historically accurate and more fantastical. The only admirable strength in my view is the movie’s portrayal of Hannibal’s determination when crossing the Alps and his diplomacy. Other than those two traits, the movie completely alters Hannibal’s personality, for the worse. When I was initially assigned this paper, I was very excited to watch this movie and learn more about the Second Punic War and Hannibal. However, after watching the movie, I would strongly recommend not watching it because a good portion of it is made-up and the rare scenes that are historically accurate are just plain boring. Although it does a good job in the first twenty minutes depicting Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, the movie does a lackluster once showcasing Hannibal’s campaign in Italy.

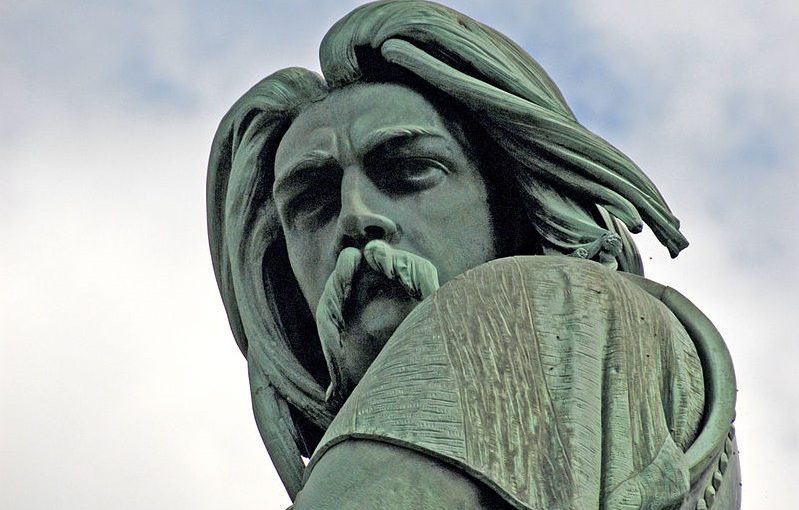

(Header Image: Detail from fresco Hannibal Crossing the Alps. Attributed to Jacopo Ripanda, c. 1510. Palazzo del Campidoglio (Capitoline Museum), Rome. Photograph © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

Bibliography

Hannibal. Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer. 1960. DVD.

“Hannibal.“ IMDb. Accessed May 07, 2016.

“History of Cinecittà.” Studios in Rome. Accessed May 07, 2016.

Hoberman, J. 2004. “Hannibal (Film).” Film Comment 40, no. 6: 78-79. Film & Television Literature Index with Full Text, EBSCOhost. Accessed May 7, 2016.

Livy. Hannibal’s War Books 21-30. trans. Yardley, J. C. and Dexter Hoyos. Oxford: OUP Oxford, 2006.

Variety Staff. 1960. “Hannibal.” Variety Movie Reviews no. 1: 26. Film & Television Literature Index with Full Text, EBSCOhost (accessed May 7, 2016).

Young, Timothy. “The Peplum.” Peplum Guide and Film Reviews at Mondo Esoterica. Accessed May 07, 2016.

Hollywood and History is an on-going series featuring the original work of students in the course Ancient Worlds on Film. Papers have been slightly edited for publication.